Science has come under scrutiny of late. It’s been politicized and trivialized by nitwits who have curtailed serious research by cutting essential funding. Which is not to say science is perfect, but that is also the point: Science requires intense scrutiny to confirm the theories that trigger breakthroughs. One such breakthrough is the scientific fact that a good laugh makes the world a better place.

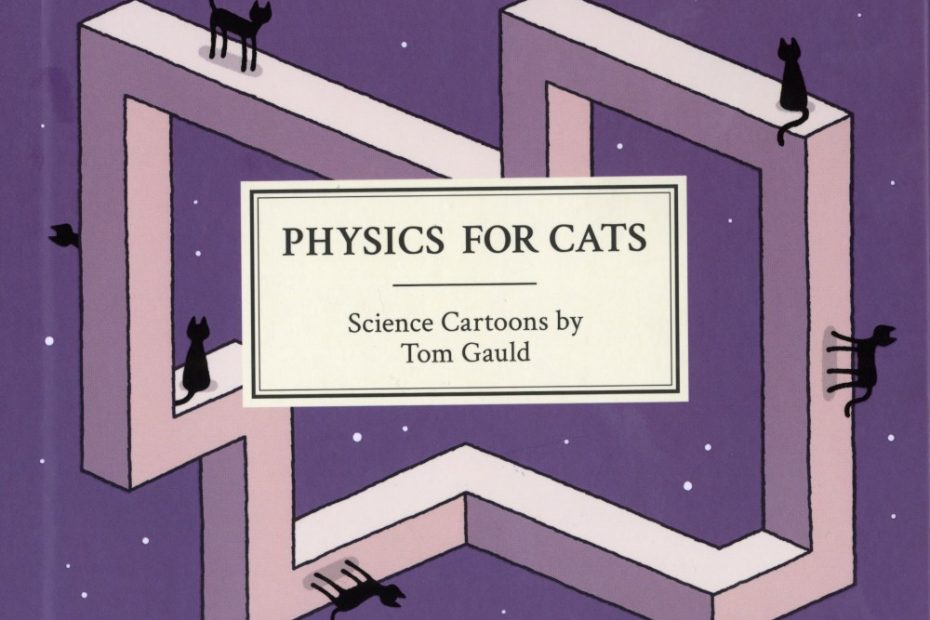

Tom Gauld’s latest collection of single-panel cartoons, Physics for Cats (Drawn & Quarterly), is not about cats—but it aims to make science as fun as them. (And in fact, more so.) His weekly cartoons for the magazine New Scientist target scientific lore, jargon and stereotypes drawn from his skewed understanding of the theoretical and physical. In short, science buffs and skeptics alike will find cartoon joy in Gauld’s comical interpretations of physics, chemistry and biology. Below, he delves beneath the surface of the book, and we are all the better for it.

Is science a field you’ve seriously dabbled in?

I last studied science when I was 17, but I’ve always been an enthusiast for it. My grandfather was a biologist and always had a copy of New Scientist magazine lying around, so it’s been part of my life for a long time. When I started making these weekly cartoons for them, I was worried that the magazine’s scientifically eggheaded readers and writers would not enjoy my amateurish take on their specialism. So I was delighted and relieved with the positive reaction. I hope that my enthusiasm and respect for science come across in the cartoons and make up for any shortcomings in education.

You capture the irony of scientific jargon with a populist way. There are so many scientific/linguistic jokes—what part of your life’s recesses do they come from?

When I started making cartoons, coming from a background in illustration, I leaned more heavily on the visuals. But over time I’m become more comfortable with writing things and enjoy being playful with words. The slight pompousness inherent in jargon makes for good comedy, so I note it down whenever I see something good.

Do you actually understand quantum physics?

I still don’t understand quantum physics on anything more than a superficial level. I’ve done a few cartoons about it. I feel like there would be some great material for cartoons in there if I could develop a better understanding of it, but I read about a page and a half of a book or article about it and my brain glazes over. Still, I hope one day to get there (there being a deep quantum cartoon) …

Your gags and drawings are brilliant pieces of wit—a pleasure to read—but I must say the title of the book does not entirely capture the content, which is much wittier than cat jokes …

Titles are weird. With my one-story books (Goliath, Mooncop, The Little Wooden Robot and the Log Princess), the titles came naturally with the content and felt set in stone without any real effort. But with my collections of short cartoons it is always a struggle to find an attractive title that matches the content. I was more concerned about putting people off with a title that sounded too highbrow, and I hope my regular readers will know what to expect anyway. My main worry is that cat lovers will complain that there are not enough cats in the book. On Amazon UK, it is filed under Animal Sciences › Mammals › Cats & Big Cats.

How have these cartoons been received by the scientists you’ve satirized?

I’ve been really pleased how many scientists have been in touch to ask if they can use my cartoons to illustrate their articles, blogs and even peer-reviewed papers. Over the years of doing science and literary cartoons, I’ve come to realize that the more obscure the content of a cartoon is (a backwater of research, a forgotten novelist), the more excited the people who like that thing will get.

Is this a self-conscious debunking of scientific complexity, or do you naturally think this way?

I’m always trying to look at my subjects in an unusual way, or from an unexpected place. I’m not consciously debunking, or seriously satirizing, just playing around. Though I suppose there is an inevitable simplifying that happens in a small cartoon and contrasts with the complexity of science.

I know it is counterproductive to overanalyze humor, but what triggered the “Rapunzel Experiment” cartoon?

When I was writing my children’s book (The Little Wooden Robot and the Log Princess) I read every Grimm’s fairy tale as well as many others for inspiration. So folk tales were on my mind, and mixing scientific rigor with the magical world seemed like a fun thing to try. Once I realized that length of hair and height of tower could be variables in an experiment, I knew it would make a good cartoon.

Were there any cartoons left on the cutting-room floor?

I make one of these every week for the magazine and about 90% ended up in the book. I edited some out if I felt they hadn’t quite worked, or the theme was better covered in another cartoon. I’ve also realized that it’s useful to have a few replacement cartoons for foreign editions, as a few of the cartoons always turn out to be untranslatable for grammatical or cultural reasons.

What is the next target of your comedy?

I haven’t published a graphic novel for a while, and I really enjoyed creating the other two I made, so when I get back from my book tour I’m going to get to work on that. But I’ll be continuing with my weekly cartoons about science (in New Scientist) and books (in the Guardian) for the foreseeable future.

The post The Daily Heller: Science is a Laughing Matter appeared first on PRINT Magazine.