One of the book ideas I’m considering is a history of shopping in retail markets (i.e., through one or more intermediaries, not the direct producer). It would begin in roughly the 17th century and take an international perspective to permit comparisons.

Unlike my previous related work in The Substance of Style and The Power of Glamour, this book wouldn’t focus primarily on consumer motivations but on social interactions. Shopping blurs the public and private. It’s an everyday arena in which people interact, directly and indirectly, with strangers. As a result, the customs, conventions, mores, and institutions that evolve as we shop express—and in some cases change—how cultures address fundamental social questions. These include norms of equality and respect, expectations of safety and comfort, and boundaries of credit and trust.

I haven’t yet written a full-blown proposal, although I’ve done a sort of pre-proposal outline because I haven’t yet decided whether this project will work. Before the 19th century, it’s hard to get documentation on what the experience of shopping was like, as opposed to what people bought or owned. (Historians of consumption do a great job of mining probate inventories and criminal cases.) Yet the roots of modern shopping are in the 17th century.

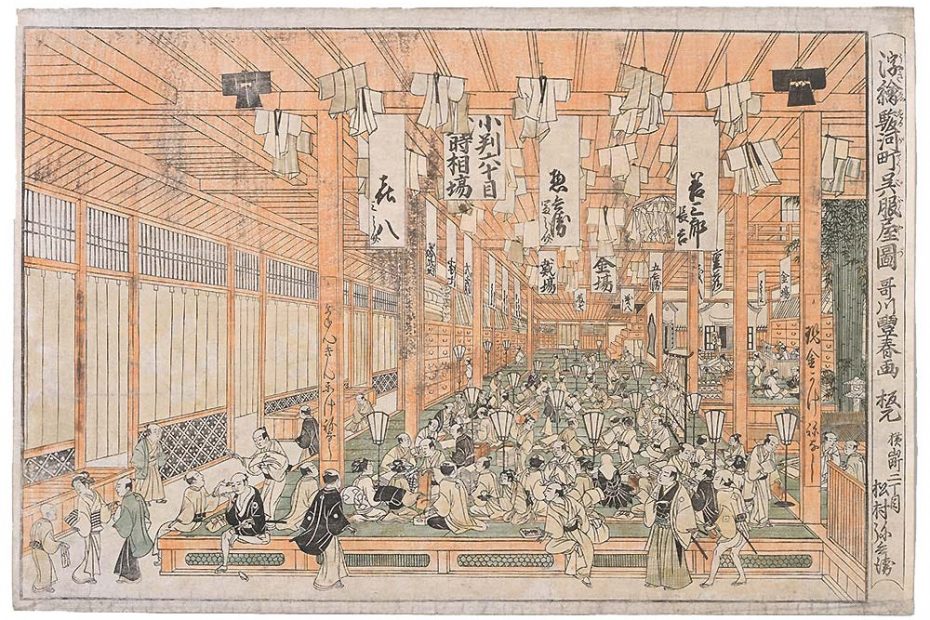

Interior of Mitsui Echigoya in Surugocho, the world’s oldest department store, by Utagawa Toyoharu, 1768. Source: Wikimedia

Mitsui Hachirobei Takatoshi founded the world’s oldest department store around 1673! He was quite an innovator. He introduced single prices (no haggling) and cash-only purchases. Instead of concentrating on fickle aristocrats who paid up only twice a year, he concentrated on selling to commoners, who were becoming increasingly affluent. He sold cloth wholesale to smaller provincial stores at a modest markup, allowing him to stock greater variety. He opened branches in Kyoto and Osaka, creating a small chain. Rather than the standard lengths used for kimono, the store sold cloth in whatever length a customer wanted—but at a higher price per unit.

“They sell velvet by one-inch squares, brocade large enough to make a tweezer case, or red satin enough to cover s spear insignia,” wrote the novelist Ihara Saikaku in 1688 (translation by John G. Roberts in Mitsui, from which I take this information.) By 1700, his store was the largest in Japan. “To look at the shop owner, he appears no different from others, with his eyes, nose, and limbs in the usual arrangement,” wrote Saikaku. “This is an example of a really big merchant.”

The store has evolved—and it formed the basis for a much larger banking and industrial empire—but it’s still in Tokyo today, as the Mitsukoshi department store.

Virginia Postrel is a writer with a particular interest in the intersection of commerce, culture, and technology. Author of “The Future and Its Enemies,” “The Substance of Style,” “The Power of Glamour,” and, most recently, “The Fabric of Civilization.” This essay was part of a larger essay originally published in Virginia’s newsletter on Substack.

Header image: Exterior view by Utagawa Hiroshige. Source: Wikimedia