I now reside in the silence of my tribe willing to forsake me for telling the truth about something that happened to our forebears almost a century ago, long before any of us were born. Was it necessary to tell the story of my grandmother’s leaving? It was vital to the book. It was vital to my understanding of who my father was, and who I became. And after a decade, I have finally come to this place of peace: the perceived betrayal wasn’t in my writing about it; it was in my finding clarity and humanity in this act that had brought with it so much shame for so long. ~ Elissa Altman, 2024

In 2013, I had been writing my narrative food blog, Poor Man’s Feast (1.0) for five years. It had been a finalist for several James Beard Awards and, in 2012, won in its category before being a finalist again in 2014 and 2015. A year earlier, in 2011, I had been contracted by Chronicle Books — specifically, the amazing Leigh Haber, who went on to become the books editor for Oprah — to write my first memoir, which was meant to be loosely connected to the blog (which turned out to be less about food, and more about family, love, nurturing, grief, and change).

If you’re a new writer and you find yourself caught up in it, I have one suggestion: put your head down and get back to work.

A decade later, we have a new permutation of Poor Man’s Feast on Substack, and it is, by design, not a food Substack, although it does often contain recipes. In writing it, I try to reach a place that lives at the intersection of sustenance, nature, and what it means to live a creative life. I’m not particularly interested in writing about politics here, or the things that divide us, although I do often write about the environment, and that cannot help but be political. I’m also not interested in who is competing with whom in the writing community: it’s a fact of my work, sadly, and often an unbelievably vicious and distracting one, but I think that it results in a lot of time spent away from the craft itself, and ultimately dilutes it. All I can say is Why. If you’re a new writer and you find yourself caught up in it, I have one suggestion: put your head down and get back to work.

Anyway, years ago, I described Poor Man’s Feast-the-blog like this:

Remember that scene at the beginning of the movie Il Postino, when the postman, played by Massimo Troisi, is sitting down with his father, slurping soup, mumbling back and forth in a way that is so authentic that you feel like an interloper, and you want to lean forward and say What? What did you say? They’re slurping and eating, mumbling, talking. All around him is quiet mundanity and beauty and love, and then, poetry, in the form of Pablo Neruda. So when I was asked early on, this was the best way for me to describe a poor man’s feast: the mundanity of love and a simple life, thoughtful words, economy of language, the plainness of honest food, affection, proximity to the sea, poetry, music, family, friends, community, human frailty, forgiveness. This is sustenance. It may be an oversimplification of a modern human life, with its responsibilities and its bills and insurances and jobs and illnesses and complications, but nonetheless, we know sustenance when we see it.

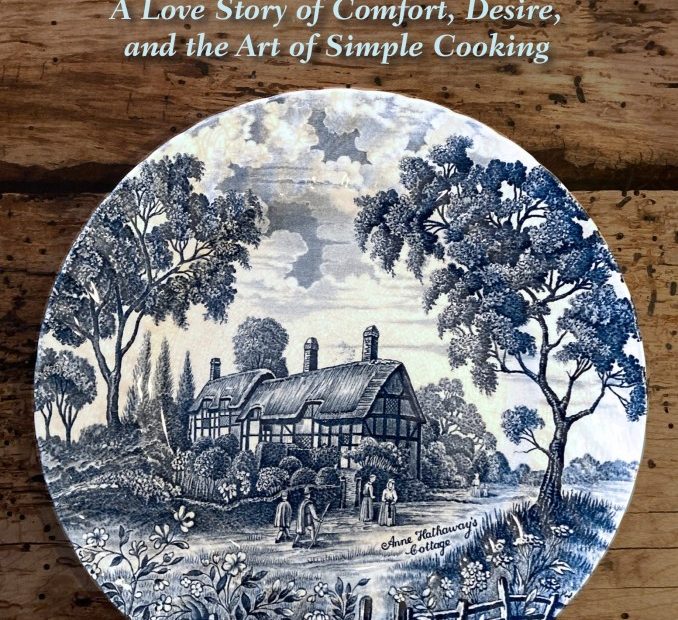

New 10th Anniversary Edition of Poor Man’s Feast

A decade ago, when I began writing the memoir, I knew that love had to be at the core of the narrative. Familial love, romantic love, filial love, platonic love. I had zero interest in the maudlin or the saccharine. It was meant to be a love story about two adult women at the midway point of their lives — both only children, both prone to what Grace Paley called melancholia, both the primary caregivers for two very difficult mothers — falling in love, making the daily decisions that form, nurture, and shape a life. There were backstories: my complicated relationship with my beloved father, who died in 2002 a week after he was in a car accident; my close connection to my paternal family who were like the siblings I didn’t have; my father’s lifelong and relentless search for nurturing and security; the abandonment by my grandmother of my father and aunt when they were young children, and her eventual return; and the profound need to sustain ourselves in whatever form that sustenance comes. (Also, the publisher wanted recipes, so: recipes.)

Abandonment begot abandonment; with trauma gone unhealed, it almost always does.

Right before publication, I lost my editor and the publisher announced that they weren’t going to be doing narrative non-fiction anymore, so the publicity was minimal and the print quantities tiny. A few months later, I made the discovery that no memoirist ever wants to make: the most vital thread in the story, around which the entire narrative was wrapped— the reason why my father was so connected to the table, and to the act of nurturing; this is the thing that shaped my world view — had been common, nightly dinnertime conversation in my home until I went off to college. But the same story — that my grandmother had left her family for a brief time in the late 1920s; she ultimately returned and lived a life of love and doting on her children — was kept a secret from most of my paternal cousins. When the book came out, it was believed that I had let fly with a horrible family secret that was never, in my home, a secret. Words like betrayal and cruelty were thrown around, and I was excised from a large swath of the family. Abandonment begot abandonment; with trauma gone unhealed, it almost always does.

The book came out in paperback in 2015. I didn’t publicly share this story because I was still working through the loss of my father, and now I was working through the grief of losing most of my family as well. For the next several years, I watched family functions unfold on social media; birthday parties, anniversaries, vacations. I watched my younger cousins grow up on Facebook, as though I were hiding behind shrubbery. Well-meaning people connected to us began to send me photos of family celebrations, thinking they’d make me feel better; in fact, they translated to They’re getting on just fine without you. I began to anesthetize myself in any way I could, often suicidally; a therapist referred to it as Your own personal Holocaust: you woke up one morning, and everyone was gone. My marriage began to suffer when my mother-in-law was dying of congestive heart failure and I was so enmeshed with the loss of my own family that I couldn’t be there for her.

Poor Man’s Feast, a simple, linear love story about two very different women who fall in love at midlife had, in exactly eight sentences two thirds of the way through the book, upended my world.

And yet: I write memoir. I teach memoir. It is the form I’m most drawn to. It’s what I do, and it’s who I am as a writer. What came as a result from this simple book about love? Loss. Anguish. But also, profound, unimaginable clarity. And confirmation that no two people will ever tell the same story the same way; if you are a writer of memoir or you want to be one, you have to accept the fact that there will be unexpected and unpredictable fallout. You won’t be able to control that fallout, try as you might. And at the end of the day, that fallout — it may not be as extreme as what happened to me — very likely has its roots in something other than the story you may have told in your book.

Since Poor Man’s Feast first appeared in 2013, I have written extensively about permission and story ownership — what it means and what it doesn’t. I teach memoir workshops everywhere from Fine Arts Work Center to Maine Writers and Publishers Alliance and beyond, at the university level; I lead an ongoing private masterclass now entering its third year, and I’m a regular visiting writer. Everywhere I teach, this is the elephant in the room: who am I to write my story? My next book, On Permission, is coming out in late 2024, and it mines the answers to these questions: do we have the right to tell our own stories if they bump up against other lives? (Yes; none of us lives in a vacuum. We all bump up against each other. But, there are moral considerations.) Are secrets truly secrets if nobody bothers to tell us they are? (No; if you do not know that something is a secret and you write about it, you cannot be held responsible. If you are, there’s something else going on.) What does shame do to art-making? (It destroys it.) If you relate a story about something that you witnessed firsthand, and a family member or friend who was not present contradicts you based on hearsay — essentially they’re calling you a liar — who is right and who is wrong? (Only the person who was present can attest to it; the rest is the game of telephone.) What is truth, and what is fact? (They are not the same.)

If you are a writer of memoir or you want to be one, you have to accept the fact that there will be unexpected and unpredictable fallout.

It is also human nature to insist that one is right— we are very invested in being right; just look at politics —but, as I tell all of my students, you could put five grown siblings around a dinner table and ask them Hey could you tell me what happened on Christmas in 1975 when your dad got drunk on the Jim Beam and all of them will tell you different versions including one who will say Dad didn’t drink. And each one of those versions is a truth belonging to its owner.

A cautionary tale that I share with all of my students: the act of writing memoir is heavy with responsibility. It is not to be done blithely. It is important to get things right or as right as they can be, and it is just as important to be true to one’s own life, situation, and memory. Memoir is not, to quote Mary Karr, a work of history; it’s a work of memory. And my memory is different from your memory. What we are not allowed to do, ever, is fabricate. That’s not memoir; that’s fiction.

So here we are, ten years later, and a new edition of Poor Man’s Feast is now available’; I also narrate the audio, as I did for Motherland, and as I did for the reissue of my second book, Treyf.

My world since the publication of the first edition has changed profoundly; everything in my writing and personal life has been altered, from my understanding of the vagaries of storytelling and family myth to epigenetic trauma, obligation, and the tentacles of shame. I am used to it, my father’s silence, and his silence is a burning in which I reside, writes Mark Doty in his essay Return to Sender. In the writing of my own story a decade ago, I now reside in the silence of my family willing to forsake me for telling the truth about something that happened to our forebears almost a century ago, long before any of us were born. Was it necessary to tell the story of my grandmother’s leaving? It was vital to the book. It was vital to my understanding of who my father was, and who I became. And after a decade, I have come to this place of peace: the perceived betrayal wasn’t in my writing about it; it was in my finding clarity and humanity in this act that had brought with it so much shame for so long.

And it is humanity — the reason why we write memoir at all — that is, as Marilynne Robinson writes, a privilege.

This post was originally published on Elissa Altman’s blog Poor Man’s Feast, The James Beard Award-winning journal about the intersection of food, spirit, and the families that drive you crazy. Read more on her Substack, or keep up with her archives here.

Image courtesy of the author.