Designers value script and states are reinstating cursive’s education, yet Gen-Z can’t read it and brands are straying from it. We explore.

Whether we realize it or not, everyone has a connection to cursive. For me, at least, my cursive story began in fourth grade. It was part of the curriculum, and we spent one class every day learning how to write in cursive.

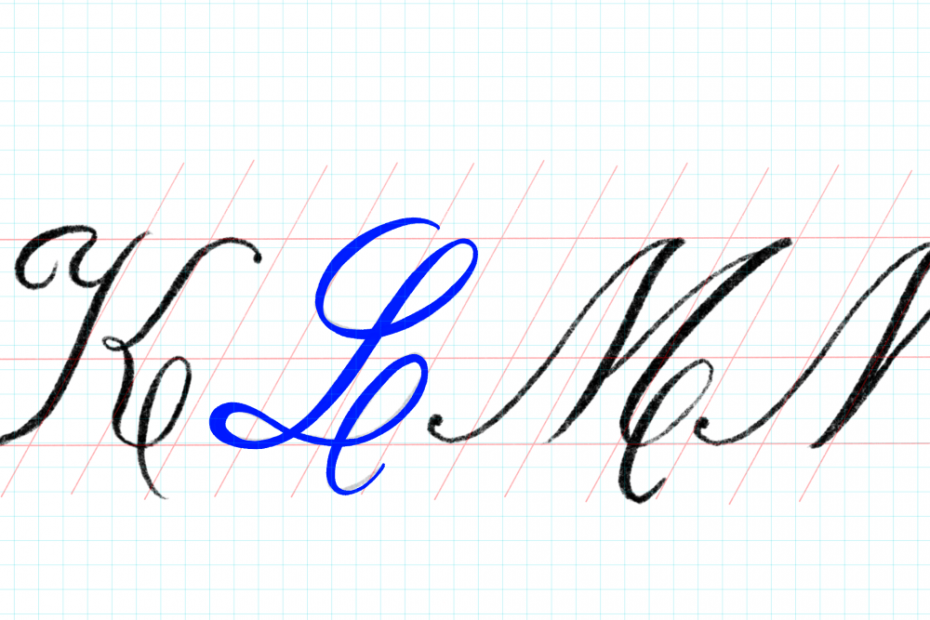

At the time, I didn’t understand it; it was a class I dreaded because, like math, I didn’t understand the point. Now, as an adult who’s made a hobby out of calligraphy, my workbook from elementary school with dashed, traceable letters is a visual ingrained in my memory. But at ten years old, with computers becoming increasingly portable, my classmates and I didn’t understand the concept. We rolled our eyes as we moved through learning the alphabet, wondering why we couldn’t just go to our computer class.

By the time we got to the letter “x,” all motivation had been lost. Our teachers continuously told us about the importance of cursive–that it was not only a more mature way to write, but it would enable us to read historical papers and letters from our ancestors one day. As a class, we collectively groaned.

© Vicarel Studios

Eventually, the classroom began to phase cursive out, likely seen as a waste of resources and funds. With the rise in technology, educators found, with their limited time, that teaching students technology outweighed the importance of the curly-cue letters. In 2010, the Common Core standards, also known as established benchmarks for reading and math, became more widely adopted, and they no longer required states to teach cursive, leaving the decision up to individual states and districts. With this shift in the standards, 45 states chose not to teach cursive, leaving hundreds of thousands of students without the skillset.

“Writing in cursive or in script is part of history, and it feels like a weird thing to just say, ‘this isn’t important anymore,” shares Adam Vicarel, Principal and Creative Director of Vicarel Studios. “It’s like saying, yeah, the War of 1812 happened a long time ago, so let’s just stop talking about it.”

He continues, “Everything is informed by the past, and the best way to take action is to be informed by what happened before you. To stop practicing cursive or learning cursive is strange.” Vicarel feels it’s an extreme oversight to think that no one cares about it.

(© Vicarel Studios)

Kelsey Voltz-Poremba, assistant professor of occupational therapy at the University of Pittsburgh, told BBC that children can learn and replicate cursive more easily. “When handwriting is more autonomous for a child, it allows them to put more cognitive energy towards more advanced visual-motor skills and have better learning outcomes,” she told the publication. Cursive has proven to have a range of benefits for students. Even beyond advancing their visual-motor skills, learning cursive has been demonstrated to help children with dyslexia. According to PBS, “For those with dyslexia, cursive handwriting can be an integral part of becoming a more successful student.”

As a sign of progress, in 2014, a bill in Tennessee required that cursive be a mandatory subject in grades two through four. Then, in 2019, Alabama, Louisiana, Arkansas, Texas, Virginia, Florida, and North Carolina followed suit and required similar measures.

Most recently, California and New Hampshire have reintroduced the mandatory teaching of cursive. According to the LA Times, “Even before the new law took effect on January 1 [2024], cursive was a California learning goal in grades three and four, but the state and school districts had not enforced its teaching or tested to see whether students had mastered it. The law states that handwriting instruction for grades one to six includes writing ‘in cursive or joined italics in the appropriate grade levels.”

And while some states are introducing mandatory cursive lessons, they are not required to be enforced or funded. Without a Common Core standardization, schools do not have much motivation to enforce the education. Hopefully, other states will follow suit, with California and New Hampshire recently adopting the curriculum.

For now, though, we’re existing in an interesting space where current designers are creating for people who weren’t taught cursive in school. We’re seeing more and more heritage brands redesign their well-known cursive logos to simple, sans-serif typography. From Eddie Bauer and Johnson and Johnson, the logos are getting less and less curly. But as brands leave behind the cursive designs, they leave behind the human touch.

Phil Garnham, Executive Creative Director at Monotype UK, states, “There’s a tactility to cursive, the kind of warmth that is reminiscent of nostalgia. I think there’s a human crafty element to it that is important for brands.” Essentially, cursive has the innate ability to allow brands to showcase a more humanistic side.

(© Vicarel Studios work for The Wild)

I’m also completely depressed by the kind of sans-serif of digital modernism of the state we’re in. …We’re missing emotive design. That’s why cursive is so appealing to me at the moment. There’s a great opportunity. [Cursive] is almost like a gateway to uncovering new ideas and new potential.”

Phil Garnaham, Monotype

While the humanistic touch in design is vital for consumers (and people) to feel a visceral connection, Vicarel has been asked by brand clients to refrain from using cursive because their target demographic can’t read it. “We’ve done projects where the agency gave us all the creative direction and then specifically said, ‘Don’t explore scripts because GenZ is our target audience, and they can’t read script,’” he notes.

“It’s not only sad to acknowledge that that generation already struggles to read it,” says Vicarel. “High-end fashion brands are moving away from using ornate serifs, and now they’re all sans-serif. It just takes so much character and like life and personality out of whatever it is that you’re creating.”

Garnham agrees, “I’m also completely depressed by the kind of sans-serif of digital modernism of the state we’re in. We’re not seeing any bravery in brand design at all right now. There’s an obsession that you can just take any sans-serif and apply some quirky character or some subtle shift on it and put the same color palettes in. We’re missing emotive design. That’s why cursive is so appealing to me at the moment. There’s a great opportunity. [Cursive] is almost like a gateway to uncovering new ideas and new potential.”

Image courtesy Vicarel Studios

But while some designers and brands are moving away from cursive in fear that future consumers or brand loyalists won’t be able to read their designs, others are leaning in. Vicarel is one of those designers, creating a typeface inspired by a third-grader’s handwriting practice book that he purchased on a visit to Portugal. “There are enough letterforms in the book to create a typeface. We are able to digitize all of the letters very easily, so, quite literally, the process would be scanning it in. It’s possible that we can take the primary structure of all the letters and almost leave them as is,” he notes. “We will probably make certain adjustments on some letters, but in particular, the accent stroke because it will have to be the same on every single character to be sure that they meet together nicely.”

Now that California and New Hampshire require students to be taught cursive, the design pendulum will hopefully swing back in the opposite direction. If younger generations can confidently read script typefaces, designers and brands won’t be afraid to use them.

The design world is cyclical, but never before have we seen a cycle so obvious in typography. It’s fascinating to break down the importance of typographical education, especially if it’s in the form of teaching children how to write. The cognitive benefits are there, but so are the humanistic, emotive design benefits. Technology is essential, yes, but there’s nothing quite as dynamic as the human touch.