Animals are an increasingly vivid lens to see the world as remarkable and auspicious. Animals are also a fragile component of the Earth’s complex system, which humans have had a hand in preserving and destroying.

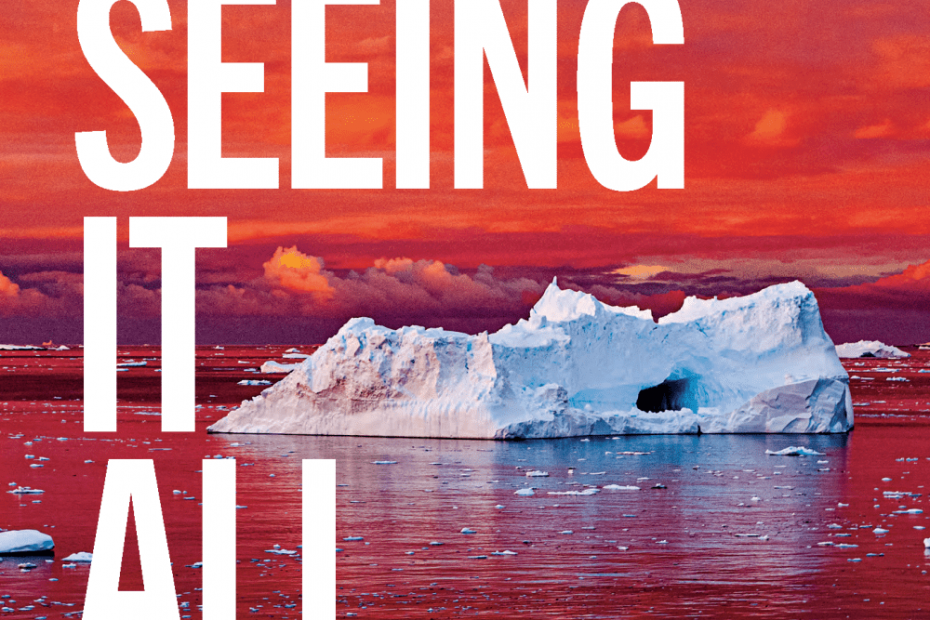

In her new book, Rhonda Rubinstein—creative director for The California Academy of Sciences and co-founder of its BigPicture Natural World Photography competition—turns the lens on the good, bad and tragic in the precious animal kingdom. A decade of searing images appear in Seeing It All: Women Photographers Expose Our Planet (Goff Books). Included are profoundly moving, decidedly awesome and breathtaking photographs of nature’s glory and fragility as captured by 11 visionary photographers who artfully document thriving and endangered environments from Africa to the Arctic.

The urgency of Seeing It All is expressed in the introduction by Rubinstein, plus a foreword by Sylvia Earle and essays by writer/historian/activist Rebecca Solnit, and neuroscientist/writer/stage director Indre Viskontas. I am anxious for you to read what Rubinstein has to say about the excerpted pages you are about to see.

This is a startling and at times heart-wrenching book. How did you get involved in this project?

Seeing It All evolved from a desire to create a book featuring influential female photographers and to share their powerful images about urgent environmental issues. It comes from a photography initiative that I co-founded at the California Academy of Sciences, where I have been working as creative director since 2008. Ten years ago, we launched the BigPicture Natural World Photography competition and exhibition to showcase wildlife and conservation stories in a thoroughly modern way. BigPicture has become one of the most prestigious global photography competitions in its field, revealing provocative stories from around the world and raising awareness about conservation issues.

Photographer: Ami Vitale

How did you find these amazing photographers?

All the photographers in the book have been either BigPicture winners, finalists or judges. This made it a little bit easier to select from the many women photographers doing great work in this field.

Photographer: Britta Jaschhinski

Why did you choose to focus on women photographers in the wild?

Why not? Most photography books are heavily weighted towards male photographers.

A few years ago as we were putting the finishing touches on the annual BigPicture exhibition at the museum, we noticed the relatively low number of women photographers’ work on display. That correlated with the lower proportion of women’s submissions in the competition. Not to mention photography in general. As you probably know, women photographers are underrepresented in most publications and media by an average of five to one. So producing a publication was a way to highlight the impressive work by female photographers. A book would allow us to delve deeper into the conservation issues that each photographer has focused on, as well as provide personal backstories as inspiration to young photographers and activists.

You write that the “beauty of these photographs enables us to look at what we’d rather not see.” Is this book a method of coming to grips with our failings, or a form of redemption?

The strength of Seeing It All is that the book uses beauty to entice and focus our attention on a subject, but there is not a uniform approach to depicting the state of the world. The photographs can be spectacular and beautiful but not necessarily pleasant or pretty. While Morgan Heim, who photographed roadkill surrounded by bouquets of lush flowers, calls this series of roadside memorials “Apologies,” the book is not about coming to grips with our failings nor a form of redemption. It is simply evidence of what is happening at this moment: We all recognize that we’re in this pivotal moment. Some people focus on the doom and despair of the biodiversity and climate crisis, while others see the opportunity of new solutions and actions towards a thriving future. In this case, it’s not either/or. Seeing It All shows us the better and the worse. The potential and the peril. Ultimately it is a book of hope. I believe that by exposing the issues—along with the magnificence and resilience—we will be moved towards the better. It’s a carefully crafted call to do more better and less worse.

Photographer: Britta Jaschinski

The images can be so magnificent on one spread and heart-tugging on the other. Was your intent to take the reader on a roller coaster under the sea and in the air?

The intent was not to bring your stomach to your throat, but it was certainly to elicit emotion! Many of the images are either heart-warming or heartbreaking, and I think it is critical to get that muscle working. It’s interesting to note that most books about the current state of the planet are either all about the beauty of the pristine “natural” world or the desecration that humans have wrought during the anthropocene. (Rebecca Solnit’s essay in the book brilliantly expands on the idea of the new ethos of nonseparation between humans and nature.) We deliberately combined the two in order to have the awe and inspiration of the former, and the anger and motivation to act, of the latter. It’s a way to reconcile the hope/despair dilemma—you can’t ignore what’s happening, but you can’t be overwhelmed in order to act.

Photographer: Cristina Mittermeier

All of your photographers take great leaps and risks to capture their shots. What, aside from the obvious feelings toward the health of the planet, do they share?

Yes, they are all committed to the health of the planet but take very different approaches in their work, which allows us to see the world through their eyes. I found three common threads that weave these unique perspectives together: compassion, connection and conscience.

The compassion is for other living beings beyond our immediate family of humans to our more distant relatives: other animals, plants and the planet itself. Jo-Anne McArthur’s work is particularly emblematic of that shift. She talks about the hierarchy of care, where we might feel empathy for the panda or the polar bear club and want to protect them. Meanwhile, there’s a huge category of animals that we raise in order to eat them. She photographs the torments that industrial agriculture has inflicted on individual chickens or pigs and insists we face them.

The connection is to and of everything. Intellectually we know that our lives depend on nature’s interconnected systems: the air we breathe, the water we drink, the food we eat. But Camille Seaman emotionally connects us to all of the world around us. Based on her Shinnecock ancestry, she sees plants, insects and all else as our literal relations, not resources. Even the magnificent Antarctic icebergs, through her lens, become portraits of ancient creatures.

The impact on our conscience is best articulated by Britta Jaschinski, who says, “Photography, filmmaking and journalism are among the most important professions on the planet. Without these, the world’s conscience would wither.” She photographed the National Wildlife Property Repository in Denver, which houses over 1.4 million wildlife products seized by federal authorities. Rhino horns, monkey skulls, stuffed tiger fetuses. It is not easy to gain access to these facilities, and areas that can be photographed are limited. So the impact of the illegal wildlife trade is not readily apparent. Thus the need for these photos as evidence.

Photographer: Daisy Gilardini

Some are interested in life and others are focused on death. What drives the passions of your photographers?

Each photographer has dedicated their work life to documenting a particular aspect of the natural world, whether it is portraying newborn animals and family life in the wild as a way to combat the crisis of kids’ disconnection to nature (Suzi Eszterhas) or revealing the ocean as one of the key solutions to climate change (Cristina Mittermeier). Each photographer has a unique approach to exposing the planet—which we distilled into the manifesto that begins each chapter. The 11 statements help the reader understand the philosophy and visual strategy that each of the 11 photographers employs in their image-making and storytelling.

What do you hope will be the outcome or consequence of this powerful document?

I stated it on the back cover: “These 11 photographers might change how you see the world,” particularly our relationship and connection to the natural world. After all, our wellbeing is only a few interconnected steps away from them. Another desired outcome is that by portraying these amazing, badass photographers who take on difficult and often dangerous shoots, we amplify their work and provide role models for young women.

Photographer: Suzi Eszterhas

Combined, perhaps this can help people navigate these extraordinary times. A lesson from these photographers is to focus on what you love and where you can make a difference. As Camille Seaman says, “Choose the one thing on this planet that you don’t want to disappear on your watch, whether it is a butterfly or a tree. Once you identify the thing you love most and cannot live without, you will find other people who are also passionate about it. And that’s where change begins.” We’ve used beauty and design to entice you to look at this book then consider, What is your one thing?

Photographer: Tui De Roy

Ed. note: Typefaces used in the book include Bezzia, which was designed by Lettermatic and inspired by the handwritten labels attached to specimens in the Entomology Collections at the California Academy of Sciences.