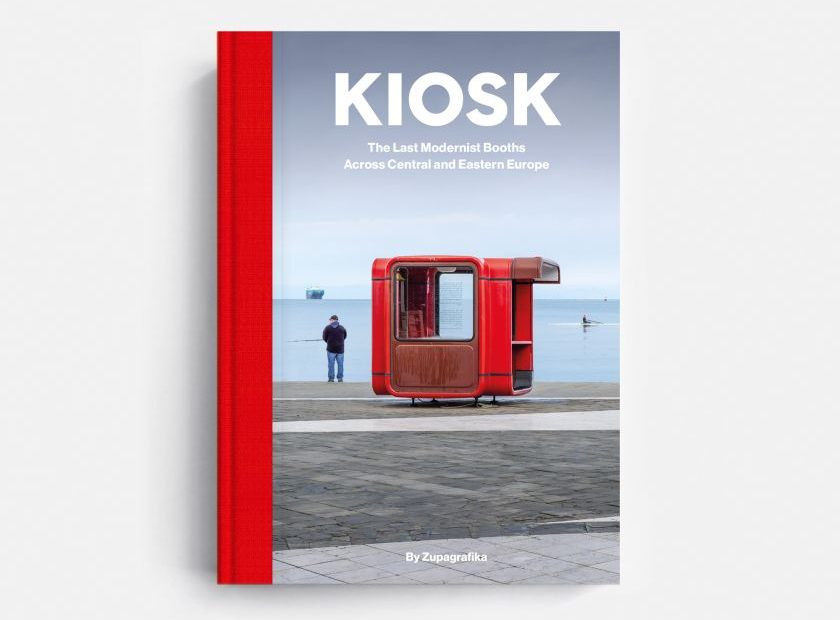

This striking new volume by Zupagrafika chronicles vanishing Soviet-era kiosk designs across the ex-Soviet world.

In cities across formerly communist Central and Eastern Europe, a distinct type of small modernist architecture is slowly vanishing from the urban landscape. Soviet-era kiosks – tiny, modular booths that served everything from hot dogs to newspapers to currency exchange – were once a ubiquitous sight from Warsaw to Belgrade. However, many were abandoned or demolished after the fall of the Eastern Bloc in the 1990s.

Now, the publishing team of Zupagrafika, aka photographer David Navarro and writer Martyna Sobe, have chronicled these fading kiosk structures in a striking new book, Kiosk: The Last Modernist Booths Across Central and Eastern Europe.

With over 150 photographs taken over the course of the last decade, from Ljubljana to Warsaw and from Belgrade to Berlin, this lovingly produced tome documents the remaining examples of these compact buildings before they disappear completely from the world.

The book includes a foreword by urban explorer Maciej Czarnecki and an introduction by architectural historian Anna Cymer, offering invaluable insights into the history of these mobile structures.

Intricate urban elements

“For the last ten years, our focus has been on capturing images of residential neighbourhoods, mainly within the countries of the former Eastern Bloc,” the duo explain. “Yet, our curiosity extends beyond mere architecture to the intricate urban elements embedded within these landscapes. Our penchant for collecting unique objects, such as kiosks, has culminated in the perfect opportunity to compile them into a book.”

The origins of these mass-produced kiosks date back to 1966 when Slovenian architect Saša J. Mächtig designed the seminal K67 model. Its modular design, made from innovative materials like plastic, allowed the K67 and similar kiosk systems to be flexibly deployed across the Soviet sphere.

In the following decades, variants such as the Polish Kami, Macedonian KC190 and Soviet Bathyscaphe sprouted up everywhere, from city plazas to housing estates.

A refreshing breeze

While highly functional, the kiosks’ sleek styling brought a “refreshing breeze of modernity and variety” to the often dreary architecture of communist cities, writes architectural historian Anna Cymer in the book’s introduction. Despite their small scale, the kiosks took on an outsized social role as micro public spaces fostering new interactions.

After 1989, many kiosks were privatised, and their new capitalist owners personalised them with hand-painted signs and decorations, giving each one a unique character. But age and competition from larger businesses took their toll. While some remain in operation today, many more have been closed, stripped of their innards, or reduced to crumbling shells.

In fascinating contrast, David’s photographs capture both the miraculously preserved and utterly decaying examples of these space-age structures.

“Each kiosk shown in the book has its own charm,” he says. “Those that have undergone renovation, such as the Kioski café in Berlin, housed in the yellow second-generation K67, indicate the timelessness and universality of Saša J. Mächtig’s concept. On the other hand, the destruction of some kiosks is also fascinating; many of them remain functional despite decades passing. Additionally, the typography, graphics, signs, and other elements added by the owners give each booth a unique character.”

Last of the owners

Throughout their obsessive documentation, Zupagrafika frequently encountered and interviewed the last proprietors of these fading kiosks. They share amusing anecdotes in the book about owners’ taking pride in booths they’ve maintained for decades while enduring scorching summers and freezing winters alike.

In this sense, this book operates as both a celebration of modernist design and architecture but also a bittersweet eulogy for a disappearing part of Eurasian urban life. As Anna reflects, the demise of these kiosks’ represents “the end of an important social and cultural phenomenon that cannot be replaced or reconstructed”.

With gorgeous imagery printed on high-quality paper stock, this impressive volume by Zupagrafika preserves the legacy of these unique structures before they’re gone forever. It’s a must-have for fans of Brutalist and Soviet-era architecture, urban history buffs, or anyone enchanted by the charm of these utilitarian cultural relics.