Lucian Bernhard (1883–1972) is the father of the modern advertising poster—the sachplakat or “object poster,” exemplified by his minimalist Priester Match work. He had moved from near Stuttgart to Berlin to reinvent himself, and also moved freely between New York and Germany. He finally settled in Manhattan in the mid-1920s, and presided over an impressive clientele, including Amoco and White Flash gas, Cats Paw and ExLax.

Bernhard was a modern genius, but this mantle was as much his own invention as the acclaim of others. His earlier life was a bit of a mystery, and he preferred it that way; as renowned as he was, there has never been a proper contemporary monograph covering the full range of his achievements.

Fortunately for graphic design scholars and Bernhard admirers, University of Texas Architecture and Design professor Christopher Long chanced upon some Bernhard material that piqued his curiosity, and he began a four-year research project that has raised and answered some questions about Bernhard’s personal and professional life. He has assembled it all into a highly readable and profusely illustrated historical monograph—the first and only one devoted entirely to this prolific pioneer. Having had access to living family members over 20 years ago, I published some articles and gave talks on Bernhard, so Long asked me to critically read his manuscript. I soon learned what I did not know and was duly impressed by Long’s narrative fluidity and organizational acuity. I hope everyone will be able to read it and luxuriate in its images.

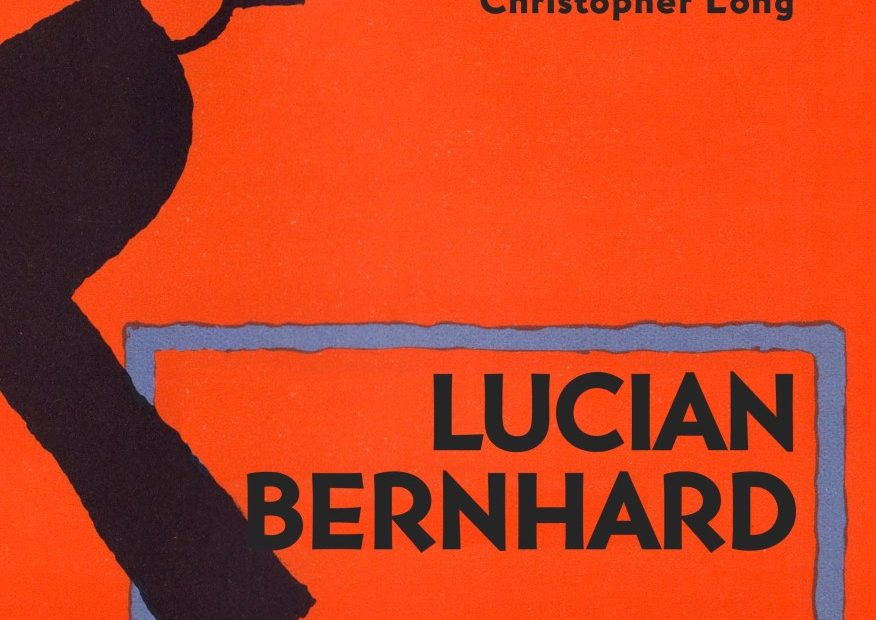

Lucian Bernhard is handsomely designed by Jiří Příhoda and is published by Kant, a leading art and design publisher in the Czech Republic. There is an edition in English, which will be available on Amazon soon. Still, it is too good to keep under wraps a moment longer, so I sample some pages below, along with a brief interview in which Long discusses his invaluable contribution to design studies. (For now, the book can be ordered here.)

I researched Bernhard’s life and work for a long time, but failed to uncover as much information as you have. Where did the majority of this rich discovery come from?

By the time I began writing this book in 2021, the trail had grown very cold. All of Bernhard’s children had died, and I was forced to rely almost exclusively on printed sources. I simply followed the trail from one printed source to the next, looking very carefully for clues in each piece. Because many sources are now digitized, I also searched his name in a very large number of finding aids.

You note throughout the book, as I learned fairly early on, that Bernhard had concocted some of the facts—lord knows how many—about his life, and his sons kept some of those myths going. How did you separate the wheat from the chaff in your research?

To be honest, Bernhard, as I wrote in the book, was a sort of serial fabulist. I discovered very quickly that I could not rely on anything he said or wrote. Instead, I used two strategies: One was to rely on pieces published at the time, and to try as much as possible to confirm every fact. The second strategy, though, is a historian’s trick—I simply asked myself if the story I was uncovering made any sense, and I looked for contradictions or assertions that seemed unlikely. It helps that I have worked extensively on German and American Modernism in this period, so I knew when something did not smell right, so to speak.

Without the benefit that I had of talking to his sons (who worked with him when they finally arrived in New York from Germany) and daughter, the well-known photographer Ruth Bernhard, how did you ferret out the material that you needed to tell his story (and which you accomplished much better than I)?

It was certainly a challenge not to have people I could interview. It is also a problem that the German newspapers, unlike those in Austria, have not been fully digitized. I simply and very doggedly read through every likely source. The primary published sources told the story. To the extent that it was possible, I also relied on archival sources, but that is hit or miss since so many were destroyed in World War II.

What are the original—and perhaps shocking—revelations that you made during the course of your research?

The most surprising discovery for me had to do with the famed Priester poster. Nothing Bernhard had said about its genesis turned out, on closer inspection, to be true. What most shocked me was that it was the product of a long design process, lasting perhaps a decade. It is still a work of absolute genius, but not in the way that Bernhard wanted us to believe.

I was one of those who accepted the origin stories and personal fables at face value. Bernhard’s work took a different turn when he came to live in New York. Do you believe that the American stage was because he no longer had the German plakat style to play off against, or did American advertising just beat him down?

Bernhard was ever the realist. He did what he needed to do in New York to survive, and for him that meant adopting a far more “American” style. But I also think that he recognized that the time for the German Sachplakat had passed, and that he needed to evolve and change with the times. I do not think he ever believed that he had sacrificed something. He just kept moving on.

He designed over 50 typefaces between his German and U.S. work, scores of posters, as well as books, periodicals, logos and brochures. What should be remembered most about Lucian Bernhard?

It is difficult if not impossible to summarize the accomplishments of someone as prolific as Bernhard, but if I had to put it in a single sentence, I would say simply this: He was one of a tiny handful of figures who invented modern graphic design.