In 1800, the cotton industry was firmly entrenched in Manchester, England. Cotton was imported from, among other parts of the globe, the American South, where the trade was dependent almost entirely on slave labor. Colonization, and all that it entailed, was a major cog in the supply chain that stocked the “merchant exporters” with unprocessed material from which textiles were made into consumable fabrics.

The wealth that cotton brought to England cannot be overstated. Manchester boomed during the 19th century and a warehouse district was created where small independent merchants sprouted like cotton buds. This necessitated some form of visual distinction or identification for the many businesses.

Trademarks have existed in many forms since 5000 BC, but the first legal infringement action in England regarding any type of trademark “was a dispute over one which was copied and applied to a piece of inferior cloth in order to increase its value,” writes Adrian Wilson, collector and scholar of vintage textile labels and tickets. (Wilson’s website www.textiletrademarks.com shows many examples.)

Per a 1618 case, Southern v. How: “An action upon the case was brought in the Common Pleas by a clothier, that whereas he had gained great reputation for his making of his cloth, by reason whereof he had great utterance to his great benefit and profit, and that he used to set his mark to his cloth, whereby it should be known to be his cloth: and another clothier perceiving it, used the same mark to his ill-made cloth on purpose to deceive him, and it was resolved that the action did well lie.”

Another report stated, “A clothier of Gloucestershire sold very good cloth, so that in London if they saw any cloth of his mark, they would buy it without searching thereof; and another who made ill cloths put his mark upon it without his privity; and an action upon the case was brought by him who bought the cloth, for this deceit; and adjudged maintainable.”

Fabric was always sold in pieces, not rolls. A factory would provide the merchant with long lengths of finished cloth, which he then folded into shorter pieces with a plaiting machine. Each piece had to be clearly stamped or labeled with the supplier’s mark and the cloth’s type and length, creating a faceplait. The pieces were then wrapped in protective hessian and compressed into a bale, ready for shipping to the final customer. The distinctive marks not only acted as recognizable brands to attract a customer, they also enabled the merchant or seller to be easily traced following any kind of dispute.

Faceplaits were created in the “making-up” departments of cloth manufacturers and finishers (especially bleachers), or in merchants’ warehouses. A drapery store would know the exact length and width that would yield enough cloth for, say, six dresses for a tailor customer and would order various patterns of the same piece size. The same would go for importers of cloth for saris, turbans and any other of the thousands of uses cotton was put to in markets around the world.

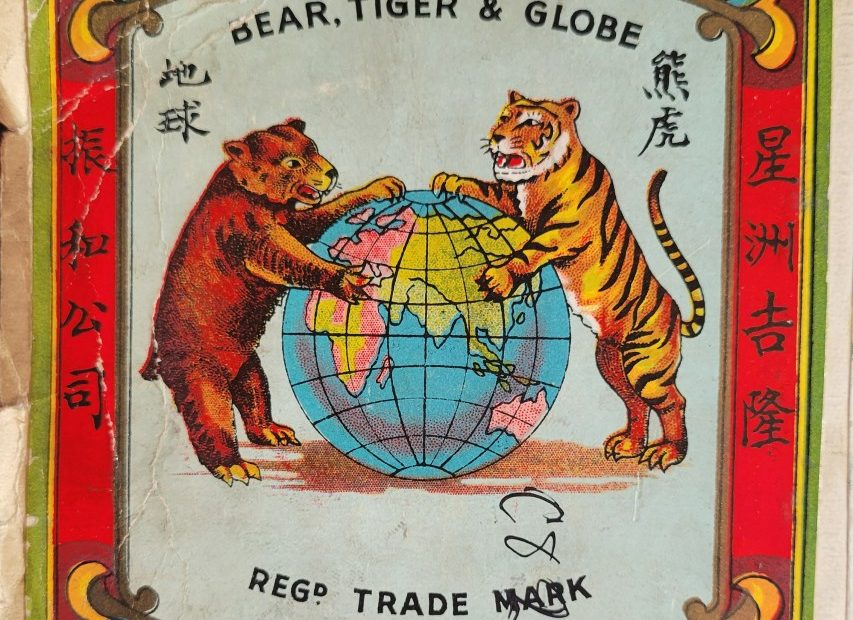

When trademark registration was introduced in the 1870s, it took a specialist office 10 years before they worked through more than 100,000 designs that had been put forward. Today, 450 huge volumes of registered textile trademarks exist in the National Records in Britain—visually depicting thousands of religious scenes, indigenous tribes, places and even fonts that no longer exist.

Per Wilson, this was probably the largest campaign ever seen where the customers’ culture was an integral part of the marketing. He adds, “Of course, there are many terrible parts of colonialism, and one of the reasons that this story has been passed over is due to the fear of being accused of saying there was something positive about Manchester’s cotton trade—but ultimately, like Amazon or goods made in China, people bought Manchester fabric because it was the best quality for the price.” And also, because the merchants who sold it in markets across the world knew it was better to appeal to the locals than just slap a global logo on the goods.

Original ticket painted by anonymous hand.