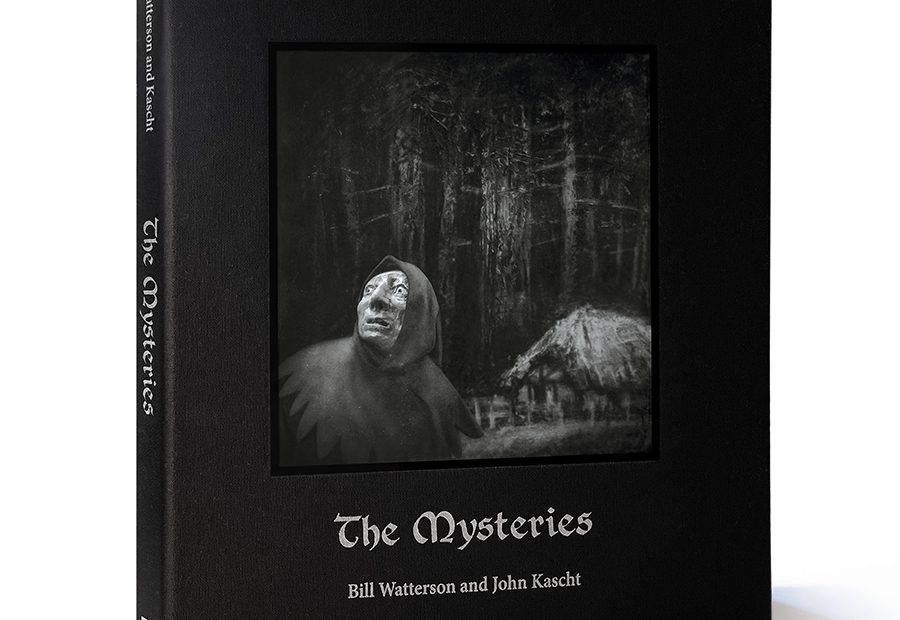

Combine the imaginations of Calvin & Hobbes creator Bill Watterson and premier caricaturist John Kascht, throw in an enigmatic story without a plot or trigger for illustration … and the results will surprise everyone, including the collaborators. This video is as good an explanation as possible (watch it!).

During his bout with long COVID this winter, I asked Kascht to tell me his side of this unique meeting of the arts and artists that resulted in The Mysteries.

The book is splendidly eerie, and the illustrations carry the load. How did you and Bill Watterson come to collaborate on this project?

Bill and I had been talking about wanting new directions in our work, and the idea of collaborating came up. We brainstormed about what and how. Bill mentioned a story he wrote that was languishing in a desk drawer, and he said it was unillustratable. That sounded pretty interesting.

I read it, then read it again. Then a third time.

The Mysteries has a weird not-thereness that appealed to me right off. The words are straightforward but the story itself is elusive. It sinks in differently with each reading. There is no character development, and no narrative progression in the usual sense. Most of the action takes place between the lines and out of the picture frame. There is almost no visual description. I wasn’t sure it was unillustratable but certainly not illustratable by conventional methods.

Bill and I decided to try, as an experiment. Initially there was no plan to publish the results. We agreed to consider publishing only after we had finished, only if we had something worth sharing. We wanted the art to evolve on its own terms with no external pressures and no thoughts of an audience.

The ground rules were simple; either of us could veto any part of the work, even bail out of the project at any time.

Having equal say sounds ideal but it’s actually a tough way to work. Bill likened it to driving a car with two steering wheels. We made a short video about the experience.

How did you decide on a style?

Decide? Wow, no. The style found us. Starting out we assumed we’d discover a Goldilocks zone where our skills overlapped and we’d work from there. Instead we discovered that we overlapped about as much as two islands.

The breakthrough came when we surrendered and accepted that we were never going to find some magic style that split the difference between us. We decided to come at the pictures as ourselves and put our marks on every inch of the pictures however we wanted. That kind of improvisation is more familiar to musicians than visual artists.

Since neither of you are known for this kind of noir mood, who decided to do what?

By design, a lot of things in Bill’s story aren’t described (mysteries, after all), so the pictures had to leave a lot unseen. Depicting specific visual content was less important than conjuring a mood, a feeling. “Feeling” is hard to storyboard, so we didn’t. We just started working on what might become a finished picture, and if it started to feel wrong, we tried something else. We couldn’t envision the pictures upfront; we had to find them by groping around in the dark. Which befits a story about unknowable things, I guess, but what a crazy way to work.

In retrospect, I see how the intensity of the collaboration seeped into the pictures and gave them a weird energy that couldn’t have come from a conventional process. The countless hours of work, the constant changes in direction, the mountain of objects made and rejected, the struggle … somehow it’s all there in the off-kilter world of the pictures. You sense conditions fomenting beneath the surface. Our challenging process itself created the mood, the feeling we were after all along.

I’m assuming that most of the character design was your hand?

Yes, but the figures look the way they do because of Bill’s involvement. We discussed every aspect of every picture. No matter who did the physical construction of this or that piece, we both have DNA in every bit of it. The results don’t look like either one of us, but apparently this is how we look together. Our mutual friend Peter DeSeve said it was like a third artist showed up and took over.

The Mysteries is apocalyptic. You’re mixing together vintage fairy tale with contemporary technology—is this a prophesy of what will come, or what could come?

That’s above my pay grade. I’m a simple maker of pictures.

I love the spread “Gradually the people stopped fearing the Mysteries. They laughed at the old paintings.” There is a museum guard sitting next to a painting of a rider of the apocalypse flying over a burning city.

I love that one too. So does Watterson. His Death on a Pale Horse painting is truly sublime. And funny.

Screenshot

This is certainly a prophetic image that has already come true—a jet flying over a modern city, which is notable in light of the Alaska Airlines plane that lost its door midair. How do you think your other predictions will fare in the time to come?

No clue, but I agree it’s impossible to ignore the ripped-from-the-headlines parallels.

We worked on these pictures for years against a backdrop of metastatic social and political pain, a pandemic, floods, fires, invasions, record heat and wind and smoky air. The story became less and less archetypal and more and more immediate. When we started The Mysteries, it was an impressionistic fable. By the time we finished it was … the zeitgeist. Nonfiction. The spooky part? Bill wrote it over a decade ago.

Screenshot

Who do you hope your audience will be?

I have faith it is finding its audience. I’ve heard stories about people receiving a copy of The Mysteries from an anonymous sender and then passing it along to someone else anonymously. Right now it’s being translated into five languages. It has a life.

Is there a plan to make this into a film?

There is a plan not to make it into a film. Maybe Mysteries action figures, though. Watterson will sign off on that, right?