Architects with creative flair are needed to overcome stigmas around social housing, urges Polish-American architect Daniel Libeskind in this Social Housing Revival interview.

“More good architects should get involved in social housing,” Libeskind told Dezeen. “We need creativity to overcome the social-housing stigma and we need architects who can invent new ways to create housing that is decent, has dignity, is beautiful and sustainable within the budgets allowed.”

“If you’re an architect that engages with the issue of housing in a creative way, then you’re a much-needed solution to a problem.”

Allan & Geraldine Rosenberg Residences is a social-housing block in New York designed by Daniel Libeskind

Libeskind, whose eponymous studio completed a social housing project in New York last year, believes that creating better quality low-cost housing is one of the most urgent issues facing the world today.

He argued that many contemporary social-housing projects are designed by copying failed examples from the past that do not adequately meet people’s needs.

“Too much of what we call ‘social housing’ is just formulaic from another era,” he said. “It’s popped out automatically in a typology that isn’t very close to the human spirit.”

Because of this habit of regurgitating a perceived typology of social housing, some architects are hesitant to attach themselves to the projects, Libeskind claims.

“I think the minute you say those words ‘social housing’ people think, ‘I don’t want to be involved in this, let somebody else do it’,” he suggested.

“And yet it’s the most pressing problem: to create better housing for people to lift the neighbourhoods that really need help to become better and safer. It’s key to the survival of cities and it’s not only in one place – it’s all over the world.”

“A wonderful privilege” to live in social housing

Now one of America’s most prominent architects, Libeskind’s views on social housing stem from his experience living in a New York City housing cooperative in the late 1950s and early 1960s when he was a teenager.

After leaving his birth country, Poland, in 1957, Libeskind and his family moved to Israel and then to New York in 1959, where they lived in the Amalgamated Housing Cooperative in the Bronx.

Founded in 1927 by the Amalgamated Clothing Workers union, it was the first housing development to be built in the US under limited equity rules – a home-ownership model where residents purchase a share in the development, granting them the right to occupy one of the housing units.

Libeskind described how the public and social gathering space in the Bronx cooperative gave him a positive view of social housing and informed his approach to design.

“I always say, what a wonderful privilege it was to live there,” he said. “It taught me a lot.”

“The housing was walk-up apartments with no air conditioning, but it had a social life with nice public spaces with green trees where people could congregate on hot evenings, rooms for lectures, and places where people would gather together for a performance.”

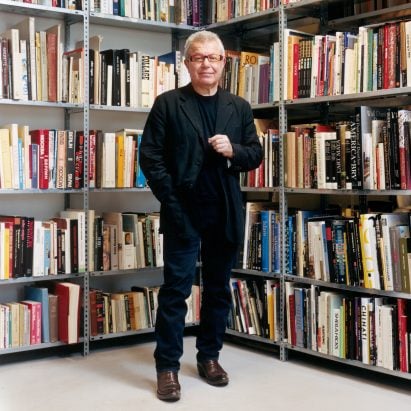

Libeskind’s experience living in social housing influenced how he designs his projects

“It had kind of a sense of culture to it,” Libeskind continued. “It wasn’t windows and walls and staircases, it had a sense of a community and that really had a big impact on my view of the beauty of social housing.”

Libeskind completed a social housing project in Long Island, New York, last year and has another under construction in Brooklyn. The architect explained that he designed these projects by “thinking about the people first”.

“People need security, a beautiful place to gather together, and a place with a nice view even if their apartment is very small,” Libeskind explained. “They need to have a connection to the people living on their floor and to people on the street.”

“It all starts with people first and then thinking about how to shape the space according to the programmes.”

Affordable housing “the centre of what we have to address”

Authorities in New York City are starting to contemplate social housing as aesthetically considered buildings for the first time in decades, Libeskind claims.

“The New York City public-housing authority is beginning to think about a new generation of social housing that would be something beautiful for people,” he said.

“I think that’s a change of perspective because for so many decades there was nothing done on the topic that was inspiring.”

He believes the social housing under development today in New York is a welcome departure from the deteriorating and stigmatised subsidised housing built for low-income households in the past, colloquially known as “the projects”.

Many of these housing projects were built to poor quality standards and disconnected from the city, meaning they succumbed to class and racial segregation.

“There has been improvement in New York where people are trying to create social housing that is no longer what they used to call ‘the projects’, and are beginning to realise that to create a great city you need to concentrate on affordable housing,” Libeskind said.

“People are realising that affordable housing is no longer just a footnote,” he continued.

“It is the centre of what we have to address as architects, authorities, lawmakers and politicians because, without it, we don’t have good cities, we will have cities that are very segregated with ghettos of the rich and ghettos of the poor.”

To Libeskind, the good social housing can improve people’s quality of life and influence how they treat their environment, which impacts both the residents and people living in the wider neighbourhood and city.

Libeskind believes more input from architects is needed to overcome stigmas tied to social housing

“Design has a lot to do with making housing a place that people really want to live and take care of,” he said.

“By creating high-quality housing that people can afford to live in, you can address not just one of the hundreds of people that you’re building the building for, but the entire neighbourhood will change,” he continued.

“The character of the street, safety and sense of belonging in the neighbourhood – it’s a synergy of all these dimensions that comes together when one really thinks of investing in social housing.”

Although architects have a part to play in improving the state of public housing in the US, Libeskind acknowledged that the main responsibility lies with government authorities and people commissioning the projects.

“It’s not just an architectural problem,” he said. “Architects have a kind of limited role in it and really, it’s a problem of politics and law.”

“We have to encourage politicians to take a different stance when it comes to social housing, not just a nod of the head to some buildings being built, but understand that this is a central feature of our time – we have to provide beautiful housing at affordable prices and create integrated neighbourhoods that are linked to the city.”

The top portrait of Libeskind is by Stefan Ruiz. The photography of the New York social housing block is by Inessa Binenbaum.

Illustration by Jack Bedford

Social Housing Revival

This article is part of Dezeen’s Social Housing Revival series exploring the new wave of quality social housing being built around the world, and asking whether a return to social house-building at scale can help solve affordability issues and homelessness in our major cities.

The post “More good architects should get involved in social housing” says Daniel Libeskind appeared first on Dezeen.