The most damaging phrase in the language is: ‘We’ve always done it this way!’ A system cannot evolve if it cannot question its parts and their relationships.”

Donella H. Meadows, Author, Thinking in Systems: A Primer

I recently came across closed-bottle terrariums, and I’m fascinated by how they work. If you’re unfamiliar, picture a ship in a bottle, except it’s not a ship; it’s a small garden, and the bottle is closed up tight — nothing gets in or out (except light). When you look at them, they look more like miniature worlds, thriving in isolation, as self-sustaining ecosystems encased in glass. Somehow, the complex systems and interdependencies between the living and inert elements within maintain a delicate balance to support life without external intervention.

The oldest known closed-bottle terrarium is a marvel created by a British electrical engineer named David Latimer. On Easter Sunday 1960, Latimer added some compost and carefully planted a seedling in a large glass bottle; he poured in about a quarter pint of water and sealed it shut. He has only opened the bottle once, in 1972, to give his terrarium another small drink of water. Over the decades, his enclosed garden has continued flourishing, with the plant growing, photosynthesizing, and recycling nutrients within its glass confines. It’s a testament to the resilience and power of closed-loop systems.

How do these closed terrariums work? At its core, a closed-bottle terrarium is a microcosm of our larger ecosystem. It relies on balanced flows of light, water, and air — all sealed within its glass walls. Light is the energy that enables the plant to photosynthesize, producing oxygen and glucose from carbon dioxide and water. The plant, in turn, releases water vapor, which condenses on the walls of the container and trickles back into the soil, like a miniature water cycle. Microorganisms in the soil decompose dead organic material, releasing nutrients back into the soil and generating carbon dioxide, which the plant can reuse. This continuous cycle and interplay of elements and systems is what keeps the terrarium alive.

Systems

The brilliance of Latimer’s 64-year-old closed-bottle terrarium lies not just in its longevity but in its interrelated systems. It illustrates how components within a system interact in complex, interdependent ways to maintain balance and sustainability. Each element of the terrarium plays a critical role, and their interactions ensure the system’s health and longevity.

Donella Meadows, the environmental scientist and expert on systems thinking, defined a system as “a set of related components that work together in a particular environment to perform whatever functions are required to achieve the system’s objective.” A system is a set of parts that interact with each other to function as a whole and interact with the environment.

Our lives consist of countless systems. For how small it is, a closed-bottle terrarium is a very complex system. Let’s look at a simpler one to better understand how systems work: Meadow’s classic example of your home heating system. In her book Thinking in Systems, A Primer, Meadows explains systems as relationships between stocks and flows.

Stocks represent the elements within a system that you can measure at any given time. They are the accumulations of resources or capabilities within the system. Examples of stocks can include the amount of water in a reservoir, the number of people in a company, the money in a bank account, or even the amount of trust within a community. Stocks change over time through the flows that feed into or drain out of them.

Flows, therefore, are the rates at which stocks change. These can be inputs into the stock (inflows) or outputs from the stock (outflows). Flows are the activities or processes that increase or decrease the stock. For instance, in the case of a water reservoir, inflows might include rainwater or rivers flowing into the reservoir, while outflows might consist of water being drawn for agricultural use or evaporating into the air.

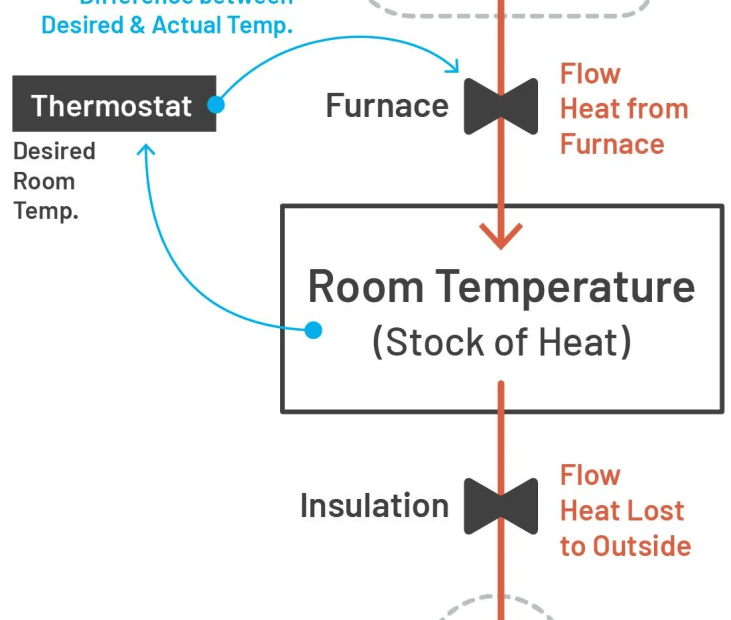

Adapted System Diagram from Thinking in Systems: A Primer, by Donella Meadows

In a home heating system, the stock is the room temperature or the amount of heat in the room measured by degrees Fahrenheit. There are two flows: an inflow of heat from the furnace and an outflow of heat leaving the room. What regulates those flows and our stock of heat is a feedback loop.

The interplay between stocks and flows can create feedback loops where the state of the stock affects the flow rates, which in turn affects the stock. Here, the feedback loop characterizes the discrepancy between the desired and actual temperature. As heat flows out of the room, the temperature falls; the thermostat measures that discrepancy and turns on the furnace to inflow more heat. The system continues to keep the room temperature balanced at your desired state. Note that changes in flows may not instantly affect the stocks due to delays in the system, which can lead to oscillations or delays in responses that require making effective management decisions. For this example, imagine if the thermostat could only accurately sample the room temperature every 6 hours. To keep the stock of heat stable, additional management would be required to predict and administer the flow of heat from the furnace.

Systems can be as simple as a room, a furnace, and a thermostat; or as complex as a business, with all its components, interconnections, functions, and purposes. Understanding how systems work can unlock opportunities and a ton of value for companies and customers.

Thinking in Systems

Systems thinking is an approach to creative problem-solving that focuses on how a system’s constituent parts connect, relate, and nest within the context of larger systems. Modern businesses operate in environments that are increasingly complex and interconnected. Systems thinking helps business designers understand and navigate this complexity by seeing the whole picture, including the various interdependencies and the potential for emergent behavior that isn’t predictable from looking at the parts alone. Leaders can make more informed decisions by understanding the relationships and feedback loops within and outside the organization.

Systems thinking enables the identification of leverage points where strategic interventions can lead to significant positive changes or avoid unintended consequences. Seeing the business as a system can foster innovation by revealing opportunities for synergy between different parts of the organization or with external partners. It encourages looking beyond traditional boundaries to find new ways to create value.

Let’s use a simple business example before widening our aperture: a lemonade stand. A lemonade stand is a system — its stocks include supplies (measured in number of lemons and pound of sugar), lemonade inventory (measured in fluid ounces of lemonade ready to sell), and cash (measured in dollars). There are also flows: purchasing uses cash to increase the stock of supplies; production, when we make lemonade, we decrease the amount of supplies and increase the amount of inventory; and sales reduce the amount of inventory and increase the amount of cash.

Our customers are also systems — living, breathing, moving systems. People have so many stocks and flows that there isn’t enough space in this newsletter to list them, so for the purposes of our example, let’s skip the details and just say humans have a stock of thirst, a stock of cash, and a stock of lemonade. Their purchase flow decreases their cash but increases their own stock of lemonade (usually one glass) and decreases their stock of thirst (which is a good thing).

Even this seemingly straightforward business has feedback loops and external factors that influence the system. There’s a quality feedback loop: the quality of lemonade could affect demand and sales. There’s also a customer demand feedback loop that influences future spending on supplies and how much lemonade the stand should produce. Externally, weather plays a part; a hot, sunny day could dramatically increase sales, while a cold, rainy day could push them to zero.

All these system elements interact to achieve various purposes—for the lemonade stand owner, they generate profit, and for the customer, they quench their thirst. For the business designer, seeing the system in its totality, including the relationship between elements, allows us to design these interconnections, optimizing them for our goals and purposes.

Yes, as designers, we must design individual touchpoints; for example, we could hone our product design by getting our lemonade recipe just right. We can also design how things connect, like a flow — our production system — to ensure we’re efficiently using our supplies to make that product. We can design how we track and respond to demand — if sales are way up on hot days, we could design a pricing strategy and test it; perhaps we could raise the price per cup dynamically based on the weather. Designing the business means designing the systems that create, distribute, and capture value.

Business Systems

As the lemonade stand example shows, we can conceptualize a business as a complex system comprised of multiple interconnected components like people, resources, cash, and culture. Flows, like our lemonade stand, include the flow of money through purchasing, sales, profits, costs, and re-investment; the flow of information through communication; and the flows of materials and activities defined by key production and distribution processes the company defines to create and deliver value.

These elements interact dynamically with one another and with external environmental factors such as market conditions, economic cycles, technological advances, and social and political forces, influencing the business’s ability to adapt, learn, and ultimately thrive. Feedback loops play an important role in bridging the business and the environment—continuous feedback from the market, customers, and internal processes informs decision-making and helps refine strategies and operations.

While the primary goal of most businesses is to generate profit and create value for stakeholders, businesses often pursue broader objectives that may include sustainability, social responsibility, and innovation. The effectiveness with which a company achieves these objectives largely depends on how well its internal components work in concert and respond to external pressures. Systems thinking enables business leaders to see beyond isolated parts of their organization, understanding how these parts connect and influence one another and the environment. This holistic view is crucial for strategic decision-making, allowing businesses to navigate complexities and devise solutions that are effective in the short term and sustainable in the long run. Let’s look at some examples.

Toyota Production System

The Toyota Production System (TPS) is a classic example of systems thinking applied successfully in business. Developed by Toyota Motor Corporation in Japan, TPS revolutionized automotive manufacturing, introducing principles and practices that enhanced efficiency, quality, and responsiveness.

During the post-World War II era, Toyota faced significant challenges, including limited resources, high production costs, and a small domestic car market. In the 1950s, a delegation of Toyota executives and engineers visited the United States to tour U.S. automakers’ factories to learn from the competition. What they saw did not impress them. Traditional mass production techniques were inefficient and wasteful, often yielding defects and low-quality goods. Moreover, the way American carmakers addressed their market — focused on high volume and low variety — was not viable for the challenges Toyota faced.

The group of Toyota leaders, including engineer Taiichi Ohno, also visited an American supermarket — a Piggly Wiggly, to be exact. During this time, supermarkets didn’t exist in Japan, and the team was curious — they didn’t expect to be inspired. They saw how the supermarket handled their inventory — Piggly Wiggly only reordered and restocked items once customers had made purchases (it sounds simple and obvious now, doesn’t it?). Back in Japan, Ohno, with the support of Eiji Toyoda, a member of Toyota’s founding family, applied the lessons of supermarket inventory management to how materials and parts flow into the manufacturing process only when and where they’re needed.

Key to the success of TPS was its holistic integration of these principles into a cohesive system. They could have analyzed each part of the manufacturing process and tried to optimize it in isolation, disconnected from the rest, but systems thinking enabled Toyota to see the production process as an interconnected whole rather than a series of separate segments — everything is connected — allowing them to identify and eliminate inefficiencies throughout the system.

Taiichi Ohno — Source: Toyota

Ohno and his team developed the critical component of the Toyota Production System: Just-In-Time (JIT), a methodology aimed at reducing the flow times within production as well as response times from suppliers and to customers. JIT helps in managing inventory levels effectively, ensuring that parts get ordered and received as needed in the production process. Feedback loops were also critical in TPS — workers on the production floor continuously fed information back into the system to help identify bottlenecks and areas for improvement. Toyota could adapt its processes dynamically, enhancing flexibility and responsiveness to changes in demand or production conditions.

Implementing TPS led to dramatic improvements in efficiency and product quality at Toyota. The system reduced costs by eliminating waste, improved flexibility in managing production variability, and enhanced customer satisfaction with higher-quality vehicles. Toyota is now the world’s largest automobile manufacturer, producing around 11 million vehicles annually with a 10.7% global market share. The success of TPS also influenced manufacturing processes worldwide, leading to its adaptation across diverse industries.

Southwest Airlines

Southwest Airlines, the U.S. airline known for its low-cost, high-efficiency model, has successfully utilized systems thinking to create a robust business model that sets it apart from competitors — even within the volatile airline industry, often plagued by economic downturns, fluctuating fuel prices, and intense competition.

Southwest Airlines started by offering low-cost, convenient air travel within Texas, directly challenging the conventional business models of existing carriers. Herb Kelleher, leveraging his legal background and entrepreneurial spirit, along with his co-founder Rollin King’s aviation experience, designed an airline model that differed fundamentally from the traditional hub-and-spoke systems used by other airlines.

Southwest employees accepting delivery of their first three Boeing 737s, 1980 — Source: Southwest Airlines

Kelleher and King applied systems thinking by viewing the airline as an interconnected system where each component affects and is affected by others. One of Southwest’s earliest and most significant decisions was to operate a single aircraft model, the Boeing 737 — this choice streamlined maintenance, training, and scheduling. By reducing the complexity associated with handling multiple types of aircraft, Southwest could focus on quick turnarounds and maintain high aircraft utilization rates.

Contrary to the popular hub-and-spoke model, Southwest adopted a point-to-point routing system — literally designing how its planes flow across the country. This strategic decision minimized the chances of flight delays and lowered transit times, greatly enhancing customer satisfaction and operational reliability. It also allowed Southwest to maximize the productivity of its fleet, as planes spent more time flying routes and less time waiting on the ground.

Feedback is also highly utilized by the airline. For instance, pilot and crew feedback enhances flight operations and scheduling. Customer feedback directly influences service offerings and marketing strategies, ensuring that the airline remains responsive to passenger needs. By understanding and managing the airline as a cohesive system, Southwest has been able to innovate its business model, streamline operations, and maintain a strong corporate culture.

U.K. Agricultural Policy

The U.K.’s agricultural policy has undergone significant changes, particularly following its exit from the European Union. These changes necessitated reevaluating policies governing agriculture, focusing on sustainability, efficiency, and competitiveness in the global market. The complexity of agricultural systems, influenced by environmental factors, economic pressures, and social expectations, required a comprehensive approach.

The primary challenge was to design a policy framework that could address multiple, often conflicting, objectives such as enhancing food security, reducing environmental impacts, supporting rural economies, and complying with new trade regulations post-Brexit.

The U.K. government adopted systems thinking to holistically address the intricate dynamics of agricultural policy — starting with understanding different perspectives and the relationships between various system components. The government initiated broad consultations with farmers, environmental groups, industry representatives, and scientists to gather diverse insights into the agricultural system. Recognizing that changes in one part of the agricultural system could have wide-ranging effects on others, the policy aimed to integrate goals related to productivity, environmental sustainability, and economic viability — to best balance trade-offs and synergize efforts across different sectors.

The cornerstone of the new policy, outlined in the Agriculture Act of 2020, was an approach called Environmental Land Management Schemes (ELMS), which focuses on paying farmers for “public goods” such as environmental improvements and conversation efforts, including actions to improve soil health, water quality, and biodiversity. To comply with the policy and receive incentive-based payments, farmers have begun implementing more environmentally friendly practices, such as reduced pesticide use, cover cropping, improved water management, and better living conditions for farm animals.

The new policy framework also incorporated ongoing monitoring and feedback mechanisms, allowing adjustments based on outcomes and the latest information. This adaptive management approach was crucial in a sector heavily impacted by external factors like weather conditions and global market prices.

Business Benefits of Systems Thinking

Systems thinking offers profound benefits to businesses — organizations who embrace this holistic approach can realize several key advantages:

Enhanced Problem Solving: Systems thinking enables businesses to see beyond surface-level issues and understand the underlying complexities of challenges. This deeper insight leads to more innovative, effective, and sustainable solutions that drive competitive advantage rather than temporary fixes that fail to address the root causes of problems.

Increased Efficiency: Companies can identify inefficiencies and eliminate waste across processes by analyzing how different parts of a system interact — leading to smoother operations, reduced costs, and better resource management, ultimately enhancing overall productivity.

Improved Adaptability: Adaptability is crucial in today’s rapidly changing business environment. Systems thinking fosters an environment of continuous learning and feedback, which equips businesses to respond dynamically to market shifts, technological innovations, and evolving consumer preferences.

Stronger Strategic Planning: Systems thinking provides a framework for understanding the immediate effects of decisions and their longer-term impacts on all parts of the organization and its external environment — supporting more robust strategic planning and risk management.

Enhanced Stakeholder Relationships: Systems thinking also helps businesses understand and prioritize the needs and expectations of various stakeholders, including customers, employees, and the community — improving customer satisfaction and employee engagement and strengthening the business’s reputation and long-term viability.

How to Think in Systems

Everything is connected to everything else. Time flows, cash flows, and so do many other things. When we think in systems, we see how outcomes emerge from relationships and interactions — like how a tiny seedling in a bottle turns into a beautiful array of self-sustaining life. Aside from creating your own closed-bottle terrarium at home (which honestly sounds like a lot of fun to me), here’s how you can get started thinking in systems:

Understand the Big Picture: Begin by stepping back to view the entire system rather than just its parts. Recognize how various elements within the organization and its external environment are connected. This holistic perspective helps identify how changes in one area can impact others.

Map the System: Use visual tools like flowcharts or system maps (like how we mapped the home heating system and lemonade stand) to illustrate the relationships between different components of the business. You can map processes, resources, information flows, and feedback loops. Visual representations help clarify complex interdependencies and can be a powerful tool for understanding, discussing, and iterating systems.

Identify Feedback Loops: Look for areas where actions lead to reactions that, in turn, influence further actions. Understanding both positive and negative feedback loops within your system can help you manage growth and stability more effectively.

Think in Scenarios: Since systems are dynamic and influenced by external variables, thinking in scenarios is beneficial. Consider different potential outcomes based on varying conditions and how they might affect the system. This approach can help anticipate challenges and identify where leverage points might exist that can drive significant impact.

Focus on Relationships, Not Just Elements: In systems thinking, the relationships between elements often hold more value than the individual parts themselves. Pay attention to how elements interact, communicate, and influence each other, and consider how you can design these interactions to improve the system.

Embrace Iteration and Adaptability: Systems thinking is not a one-time effort but a continuous process of improvement. Embrace an iterative approach of prototyping ideas, testing changes, learning from them, and refining your system continuously.

By incorporating these steps into their strategic and operational thinking, business designers can leverage systems thinking to create more sustainable, efficient, and adaptive organizations. Thinking in business systems will enhance internal processes and customer engagement and create long-term success and innovation.

Sam Aquillano is an entrepreneur, design leader, writer, and founder of Design Museum Everywhere. This post was originally published in Sam’s twice-monthly newsletter for the creative-business-curious, Business Design School. Check out Sam’s book, Adventures in Disruption: How to Start, Survive, and Succeed as a Creative Entrepreneur.