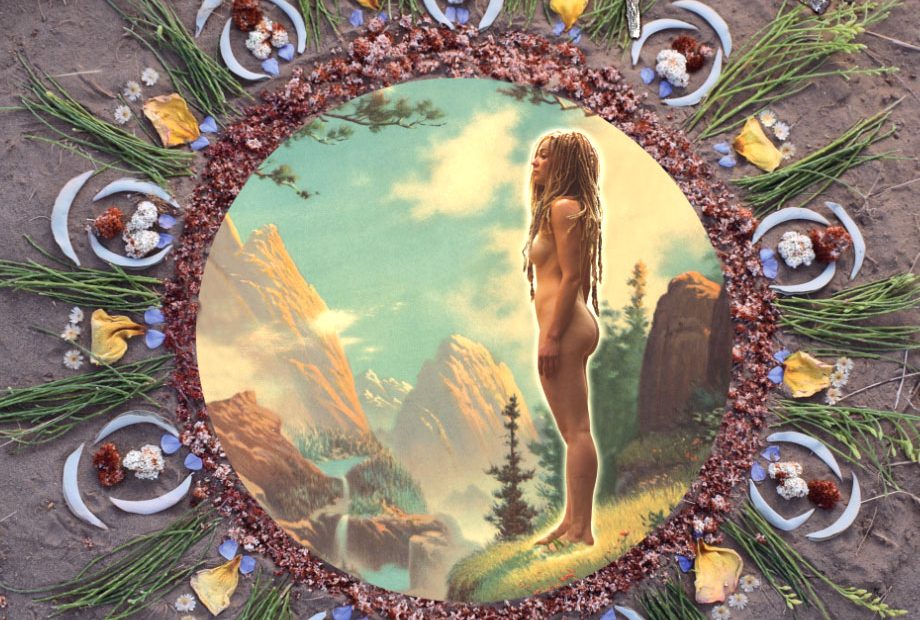

The blurb on the back cover of Zavier L. Cabarga’s Wild Girl: Wilhemina of the River Bottom and Other Tales 1897–2027 says it all: “Wild Girl is a hand-drawn and photographic graphic novel like no other: It’s graphic and it’s novel!” It is also epic in its scope and high in production, drawn from the unbridled imagination of a veteran graphic design performer. At the height of his comic prowess, Cabarga imagines a mythic woman living in the woods, whose legend, heretofore forgotten, he brings to life through a series of pastiche parodies of tropes and genres spanning the late 19th century to the digital 21st. In this exchange we discuss the untold truth about the most ambitious creative outpouring of Cabarga’s lifetime.

We have a long history. I knew you when you were, I think, 15, and you were about to publish a legit monograph on the Max Fleischer animation studios. Next, I hired you to be my assistant art director at ROCK magazine. Still in your teens, you created many things for me, including custom lettering for my first published book, three covers for later books, dozens of illustrations for The New York Times Book Review, and a lot of other things that I’m forgetting. Somehow you had an ability to recreate every graphic style of the late 19th through the early 21st century. How did you achieve mastery of form at such a young age?

Thanks, Steve. You were a precocious lad yourself! The thing I remember about doing layouts with you in the offices at ROCK was singing doo-wop harmonies as we worked together. No one ever told us to shut up, so I think we weren’t too bad! I grew up the son of an art director who went into Manhattan every day to work for the great cartoonist Will Eisner, who owned a small ad agency by then. My father never really instructed me in design, I just saw him doing paste-ups and sort of took it for granted I could do it too. When I was 12, he hired me to cut amberlith color separations for his publications. My friends would come by and say, “Let’s go bike riding,” and I’d say, “Naw, I gotta do color-seps.” And I pretty much never stopped working since then. I mean, it was volitional; that’s what I wanted to do with my life! Typically, illustrators develop a personal style. I just wanted to try every style—I loved vintage design.

Well, we’re not here to talk about past glories, but rather your latest book, Wild Girl: Wilhelmina of the River Bottom and Other Tales 1897–2027. How did this convincingly detailed pastiche of vintage graphics and narrative come together?

I think Wild Girl has been the culmination of many book and illustration projects I’ve done through the years. And it brought together all the vintage-style graphics that I’ve always emulated. But the book started out as a notion, just a funny idea for a photo shoot that would be a spoof on the documentary My Octopus Teacher. Instead of an octopus, a burned-out photographer goes into the woods and meets a wild girl. I didn’t even know at the beginning it’d become a book, and the octopus idea became irrelevant. I wanted it to become a French film because I thought they would accept the innocence of the naked gamine in nature. But I’m not a filmmaker.

You play a character, Milton, in a “film” story about tracking Wilhemina. What about her is so compelling and emotional for you? In short, who is this Wild Girl and what does she mean to you?

Wild Girl was almost entirely photographed in Ojai, CA, a beautiful little bucolic town between Los Angeles and Santa Barbara. We have this nature preserve with hiking trails and a lovely river running through it. This is where I came up with the initial Wild Girl story, which I then claim to be a documentary. There is this one wooden bench in the Preserve placed in memory of a benefactor named Milton, so my character—the burned-out lingerie photographer who follows the “call of the wild; the call of nature”—became Milton Benchmohr. In the story, Milton discovers he is, incredibly, Wilhemina’s father, but he can’t explain that to her because she was abandoned at birth by her mother and really doesn’t speak.

You ask, what does this Wild Girl mean to me? You know, we here in Ojai are all about self-realization and introspection, but I’ll be darned if I can answer your question. But maybe it’s got to do with me learning to love nature at the river bottom—since I spent my whole life at a drawing table. And I’m sure there’s a subconscious reason I’m an actor in three of the stories—aside from my services being free—but I guess sometimes an artist just throws himself into his work.

One of the “stories” in the book is done to replicate a 1924 German silent movie. You play the role of the photographer who finds the Wild Girl in the forest, and a Zookeeper.

Once the first story was done I realized it wasn’t long enough for a book. So I came up with the “German” version, “Wilhemina das Wilde Fräulein.” As you recall, Steve, one of my first books in the1980s was A Treasury of German Trademarks (1985), about pre-war German trademark design. Those amazingly modern logos helped influence our present computer icons. So, I am a “German-o-file” for sure! For this story in the book I made a blackletter font for the silent film titles, and had a ball super-imposing my photos of the Wilde Fräulein over scans of decaying 35mm nitrate film strips. I play the pet photographer who first encounters the Wild Girl, but the “insane zookeeper” was actually acted by a friend who was in the process of transitioning into a woman. She agreed to cross-dress back into a man for the role. I had to Photoshop out her nail polish.

… After I created the German Fräulein story, I started thinking I should cover the entire chronology of the Legend of Wilhemina (I was just having so much fun making these stories!). I wanted a spread of stories through the years, and that was really when the project started to take form as a book. The Yellow Kid spoof, where we meet his country cousin Pink Willy, became the earliest story, 1897, and I drew that one entirely. It might interest you, Steve, that I scanned some mezzotint Benday screens printed on acetate, that I once bought from a long-defunct art supply store off Madison Avenue, to create the color

overlays for Pink Willy in imitation of the screens they used in the 1890s (rather than the straight-up aligned Benday halftones that later became standard in printing).

You also produce a pitch-perfect remix of Fleischer’s Betty Boop as Wild Girl in a take-off of an early sound cartoon. You’ve always been a Fleischer fan—is this one of the drivers of this book?

Really, I don’t know how I come up with this stuff. Not only is it Betty Boop as a Wild Girl raised by pigeons, but she’s also a communist who saves Prospect Park in Brooklyn from being turned into an “elitist bowling alley” by Wall Street developers.

It was fun to adapt Betty into a Wild Girl since for years I painted dozens of standard Boop greeting cards and other products. The thing about this book is it’s been the most drawing I’ve done in almost 30 years! My Wikipedia page says, “By the early 1980s Cabarga had become one of the most popular illustrators in New York” (thanks in part to your assignments, Steve). But I came to realize I’d always been a bit lazy in my art—often not working sufficiently to perfect the drawings—so I tried to make up for it in this book. I just didn’t want to look back and go, “Darn it, why didn’t I improve that crappy anatomy!”

Tell me about the inspiration for the “I Dream of Wilhemina” TV show.

“I Dream o’ Wilhemina” was another attempt to fill in a 1960s chronological gap in the book contents. All the stories in Wild Girl have this apocryphal aspect—like, doesn’t everybody remember this TV sitcom? The fact that there’s this Wild Girl, who gets displaced from the forest setting where she’s lived all her life, who runs around naked and nobody cares, is just part of the absurdity of it. I scanned images from an old interior design book from the 1960s to create the living room and office interiors in this story. Of course, I did my research too, by watching old sitcoms.

Throughout the book, bespoke lettering and distinctive storytelling come together in such a way that they beg the question: How long did you work on the contents of this design-driven project?

Thanks for mentioning that. The theme of my earlier book, Logo, Font & Lettering Bible (2004), is “Why use other people’s fonts when you can draw your own?” That’s one of the treats of Wild Girl: It’s full of original, custom lettering and logos—because I can! And I think that definitely adds to the authentic vintage feel of the project. You know, in the old days when you needed headline type you didn’t select a font, you hired a letterer. Wild Girl evolved over four years, and since there was no deadline, I could just keep adding more “value” to each story; they all went through several iterations. I’ve authored many books on graphic design, but in recent years they started becoming funny as well as instructional—some Amazon reviewers have actually acknowledged the humor. And I think the storytelling style you refer to is part of that evolution for me. My writing style is somewhat mannered, too.

What was the budget for the production?

It kind of amazes me, but other than fees for the models, most of the actors were friends, and settings included friends’ living rooms, cars and studios—and mainly the great outdoors. I bought various wigs, nerdy glasses, lab coats from Amazon, each around 20 bucks. I sewed a raggedy leather costume for one of the girls, the Zookeper’s hat I made from a faux leather pencil case, and I built a wooden box to which were pasted the printed sides of a vintage-looking camera. It looks pretty convincing! And of course, everything else needed I created in Photoshop. As an illustrator I was able to literally draw whatever was lacking for a scene. The last story in the book, “Wilderella of the Necronet,” I’m most proud of. She’s a beautiful robot whose programmed Artificial Intelligence skews toward goodness and ethics, and she ends up conquering the world with love. The story was shot against a green screen, and then I dropped in futuristic digital backgrounds. Silhouetting the figures, even with the green screen, was still hell!

So, where can we pick up a copy of this wild tome, this magnum opus of yours?

Well, it’s not on Amazon yet, but it is on Ebay. And you can contact me at lesliecabarga.com. The cost is $32 postage-paid, which is a deal! Naturally, I’ll sign the books upon request.

The post The Daily Heller: The Legend of Wilhemina das Wilde Fräulein appeared first on PRINT Magazine.