For Ishan Koshla, the impetus to start Typecraft came about after he moved back to India in 2008, following a 13-year stay in the United States. He noticed mainstream graphic design in India looked, “or tried to look,” like design in the U.S. or Europe, and felt designers in India who were trained in a Eurocentric methodology had completely turned away from the depth of visual languages and cultural heritage of South Asia.

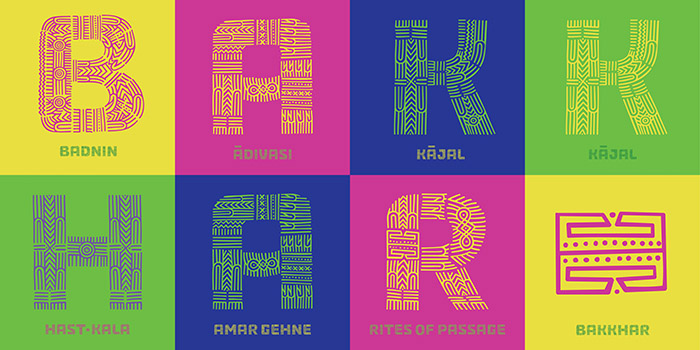

The Typecraft Initiative Trust launched in 2011 to engender avenues for greater exchange between urban graphic designers and rural craftspeople. It started as a way to celebrate the rich handmade crafts (and tribal arts) of South Asia in the digital avatar of a typeface.

Here, Koshla—a graduate of SVA MFA Design, where his thesis involved the creation of a design school in India—talks her about the interaction between craftspeople and type.

Why did you start Typecraft?

The idea of making fonts was chosen because of various reasons. Firstly, when I moved back to India from the States in 2008, graphic design to be seemed disconnected from any sort of Indian sensibility—whether literally in terms of the rich visual culture of the country, or metaphorically in terms of what it meant to be Indian in that zeitgeist. I saw this as an opportunity to bring something deeper than kitsch Bollywood or truck art that most people outside India thought Indian graphic design was about. Secondly, returning to my country of origin for the first time since becoming a designer made me want to learn more about its people—the “everyday” Indian in urban centers like Delhi, but also the people of village and small-town India. I traveled across the country, and I would use this as a way to explore new ways of working between a Western-educated designer such as myself and people who work on the street, such as carpenters, metalsmiths and even henna temporary tattoo art.

Some of the work I did was exploratory and got shown at art exhibitions, while others got used in numerous book covers that I used to design in those days. Thirdly, I launched Typecraft because I wanted to work with something that has a functional basis that can be used by people anywhere in the world—to build greater understanding and empathy between people across the globe. Apart from fonts, we have also worked on short digital animations for a village school website. The artworks of the animation are based on a folk art of Mithila that is usually done on village mud walls and floors during festivals and marriages. Finally, and most importantly, I wanted the craftspeople and tribal artists themselves to realize the true value, relevance and significance of their culture and its transformative qualities even in the digital and AI-driven world we live in today! This is especially [important] as many of [them] come from poor backgrounds that don’t always value their own tradition, art and belief systems, and who aspire to migrate to large cities or even to the West.

The creation of typefaces/fonts from a folk craft or indigenous tribal art (these terms will henceforth be used interchangeably) is unprecedented (to my knowledge). Lettering from craft has been done before, but never before had a full-fledged functioning font. And while we started out with Latin script letters, we have diversified to Devanagari (Indic scripts) and Arabic. However, I have to stress the fact that the latter is way more complex than the Latin typefaces due to the extremely large number of nodes and character sets, hence the heaviness of the font file!

The idea—for this interaction between these disparate groups of people (urban and rural) that seldom talk to each other, let alone work with each other—came to me while working on my MFA Design thesis (at the School of Visual Arts in 2004–2005) that looked at the creation of a design school in India that combined rural and urban visual languages but also would bring students from across India’s diverse landscape under one roof. Termed DeSI—or Design School India, it translates as “one’s own country” and also forms the first four letters of the word design. The thesis emphasized the need for design students in a country such as India to be equipped to address sociocultural needs such as illiteracy, while collaborating with the rich craft and vernacular art (including Bollywood and truck art) communities of South Asia without being patronizing (as many designers tend to be). Students graduating from even the most expensive D school today are extremely ill-equipped and insensitive to the politics at work when working with craftspeople, and design pedagogy remains highly colonized (and frozen) in countries such as India.

Typecraft started where DeSI left off—to see things from the perspective of the craftsperson, and the importance of collaborating with them and using design thinking workshops as a rare chance for makers to be paid to experiment, fail and learn as they usually are given tasks, and sadly many times the final design is just implemented by outsiders (designers or companies). The workshops are also a way for them to teach us folks from the urban centers, while we promote experimentation, risk-taking and innovative approaches using the materials they already work with. Many of them have told us that they never get to work this way.

The workshops are the true heart of the entire Typecraft process—going from a craft (such as embroidery) or a tribal art (like a tattoo) to letters and eventually the typeface. We work in a manner that is not top-down and patronizing, which is why each project requires some tweaking in terms of how to deal with disparate groups of people, in terms of their relationship with the opposite sex, how they work with materials and how much experimentation they might or might not have done before. We also learned that while most tattoo artist can draw very well, most craftspeople working with textiles (embroideries, weaves, appliqué, etc.) struggled to draw—as the designs are in their minds. This is an interesting challenge to overcome, so I bring this way of working back into the D schools I work with, where students so used to Google search and 100s of drawing tools and software have to first imagine the design or use other tools to come up with the solution.

In the craft workshop, we bring in paper-based tools to mimic the craft to make it easier to design quick and dirty—as the same thing done with embroidery could take up to two days just to get one letter! (And a letter that might not work!)

How did you find and recruit the craftspeople and tribal artists that you work with?

These people are not recruited but instead people we collaborate with. We sometimes meet the craftspeople or tribal artists at various craft melas or haats (bazaars/markets) that happen in big cities like Delhi, but also in smaller towns and villages. Or we get connected to these groups through an NGO working with them already.

W

You’ve said this is a way to bring money to the communities.

The Typecraft Initiative Trust is a not-for-profit foundation solely surviving on funding through grants and CSR funds. Money is brought into the communities initially through workshops that we conduct over a period of one to two weeks. Sometimes the workshops are repeated again if we need more results or if we work with the same group for different scripts or styles (such as a lowercase) of a typeface.

Many times, we go out of pocket to cover these workshops, in which we not only try to involve as many people from the community as possible to share the wealth but critically, we never bargain on their prices, and are usually paying rates that are higher than even local NGOs that have been working in the region for much longer than us. Once the font is ready and starts to make a sale, we need to first cover our costs that include our travel, stay, material costs, craftspersons costs (if not already covered by the grant), intern and employee fees, photographer fees and promotional fees. After this a royalty between 20–40% is given to the craftspeople.

We also make donations in the form of older computers, furniture, etc., to craftspeople that are in need of these things. During periods of high stress for craftspeople, such as during the COVID pandemic, we also give loans or royalties upfront with craftspeople we have already worked with. In one case, we started a project during COVID with a group of craftspeople, as they didn’t have any work for months.

What have you learned from this experience?

A lot! Humility and the value of indigenous design. The value of collaboration. And what does it mean to challenge the field of both graphic design and craft—for which this project is a true outlier. It is on the edge of functionality and legibility key to design, and it doesn’t possess the materiality that craft seeks even though each project starts by hand-making in the craft and material usually used by the community.

I learned that type design can be a way to bring people together, to do good for communities and the planet and also a way for graphic and type design to “redeem themselves” from their entrapment with corporate and industrialized mass production.

The key challenge remains how to make this an impactful project where the community themselves use the font—as part of their craft, but also in educating their children in an alphabet based on their own craft or tribal art.

Do you plan on expanding and otherwise transforming the workshops?

The workshops for the craftspeople form the core of the Typecraft process.

What is critical in these workshops is:

To ensure learning is not one way and not “top-down”—that we outsiders and transgressors can also learn from the community, their wisdom, their culture and craft.

Many of the people we work with don’t know how to draft—they know the designs in their minds and can directly embroidery, weave or tie-dye them onto cloth or the material they work with. While processes are valued by us, they are time-consuming to implement. As we know, the initial stages of design require experimentation and making lots of explorations that allow for failure and learning. This means that for each workshop we need to do our homework and prepare an easy to manipulate and cheap “design kit” that allows the craftspeople to manipulate these to mimic their crafts quickly and in facile manner.

An example is the kit we create for the Soof embroidery women, made of different sizes of right-angle triangles, diamonds, parallelograms, that mimic the designs in the craft itself. This allows the craftspeople to make fundamental forms like curves, straights and diagonals in a quick manner and translate those to letterforms.

Where we are expanding these workshops is to bring these into the design school classroom. Design students not only get to work in a tactile manner, in an “Eastern” way of designing where no drawings or sketches are allowed, but they have to find the best solution for a “design kit” for a given craft, and then themselves make letterforms.

Ideally, when possible, students are also included in Typecraft workshops with craftspeople in their village/town or city. Where not possible, like the recent workshops I conducted at the California College of Art and School of Visual Arts—they had to study these communities, their geographical, political and social conditions and what one can learn about their material culture, and the crafts they make. Additionally, if there are any connections to their religion, belief systems, their geography, etc., to the way the craft looks. This makes design education not only more empathetic but much more specific where the “client” is a real person with real needs and challenges, rather than an anonymous customer.

Like I did with students from Germany, where they spent three weeks in India visiting various maker communities across the country, I am hoping to do similar exchanges with students form the U.S. and other countries to not only build in cultural connections, but deeper understanding of how the majority of the world lives.

What have been your biggest surprise(s) going into and pursuing this project?

When I first started this project in 2011, and in fact even during my SVA days in 2004 and 2005 when I dabbled with lettering and Indian visual culture, I always saw this as a visual and aesthetic project. But what I realized over time is that this needed to be something far beyond mere craft and design coming together; it needed to address greater sociopolitical challenges such as patriarchy, discrimination of religious minorities, of people based on their caste or gender and also of tribal people who have been exploited by various corporations in collusion with various governments, both past and present.

While this is a tall ask for a small organization to try to solve, there are a few things we can do, such as using the power of choice to select the group we work with. To work with people not only who might need livelihood and exposure to new markets but also those who are facing discrimination of some kind. We also design posters and graphics using the typefaces to highlight some of these very issues.

I didn’t expect this project to be valued far more outside India than within the country. I expected more recognition from major design and craft awards in India and in the West, and also inclusion in design magazines—which to be honest has been a struggle! My guess is that since this project straddles craft, design and art—and hence is an outlier in all three of these areas of visual arts practice—that’s the reason it doesn’t easily find “takers.”

What can we gain by embracing craft?

The connection to tactility is key for human learning, experiencing, sharing and memory. Graphic design—now a mostly digital and non-tactile field—has lost its connection to hand-making (craft) and materiality, unlike other fields of design such as fashion, textiles, product and interiors. Those aspects were critical to graphic and type design as metal-smithing (for hot type); hand-carving of wood (for wood type); knowledge of paper and inks as well as cloth and thread (textiles) for book-binding. … These aspects as we are aware of them today have been severed from this field and belong to the domain of the book printer. In this sense the idea of the glyph relates to the word glyphein, or “to carve”—like one does with tattoos and other crafts as well.

Crafts have an important lesson for us especially in this age of “polycrisis,” where issues such as global climate change have been brought on by the onslaught of consumerism, with its systemic mass-production, mass-consumption and mass-waste cycles—something that graphic design, in collusion with industry, is guilty of propagating.

Craft in the “traditional sense” in places such as South Asia has been about working with natural materials, in a community (usually employing a system of barter, where resources are shared within the community), and work happens slowly—devoid of any trends—leading to less waste and excess. While all this might sound utopian, it’s not without social issues of caste discrimination that would have existed even in more idyllic village settings, nevertheless the detrimental impact on nature would have been far less than the current mess we have.

For Baiga tattoos, we are experimenting with the idea of typing the name of the tattoo to yield the actual icon; Bakkhar is … a tattoo motif signifying tiling the land (for agriculture).

The font itself is a tool that can be used to further explore and celebrate their designs. It can also teach people about the communal practices that have been banned by the British and still continue to not be allowed on Bewar or the practice of shifting agriculture that was key to this tribe, and even features in their songs and folklore.

And lastly, we want to move beyond the mere aesthetics of the artform—even though they are important signifiers, they don’t give us the complete picture of the colonization and continued oppression (what I call “internal colonization” by powerful corporations that work in collusion with corrupt governments) to control these resource-rich lands. For an artwork coming up in a show in Australia, I am experimenting with the idea that typing certain words in this font will change them to other words that are subversive and make you think about this community deeper than their aesthetics, which is key! So typing “tribal” could give you a word like “laborer,” or “land” gives “coal mine,” etc.

I feel this project is fairly misunderstood as it’s not mainstream design, not mainstream art nor is it mainstream craft!

AI and type design are inevitable, but how can you use AI in a way that enriches the medium rather than making it less materialistic and less tactile than it is? How can you bring in imperfection and mistakes in a world that seeks efficiency, accuracy and perfection? What does imperfection mean in such a world—and this imperfection is only possible with the hand, not the computer.