How and why did the Yiddish Book Center begin?

It started in the late 1970s with Aaron Lansky, a young graduate student of Yiddish literature in Montreal who couldn’t find the books he needed at McGill University library. He put up notices around the Jewish neighborhood, and soon found himself overwhelmed with people wanting to give him their old books. At that point, he paused his studies and devoted himself to rescuing Yiddish books. First his bedroom filled up, then his parents’ house, and pretty soon the Yiddish Book Center was born. 44 years later, the Center has collected upwards of a million and a half books, digitized an entire literature, transitioned into a broad-based Jewish cultural center, and most recently created the world’s first comprehensive museum of modern Yiddish culture. Along the way, Aaron Lansky wrote a bestseller, picked up a MacArthur ‘Genius Grant’ and he’s still the Center’s President!

Yiddish has long been a vital language, with a stunning legacy that is always on the verge of extinction. I’m amazed by the quantity of Yiddish literature and the avant garde elements of the form. What is your focus in collecting this material?

Yes, the joke is that Yiddish is always dying and always being reborn. Of course, there’s a serious backstory about the language too – the murderous assaults on it, most notably by Hitler and Stalin. American Jews, with rare exceptions, gave up mameloshn – the immigrant mother tongue – willingly as the price of assimilation. As a transnational, stateless and (numerically at least) a small language, Yiddish has always been on the defensive, justifying its worth, and arguing for its place in the pantheon of languages and cultures. And all the while, countless remarkable women and men have left this incredible legacy – tens of thousands of novels, plays, poetry collections, books of reportage and travel writing, memoirs and more. It’s full of surprises and one of those is the sheer range of modernist and avant garde creativity in Yiddish. Our collecting focus is straightforward: we gratefully accept donations of all Yiddish books and everything else related to Yiddish print culture. Packages and boxes arrive unsolicited in the mail almost every day. We rarely know in advance what we’ll find. It might be a single worn Yiddish cookbook with food stains, a treasured collection of popular sheet music, or an important scholar’s library of rare books. We don’t advertise and we never buy books; things just find their way to us.

Is there a reason for locating the Yiddish Book Center in Amherst, Mass., away from the one time center of Yiddish culture, New York City?

Yes, it’s here because Aaron Lansky had been a student at Hampshire College. When he was looking to build a permanent home for the Center, the College offered this beautiful piece of land amidst an apple orchard on the corner of the campus. The result is a building that would never have been possible in the real estate market of New York – a spectacular wooden temple to Yiddish, suffused with light and built with old-world craftsmanship. It was designed by our visionary architect Allen Moore in a style that’s been dubbed ‘heymish modern’, or perhaps that should be moderne.

What is the scope of your collection in terms of geographic location? Do you acquire from all the hot spots of Yiddish activity?

That’s one of the endlessly fascinating parts of our work – the surprising origins and round-the-world journeys of the books and journals that arrive on our doorstep. It’s a never-ending lesson in Jewish cultural geography. At this point, most books are mailed from the USA and Canada, often from the children and grandchildren of the original owners and readers. But the books originate from all the major centers of Yiddish publishing: New York, Chicago, Montreal, Warsaw, Paris, Vilnius, Buenos Aires, Tel Aviv and elsewhere. Then there are any number of minor centers, such as Denver, Winnipeg, Mexico City, Munich, Vienna, and Shanghai. On top of that, our books have backstories: you find booksellers’ labels, public library cards with full borrowing histories, and stamps from amateur Yiddish literary or drama groups. People leave other marks: heartfelt inscriptions or kids’ graffiti. One schoolbook from the 1930s has a careful color sketch of a hammer and sickle. My personal favorite: a volume of anarchist writings, presented as a birthday gift in 1912 from a father to his daughter to guide her on her life’s journey.

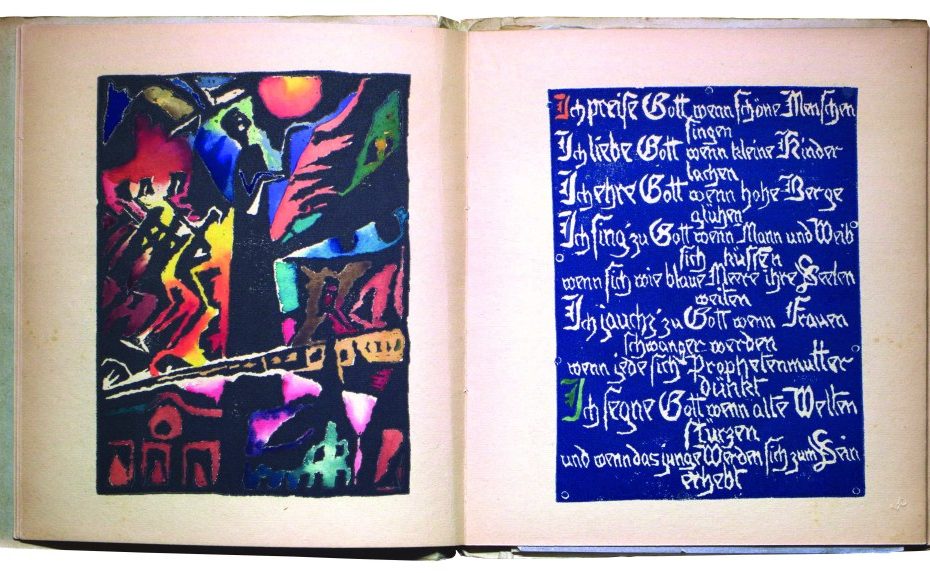

In terms of design, I know of some avant gardists, like El Lissitzky, who engaged in Yiddish works. Who are the most important / influential designers in your collection?

Yiddish modernism bursts onto the scene in the aftermath of the 1914-18 war – a time when worlds collide as never before. El Lissitzky is a key pioneer of this revolutionary moment in Russian Jewish art and design – a breathtaking mash-up of Jewish folklore and tradition with the latest modern art -isms. Joseph Chaikov, Sarah Shor, and Mark Epshteyn are others who work in this vein, all brilliant Soviet Jewish illustrators. Marc Chagall, Issachar Ber Ryback, Boris Aronson, and Jankel Adler are cosmopolitan nomads with a different trajectory: all work as avant garde illustrators and artists in Yiddish, but travel widely and are also active in Russian, Ukrainian, German, French, and American theater and design. Henryk Berlewi in Poland is another fascinating figure – a pioneer of abstraction but also a draughtsman who can hold a line as well as Picasso. In America, radical politics, the urban metropolis, and Yiddish print culture define the work of artists like Isaac Friedlander, William Gropper, and Louis Lozowick, all of whom work even-handedly across English and Yiddish print culture. And then there’s Zuni Maud and Yosl Cutler, a madcap pair of communist-aligned bohemians with a folkloric and surrealist sensibility. They collaborate as artists, book illustrators, Yiddish newspaper cartoonists, costume and stage designers, and political puppeteers. We probably have hundreds of books and magazines with their work. Our new exhibition has finally given us a chance to put work by many of these artists on display within a broader cultural context.

Hebrew alphabets were sold through various typographic houses and foundries — often called “Oriental” — how much of this typefounding tradition is preserved in the collection?

Over the years dozens of trays of Yiddish (ie Hebrew-alphabet) wood and metal type have been donated to us, many by former typesetters and printers. Almost certainly, we now have one of the biggest such collections in the world. Some of them are apparently unique surviving fonts. We also have some exquisite oversize wooden letters, curvaceous and honey-colored, that would have printed old Yiddish theater poster titles. And then there’s our 1918 Yiddish linotype, now mute, but which saw seventy years of cacophonous service. It’s at the heart of our new exhibition, Yiddish: A Global Culture, and helps to tell the story of its place of origin, the storied Jewish Daily Forward newspaper.

What is the status of the collection now? Are scholars welcome? Is there an online presence?

Scholars, students, the culturally curious, young and old, everyone is welcome! We have a wealth of English-language content on our website including a huge oral history video archive, print features, translations, and blogs. Our Steven Spielberg Digital Yiddish Library launched in 2009, making Yiddish probably the world’s most accessible, free-to-access corpus of any literature. A few years later, we developed state of the art OCR software to make it fully searchable. Here at the Center, we have the new core exhibition, temporary exhibits, tens of thousands of used books to browse and purchase, and special collections that scholars can visit by appointment.

And what kind of scholarship is going on at this point in history?

How long have you got? Seriously, it’s such an exciting time to be in this field. In the Americas, as well as in Europe and Israel, you find brilliant scholars of Yiddish squeezed into every corner of academia: not just in Jewish studies but in German or Slavic or Theater studies as well as English and Comparative Literature. And since Yiddish culture was created and consumed in multilingual, multicultural societies, that broad grounding across disciplines and languages perfectly reflects its subject. Some hot topics? Women writers, popular literature, yeshiva and Hasidic Yiddish today, gender, queer studies, Yiddish writing about race and difference, the emergence of a mass readership, Yiddish in Argentina and Israel, children’s literature, pogroms and mass violence, radical movements, Yiddish and Hebrew as one bilingual modern literature, klezmer and Yiddish operetta studies, and on and on. The field of Yiddish might be seen as marginal, but it’s bursting with incredibly smart and sophisticated scholars and practitioners. Best of all, it’s a deep wellspring of a field; there’s so much still to explore, to be inspired by, and to learn from.