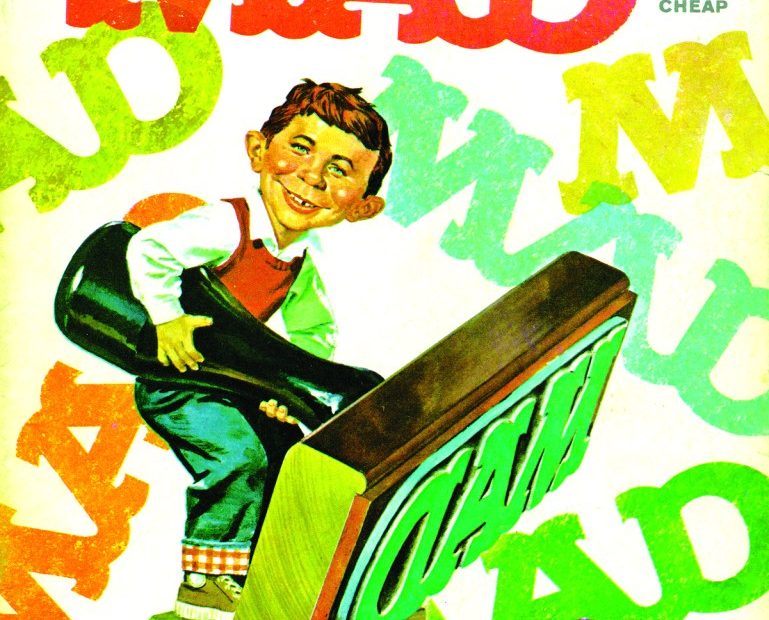

Most of my generation learned the meaning of humor and satire from MAD magazine. When I was 7 or 8 years old I frequently scrounged loose change from my father’s coat pockets to buy copies. One summer, I made enough money to buy all the MAD paperbacks that were for sale at the Cozy Nook luncheonette in Long Beach, Long Island, and spent a blissful two lazy months reading every strip, fake advert and feature. Whoever said the late ’50s were a drag never listened to Bob and Ray (who appeared regularly in MAD) or read MAD at all! So I am extremely pleased that The Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, MA, has replaced its Leo Lionni exhibition with What, Me Worry? The Art and Humor of MAD Magazine, which runs through Oct. 27.

The show covers the full legacy of MAD, from Harvey Kurtzman’s inspired comic book, to Bill Gaines’ outwitting the Comics Code Authority by transitioning from comic book to magazine format, up through the present. The NRM curatorial staff, headed by Stephanie Plunkett, together with guest curator Steve Brodner (assisted by an unusual gang of experts), has brought MAD—which ended newsstand distribution in 2018, continuing in comic book stores and via subscription—back to the fore with a richly filled treasury of printed and original material. I prevailed on Plunkett and Brodner before the opening on June 8 to discuss what and what not to worry about while visiting this MAD wellspring of humor in the jugular vein.

MAD was certainly inspiring to me as a kid. I caught the tail end of Kurtzman’s era. Why is this exhibition right for the NRM?

Stephanie Plunkett: The museum is one of the few institutions in the nation that is solely dedicated to the art of illustration, and to the creation of new scholarship relating to the field. Understanding the impact of published illustration within and beyond the context of its times has been central to our mission. MAD changed the way people viewed the world—we wanted to understand how and why that happened, and to share the work of artists, writers and staff who made it all possible.

Steve Brodner: The Rockwell Museum is not only a great venue for the Norman Rockwell collection, but also has become famous for showing work by a wide variety of artists and art movements. In 2008 I was fortunate enough to be the subject of one of those: a one-man show dedicated to work that was very much unlike the Rockwell genre. But it turned out to be a success in that it got people talking about political issues that were important at the time. This show gives us the opportunity to focus on several chapters in the life of satire, parody and humorous art in the United States. The museum commendably understands the importance of MAD to several generations of kids. The impact of that changed our culture in the immediate moment, and also in how many of those young readers would be inspired, like myself, to enter this fershlugginer profession.

What was the curatorial process of what was selected?

Plunkett: We began by working with award-winning satirical illustrator Steve Brodner and a group of 10 advisors, including MAD art directors, artists and writers, and an academic specialist in American Humor Studies, who gave us a more complete understanding of the topic and the important touchpoints to explore. They also helped to connect us to a wide range of artists from across MAD’s history, and we were grateful for their assistance. From there, we established both a MAD timeline through the publication’s editorial periods as well as some major themes that remained prominent through the years. We began reaching out to both MAD collectors and to individual artist to request loans of art and objects for display. Lenders have been extremely enthusiastic about the exhibition and they are passionate advocates for the publication and its contributors.

The group of advisors met several times via Zoom to discuss ideas.

Brodner: We began with [this] impressive panel of advisers from all walks of creative life. MAD magazine veterans, younger artists who have worked for MAD, and then branched out into their own careers. Writers and scholars. We had a number of meetings in which we discussed the format of the show and what work would best be chosen. It cannot be emphasized enough the contribution of Sam Viviano. He understood far better than I the workings and history of MAD. Having worked as an artist, and then designer, for many years, he is a kind of bridge between the original gang of idiots and successive generations. And then, to my surprise, Sam was able to help us find original art, a lot of which is on the walls of the show.

Is the story of the Comics Code Authority covered as the turning point in MAD‘s existence?

Plunkett: Yes, it most certainly is. By the end of 1954, with the creation of the Comics Code Authority, EC Comics crime and horror titles were retired but MAD remained, reinvented as a magazine on June 30, 1955 with issue No. 24. Though this helped MAD avoid content regulations imposed by the Comics Code Authority, Harvey Kurtzman was intent on recreating MAD as a magazine, a shift that Bill Gaines supported to keep his editor from defecting to Pageant, a monthly journal, for higher pay. After Kurtzman’s ultimate departure due to a disagreement of terms, Al Feldstein stepped in as editor with issue No. 29 in September 1956.

Is this exhibit instructive (or cautionary) in how censorship works, especially in relation to comics?

Plunkett: One of the key takeaways of the exhibition, I hope, will be MAD’s insistence on seeing through falsehoods and encouraging readers to question rather than accept. In the words of editor John Ficarra, “MAD’s editorial mission statement has always been the same. Everyone is lying to you. Think for yourself. Question authority.”

B

What is the organization of the exhibit?

Plunkett: The exhibition will be organized chronologically by editorial periods, with insets focused on specific themes. Here is an abbreviated description of the editorial periods:

1. 1952–1956: THE KURTZMAN YEARS: Harvey Kurtzman began working for William M. Gaines’ EC Comics in 1950, editing anti-war cautionary tales disguised as adventure comics. Debuting in late summer 1952, his Tales Calculated to Drive You MAD—or, more simply, MAD—was unlike any comic book then on the stands. In fact, its entire purpose was to make fun of other comics.

After a slow start, MAD hit paydirt with issue No. 4, which featured “Superduperman,” illustrated by Wally Wood. Sales soared and Kurtzman followed with parodies of other superheroes and takedowns of comic strips, TV shows, movies and politics. Two years into its run, Kurtzman tried to convince Gaines to retool MAD as a magazine. With the comic book industry under pressure from Congress, Gaines granted Kurtzman’s request. Issue No. 24, dubbed “the New MAD,” appeared in spring of 1955.

2. 1956–1964: THE FELDSTEIN REBUILD: On the heels of MAD’s success, Kurtzman approached Gaines, demanding majority ownership of the magazine. When Gaines refused, Kurtzman left EC and took his talents—along with Will Elder, Jack Davis and Al Jaffee—to Playboy’s Hugh Hefner, who bankrolled a slick color humor magazine titled Trump. It lasted two issues.

With no editor, Gaines reached out to Al Feldstein, who had helmed most of the EC Comics line, and put him in the editor’s chair. With the help of associate editors Jerry DeFuccio and Nick Meglin and art director John Putnam, Feldstein recruited freelancers whose names would become synonymous with MAD—writers Frank Jacobs and Tom Koch; artists Bob Clarke, Kelly Freas, Mort Drucker and George Woodbridge; and cartoonists Don Martin and Dave Berg. He also commissioned Norman Mingo to paint the official portrait of Alfred E. Neuman for the cover of issue No. 30. Feldstein added more MAD legends, including writers Larry Siegel, Arnie Kogen, Dick DeBartolo, Lou Silverstone and Stan Hart; artists Paul Coker and Jack Rickard; cartoonists Antonio Prohias, Duck Edwing and Sergio Aragonés; and photographer Lester Krauss, as well as “The Lighter Side of…,” “Spy vs. Spy,” and Al Jaffee’s Fold-ins, which debuted in 1964 in issue No. 86.

3. 1965–1980: THE CLASSIC ERA: Once the basic formula was set, Feldstein allowed his writers and artists to do what they did best: create sophisticated satire and sophomoric humor. MAD’s anti-smoking campaign and anti–Vietnam War articles gave added weight to its commentary. Irving Schild became MAD’s photographer, while artists Angelo Torres, Bob Jones and Harry North joined “The Usual Gang of Idiots,” along with cartoonists Paul Peter Porges and John Caldwell. In the late ’70s, writers Dennis Snee, Barry Liebmann, Mike Snider and John Ficarra became contributors. MAD’s popularity was at a high, with its circulation reaching over 2.5 million by 1973.

The era ended with two significant losses: Norman Mingo died in May 1980, and art director John Putnam passed away six months later. Production manager Leonard Brenner moved into the art director’s chair, and Jack Rickard assumed the role of MAD’s primary cover artist.

4. 1981–1992: THE TORCH IS PASSED: After 29 years as editor, Al Feldstein retired from MAD in 1984. Nick Meglin and John Ficarra became co-editors, and would run the magazine together for the next two decades, supported by associate editors Charlie Kadau and Joe Raiola, and office manager Annie Griffiths Gaines. Richard Williams became the main cover artist in 1983, and others, including artists Sam Viviano, James Warhola, Gerry Gersten, Rick Tulka and Tom Bunk; writers Desmond Devlin, Russ Cooper and Darren Johnson; and cartoonists Tom Hachtman and Tom Cheney came on board.

Bill Gaines, publisher and guiding spirit of MAD, died on June 3, 1992, at the age of 70. A full-page ad in The New York Times featured Alfred with a tear in his eye and the staff’s promise to continue “the laughter, the irreverence and the mischief.”

5. 1993–2009: THE DC YEARS: Gaines had sold MAD in the early ’60s, and when he died it soon came under the aegis of DC Comics, a Time Warner company. Meglin and Ficarra were charged with rebooting the magazine to make it edgier, adding new features like “The MAD 20 Dumbest People, Events and Things,” the bestselling end-of-year roundup. Writers Frank Santopadre, Michael Gallagher, Anthony Barbieri, Scott Maiko and Jeff Kruse; artists C.F. Payne, Drew Friedman, Rick Geary, Bob Staake, Hermann Mejia, Roberto Parada and Mark Stutzman; and cartoonists P.C. Vey and Peter Kuper published their first work in MAD in the 1990s. In 2003, Mark Fredrickson became MAD’s primary cover artist and is now the most published as well.

Sam Viviano became art director in 1999, ushering MAD into the digital era and overseeing its conversion to a full-color magazine. “Fundalini Pages” and “The Strip Club” introduced next generation cartoonists Teresa Burns Parkhurst, Keith Knight and Emily Flake; writers Stan Sinberg and Tim Carvell; and artists Tom Richmond, Liz Lomax and Ward Sutton. In 2004, Meglin retired after five decades, and Ficarra remained at the helm until 2017.

6. 2009–2017: THE WARNER BROS. YEARS: The Great Recession of 2008 had an effect on MAD, including staff reductions, freelance rate decreases, and the cancellation of MAD Specials and the newly launched MADKids. Diane Nelson moved over from the movie division at Warner Bros. to head DC and established a plan to move the entire company to Burbank, CA. The New York office was closed at the end of 2017, and a new staff was hired to relaunch the magazine from Burbank the following year. By 2020, only art director Suzy Hutchinson and associate art director Bern Mendoza remained, overseeing an active reprint version of MAD featuring some new covers, fold-ins, features, and specials that continue its legacy today.

Who are the most prominent artists in the exhibit?

Plunkett: The Usual Gang of Idiots, as they termed themselves, including Wally Wood, Jack Davis, Norman Mingo, Dave Berg, Will Elder, Harvey Kurtzman, Kelly Freas, Mort Drucker, Antonio Prohias, Angelo Torres, Don Martin, Sergio Aragonés, Al Jaffee, Ray Alma, George Woodbridge, Tom Bunk, Robeto Parada, Sam Vivviano and others, as well as next-generation artists Peter Kuper, Herman Mejias, Mark Fredrickson, Mark Stutzman, James Warhola, Liz Lomax, Scott Bricher, Dale Stephanos, Drew Friedman, C.F. Payne and cartoonists Don Edwing, Keith Knight, Emily Flake, John Caldwell and Teresa Burns Parkhurst.

How is MAD positioned in relation to visual humor and satiric art today?

Plunkett: We’ll be hosting a symposium on Oct. 18 and 19 called The Usual Gang of Idiots and Other Suspects: MAD Magazine and American Humor Since 1952, featuring a wide range of commentators, in addition to other programming. A compendium exhibition, Rockwell and Humor, will explore Rockwell’s approach to humor for Midcentury magazines.

Brodner: MAD’s position, historically, to me, was as a key platform for talent that defined humor in American culture. And as the wellspring for work done by those artists and writers going forward. This expanded out to television, radio, films, novels and comics.

What, if anything, continues to have sociopolitical relevance looking at MAD today?

Plunkett: MAD questioned everything, and nothing escaped their scrutiny. We live in a world where it is increasingly difficult to distinguish between what is real and what is imagined, culturally and technologically. It is more important than ever to cast a discerning eye on the world around to understand more clearly what is really going on, a message that MAD has emphasized through the years.

Brodner: All those writers and artists were tackling exactly the same things we are confronting today. Significant sections of the United States at that time were tragically unhip. They were so locked into their monoculture and terror of change that they couldn’t see the changes that were taking place all around them. We, as kids and MAD readers, could see through all of that: in advertising, news coverage, crap culture, etc. Those of us working in media today in a commentary capacity are facing the same demons, the same issues, the same immensity of bullshit. So MAD gives us the template and the courage for fighting back … and the sneaking suspicion that we can succeed again.