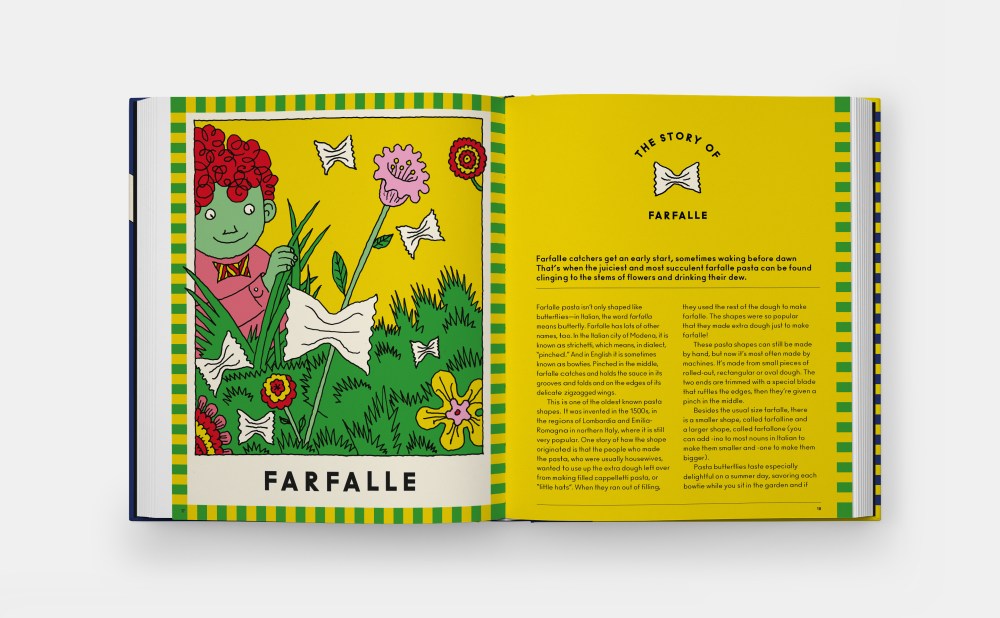

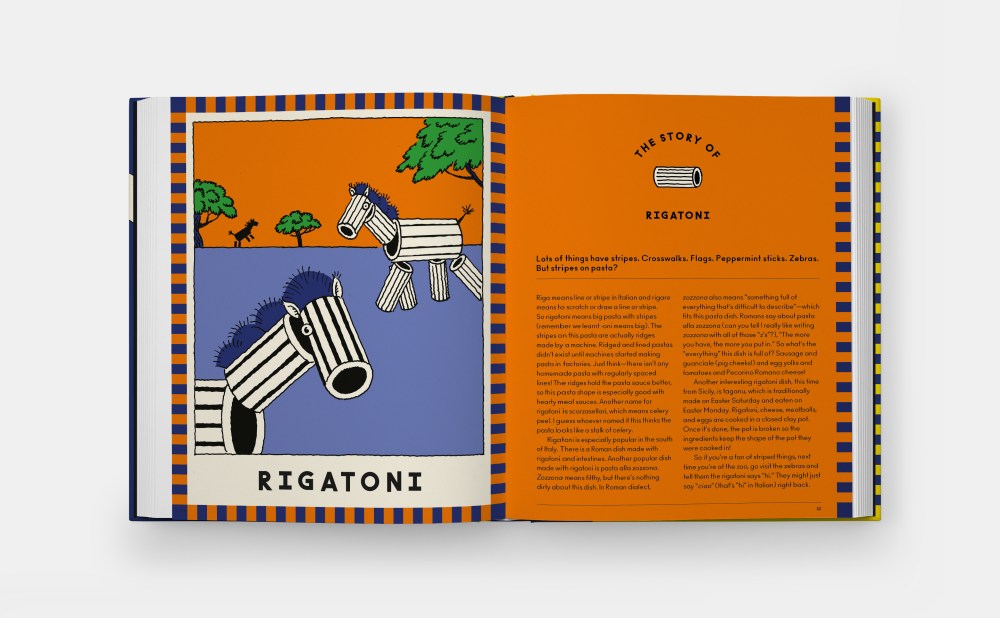

For many of us, spaghetti is the most comforting of all comfort foods. Carbs be damned, there is nothing better than twirling strands on fork and spoon. What many of us did not know when we were consuming gluttonous globs in cans of Chef Boyardee and Franco-American (??) was exactly how many different variations of fresh pasta existed in Italy, and that they come in shapes that look like screws, snails, butterflies and bowties, and called by such quirky names as “priest chokers” (strozzapreti) or “little ears” (orecchiette).

Steven Guarnaccia grew up in a home of pasta lovers. It is in his DNA (a strand of which would make a great pasta shape …). “I tend to be an improviser,” he told me about his passion for the gustatory delights. But more than cooking it, “I like arranging. There’s nothing I like more than a plate of pleasingly arranged, ready-to-eat ingredients from the fridge: salumi, cheese, leftovers and garnishes, with a couple of pieces of well-toasted bread on the side.”

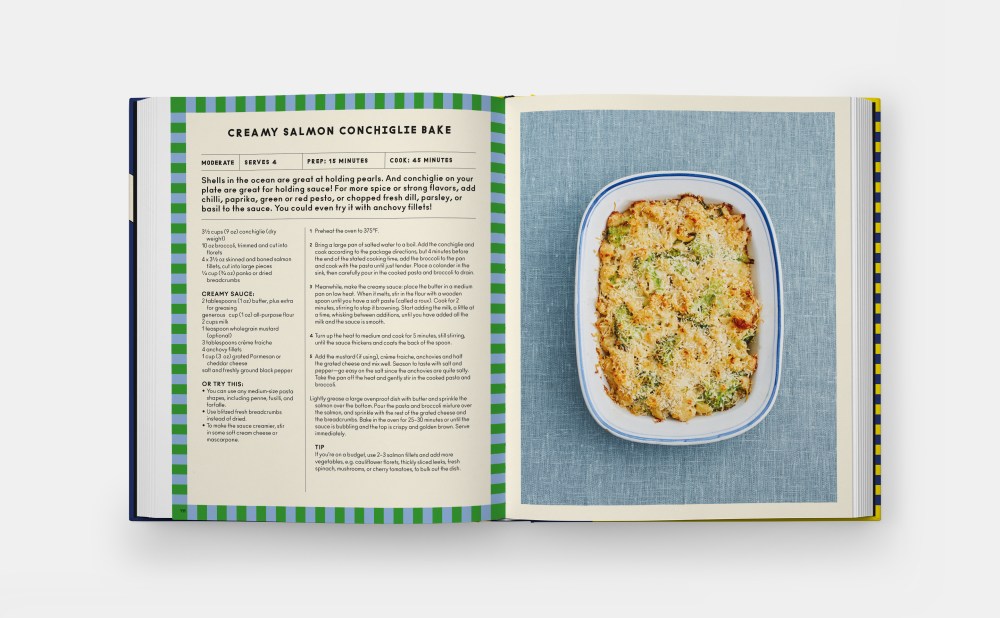

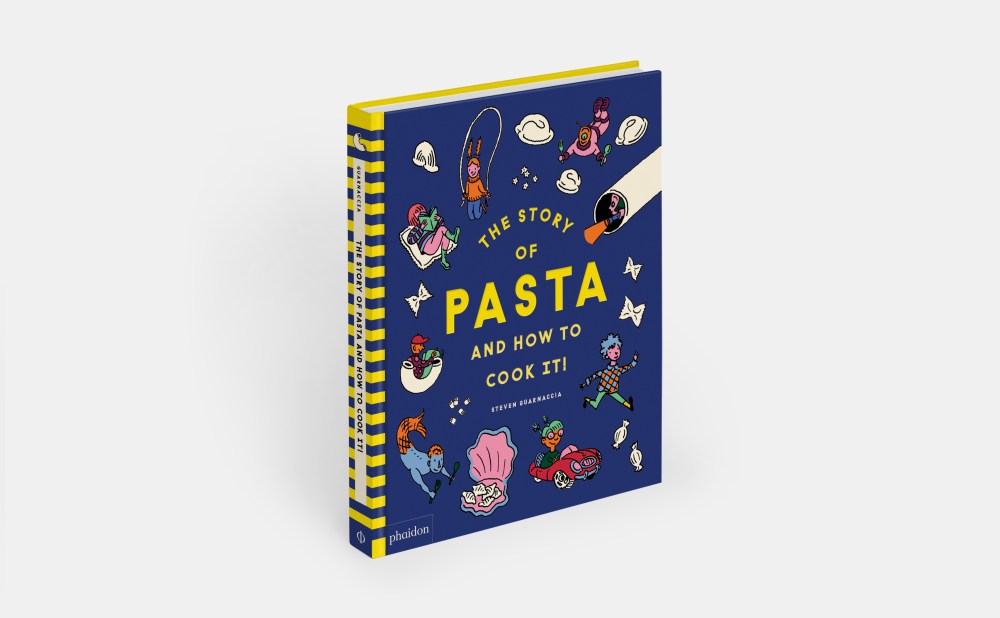

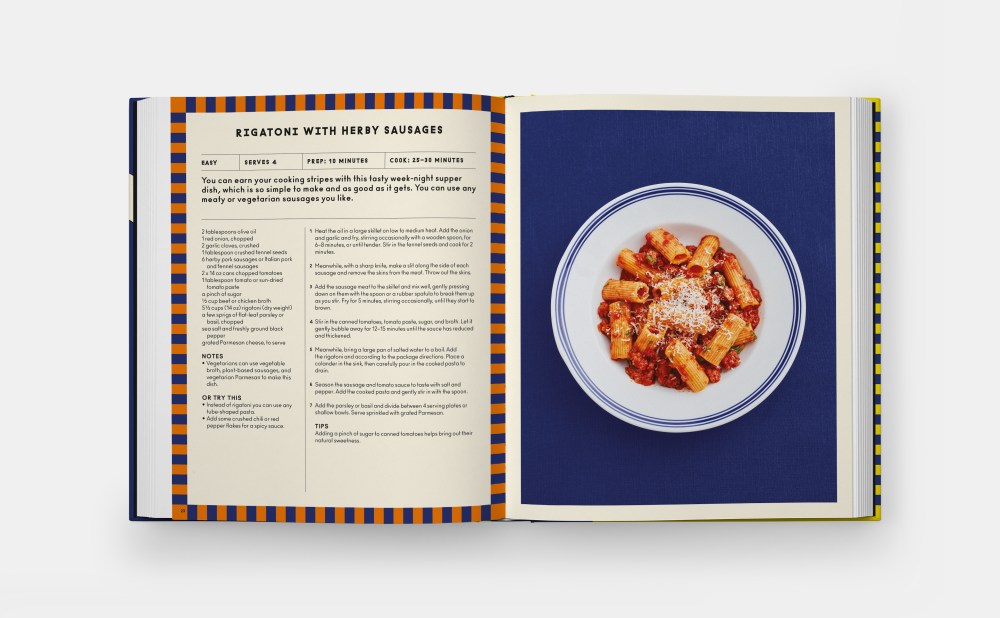

Known for his children’s books, Guarnaccia’s latest, The Story of Pasta and How to Cook It! (Phaidon), is a guide to pasta lore with recipes that children can make for their parents and friends. It is garnished with delightful drawings and delicious photographs. It is perfect for the the new wave of young chefs and their comfort-hungry parents. I asked Guarnaccia, long a friend and colleague, about the effects on his life and art of cooking and drawing pasta.

Do you like to cook pasta?

Pasta is really fun to cook. It takes a very short time, and it accepts almost any additions to the plate you can throw into it. In fact I like to cook the whole package even if I’m the only person eating (though my wife and 8-year-old daughter love to eat pasta as well), as it will make impromptu meals for days.

Did you cook all the recipes in your book?

The great kid-friendly recipes in the book are by Heather Thomas. I haven’t tried too many of them yet. I was too busy researching the really wonderful and at times wacky history of the various pasta names and shapes in the book, writing the text and coming up with unexpected images to illustrate the meaning of each shape.

Do you draw more than you cook?

I definitely draw more than I cook. But I draw more than I do almost anything. I’m almost always drawing, though not necessarily for any particular purpose. I’m what you might call an inveterate and constant drawer. Drawing is my default mode.

Do you cook drawings?

I don’t. But I have a friend and Corraini Edizioni colleague, Fausto Gilberti, who does. I was invited to give a children’s bookmaking workshop at Opla!, the archive of children’s books by artists in Merano, Italy. Fausto was in the next room teaching his group of young artists how to fry their drawings.

Do you cook up ideas?

I eat my way to ideas. I keep my sketchbook always at hand, and often get some of my favorite ideas sitting at the dining room table.

Are your ideas fully or half baked?

I’ll humor you here: I guess that the process of coming up with and drawing an idea can be likened to that of preparing a meal. You need to have all of your ingredients around you and measured, ready to be deployed—pencils and pens, sketchbook and paper, mental acuity and manual dexterity. Like I said earlier, I’m an improviser, so I don’t always know what I’m going to come up with when I sit down to cook my ideas. But I usually have a timeframe within which to work, and I have a rough idea of who and how many my final artwork is intended to serve. Now, that all said, there’s no guarantee that the dish will come out right every time. Some ideas need to be left in the oven a little longer, some should have come out way earlier. But fully- or half-baked, they all need to get to the table on time, or somebody is going to be hangry.

Have you vetted your cooking and drawing with testers?

My wife, Nora Krug, and my daughter Ava are my trusted tasters and testers.

Are you satiated by all this attention on your cooking, drawing, eating and conceptualizing?

I’m much more comfortable having my drawing and writing scrutinized than my cooking.

Are you really Italian?

My mom was third-generation German-Jewish, my dad was second-generation Sicilian, rather than Italian (Sicilians will know what I mean). I grew up between cultures. When I was in college, I realized: hey, I’m Italian (I hadn’t made the fine distinction between Sicily and mainland at that point)—I can go to Italy and be Italian (it didn’t turn out to be so easy; once there I felt more American than ever)! So I studied Italian at college (lackadaisically) and then took a year off (I’m still technically on a leave of absence from Brown) to go to Italy and learn the language in Perugia and study letterpress printing and typography in Urbino. My illustration career has been pretty much divided between work I do for clients in the U.S. and clients in Italy. I’ve taught illustration for a number of years in Urbino. Many of my children’s books were first published in Italian by the wonderful publisher (who we share) Corraini, based in Mantova. I go to Italy two or three times a year, partner with Bologna-based Hamelin on a visual book initiative in conjunction with the Bologna Children’s Book Fair called Talking Pictures, speak and email Italian friends and colleagues weekly in Italian. Sorry—what was the question again?

Is spaghetti really harvested from trees?

So, once upon a time, on April Fool’s Day in 1957, the BBC aired a short documentary about the spaghetti harvest in the Ticino region of Switzerland. England’s cuisine was not very Euro-aware, shall we say, at the time. There were scenes of spaghetti farmers with baskets, harvesting the strands of ripe spaghetti from spaghetti trees. There was even advice on how to breed trees that produced the correct length of spaghetti. Needless to say, there were requests to the BBC for advice on how to grow one’s own spaghetti trees. So in answer to your question, yes, spaghetti is really harvested from trees. And before you go, might I interest you in the purchase of the bridge that spans the East River from Manhattan to Brooklyn?