The Emotional Evolution of Typography

Utopia traditionally refers to an idealized society, but in typography, type utopia represents the frenzied intersection of form, function, and emotion—where letterforms communicate with clarity, impact, and innovation. However, this “utopia” isn’t about perfection but rather the evident tension between rebellion and idealism.

Rebellion in type means breaking with tradition—challenging conventions and embracing unpredictability, as seen in the radical shifts of movements like Dadaism or Bauhaus. Idealism is the drive to push design towards clarity and beauty, creating type that is both functional and expressive.

The hands of self-determined designers have been caked in the primordial mud of Modernism since 1920 when Walter Gropius revised the radically welcoming admissions policy of the Bauhaus School. “For the foreseeable future, only women of extraordinary talents would be accepted,” he declared. Still, these creatives found space to experiment with abandon.

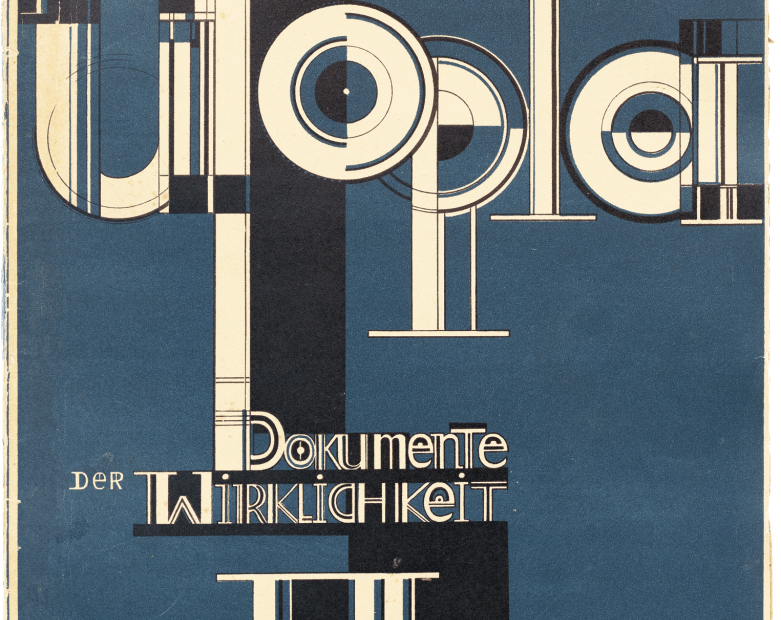

Utopia, Friedl Dicker and Johannes Itten, (Cover by Margit Téry-Adler), Bauhaus School, 1921.

Of note, Friedl Dicker’s collaboration with Johannes Itten on the type-focused publication Utopia reveals a rarely seen, gestural side of the Bauhaus. Her compositions are stunning improvisations, blending Blackletter and Roman type families: from Unger-Fractr, Fette Gotisch, Normande, Tiemann-Medieval, and Bernhard-Antiqua. Through her precise yet dynamic layouts, Dicker brings Itten’s essays to life, merging dense, chaotic hand-lettering with bold, expressive design.

Pages from Utopia, Friedl Dicker and Johannes Itten, Bauhaus School, 1921.

As typography marches towards its utopian future, the flexibility of digital design expands possibilities for creativity, drawing from the experimental spirit of the early 20th century—when Dadaists, Futurists, and Constructivists disrupted visual language. New type disruptions explore anarchic layouts, emotive forms, and evolving mediums.

Breathing New Life into Typography: Anarchy + Archival Experiments

Chantal Jahchan, an independent designer based in Brooklyn, blends experimentation with idealistic pursuits of beauty and meaning. Her work adapts to today’s fragmented, fast-paced media landscape. Known for her narrative illustrations, Jahchan integrates archival imagery, hand-drawn elements, and manipulated type to create illustrations for book covers, and publications like The New York Times, The Atlantic, The Economist, The BAFFLER, and The New Yorker.

While she refers to herself as “a graphic person,” her process is rooted in past artistic traditions of Marcel Duchamp’s readymades, Robert Rauschenberg’s combines, and John Baldessari’s adaptations of found photography.

Left: Untitled [Mona Lisa] by Robert Rauschenberg, ca. 1952, Engravings, printed paper, fabric, paper, graphite and foil paper on paper; Right: Factum I, 1957, by Robert Rauschenberg; Combine: oil, ink, graphite, crayon, paper, fabric, newsprint, printed reproductions, and printed paper on canvas

Rauschenberg said, “A newspaper that you’re not reading can be used for anything,” and saw the world outside his window as one big painting. Likewise, Jahchan’s sources are universally accessible: Wikipedia and archival material.

After cutting her teeth at Pentagram under the guidance of the iconic Michael Beirut and working at Order alongside Jesse Reed, Jahchan began a budding independent practice with an invitation from Devin Washburn of No Ideas to create a cover for Verso Books.

Despite her perfectionism, it was freeing to say yes. “What’s the worst case? It’s an ugly book cover and you don’t have to put it on Instagram.” With that, How to Blow Up a Pipeline (Andreas Malm) features neat bento boxes of bucolic landscapes juxtaposed with barbed wire and fencing, organized in a grid around the type, set in Nick Sherman’s version of Franklin Gothic, but tweaked with blobby, slightly imperfect ink traps that give it a vintage feel. “I was looking at old how-to manuals,” she says. “I got lucky with such a good title; don’t fumble that!” The cover was hardly a fumble; the design made the NYT: Best Book Covers of 2021 and the AIGA 50 Books 50 Covers 2021.

That led to a waterfall of new assignments dealing with heavy topics and complexity – all on a tight timeline. She explains, “One of the things that drew me to this world of editorial illustration is how quick yet complete each project is. You represent it and it goes out into the world.”

For Jahchan, archival imagery lends itself to serious or academic subject matter. For Acacia Magazine, she illustrated the Editor’s Letter on Palestine. “I love to use text as a texture. There was an Arabic poem that was quoted in the piece. I had my mom write in Arabic script and scanned that in.” It’s layered within silhouettes of children, which are half poetry, half photograph.

Filling in pieces is key when working with what Jahchan calls “precious, raw archival material.”

For “I Still Believe in the Power of Sexual Freedom,” a New York Times Opinion piece, she blended collage, found imagery, and created her own data visualization based on one line: And in order to dissolve stereotypes, we need to replace them with a constellation of women’s realities, which includes our sexual desires. Her solution? “Let’s put the different types of sex into a little constellation,” she explained. “That’s not something you’ll find on Wikipedia.”

Her designs are like a verbal puzzle that guides the viewer, with some text being found and some being digitally typeset and manipulated. Like the printing process, it takes a lot for her type to exist. In the New York Times Magazine’s “Why Corruption Is So Hard to Prosecute in the U.S.,” there were several colons in a red strip leading nowhere because she removed them. On the other hand, the list of dollar amounts she made from scratch to match the original text. “I typeset those in Times New Roman then put effects on it,” she confesses.

Jahchan did the same for “What Trump Means When He Tells Us to ‘Fight’” (NYT Opinion), explaining that “These different images were from different sources; to make them all look like they’re from the same source, I treated them with a halftone and desaturated print effect.” The result looks like newspaper cut-outs with the word ‘fight” underlined in pencil. Jahchan spends a lot of time faking printed things, like a skilled forger. She puts blurs on letterforms to simulate ink pooling in the traps and wave effects to create the fibers of newsprint.

Often, the archival imagery is gold, like in the illustration for The Atlantic’s “The West Is Returning Priceless African Art to a Single Nigerian Citizen,” where the beauty lies in the intriguing composition laced with artifacts and found British stamps. “This is a moment where the archival imagery really shined on its own.”

Her graphic storytelling is bridging a poignant moment of type that idealizes printed matter and tactile textures while blurring the lines between what’s found and what’s generated. “It’s freeing to make it yourself when you can’t find it,” she concludes.

Baldessari claimed, “What the artist does is jump-start your mind and make you see something fresh, as if you were a visitor to the moon.” This is the spirit Jahchan chases.

It’s interesting how these little moments sneak into the piece but it’s just by having collected them and putting them on the same page. That is its own story.

Chantal Jahchan

Left: Seashells/Tridents/Frames, 1988, by John Baldessari; Right: Umbrella (Orange): With Figure and Ball (Blue, Green), 2004 by John Baldessari

All imagery courtesy of Chantal Jahchan except where otherwise noted.

The Age of Emotional Typography: Expanding Our Expressions

Typography is the voice of design, emoting cues beyond the aesthetic. Jessica Walsh has long championed the power of emotion in design, making it a tenet at &Walsh, her NYC creative agency. Her early days as an Art Director at PRINT Magazine during the 2008 financial crisis, allowed her to explore tactile techniques like body painting that built the foundations of her meticulous craft.

Never shying away from the raw reality of the human experience, her personal projects like 40 Days of Dating, 12 Kinds of Kindness, and Let’s Talk about Mental Health, bring human emotions to center stage. She has since created alchemy with these conceptual explorations, infusing brands like Plenty and Coconut Cult with the extremes of human experience.

Consistently seeking to elicit a feeling is her edge. “We’ve seen that the most successful brands stand for who they are unapologetically,” she notes. “A great brand is like a great person: true and honest about who they are, and unafraid to show their true colors. Figuring out how to be more human in the way you act and engage with your audience is a foundational step in building trust.”

Typography is such a powerful way to reflect the human experience.

Jessica Walsh

In 2024 Walsh launched “Type of Feeling,” a foundry dedicated to capturing emotional depth within typography. “The right type can make people feel vulnerable, uncomfortable, or even uneasy—and that’s where the magic happens,” Walsh explains. To that end, the foundry debuted with eight distinct typefaces. Meraki evokes artistic devotion with its warm, welcoming human serifs. Ssonder emits quiet authentic connections with stylized ligatures and unexpected letterform proportions. Walsh points to Onsra, a typeface designed to capture the bittersweet feeling of longing for something that cannot be returned. “The balance of normal-width and double-wide letters together with the exaggerated tail of the Q all capture this sense of reaching and breathing slowly in and out.” And for joyful celebration, Jubel‘s thick bold strokes meet animated curves.

Type of Feeling reflects Walsh’s studied type knowledge and emotional intelligence. The current offerings are ready-made but rooted in career-long research. With plans to expand the foundry’s offerings, Walsh captures their inherent strength: “We tried to give these feelings an identity by building them directly into different elements of the typeface.”

While emotional typography has surged in recent decades, its roots extend far deeper than the 90s, which is often cited as the era of expressive branding with designers like David Carson and Brent Rollins. Emotional type has evolved alongside cultural shifts, from the exuberance of Art Nouveau to the stark modernism of the Bauhaus, and later to the rebellious experimentation of the 70s and 80s. “Milton Glaser’s Baby Teeth from 1968 is a standout for me,” Walsh notes. “With its bold, geometric forms and unapologetically playful design, it captures the rebellious spirit of the counter-culture movement. This typeface proves that design can balance seriousness with fun.”

Left: David Carson, Ray Gun Cover—Oasis, 1998; Right: Brent Rollins, Blackstar Album Cover, 1998

The pendulum of typography historically swings between functional minimalism and expressive ornamentation. The stark efficiency of Bauhaus-era type gave way to the vibrant, illustrative lettering of the 70s, only for tech-driven digital typography to once again prioritize utility. “While the present focus is on emotive and human-centric type,” Walsh reflects, “it’s likely that we’ll eventually see a counter-movement towards functionality, utility, or even something we can’t pinpoint today.”

Emotion is unlikely to disappear entirely from type, particularly as the need for human connection intensifies in an era of AI-generated content. Walsh sees brands increasingly embracing complexity, moving beyond traditionally safe, polished messaging.

No emotion has been ruled out for us: we think each poses a unique perspective on a future typeface. Even negative emotions are part of our humanity and should be felt, and therefore reflected in our collection. The more complex the emotion, the better!

Jessica Walsh

While commercial design often gravitates toward positive emotions, Walsh believes there is room for a wider spectrum of human experience. “Too often brands are told to suppress idiosyncrasies out of fear of how consumers will respond,” she says. “The problem is that when you try to please everyone and avoid anything that might offend someone, you wind up with a ‘vanilla’ brand that says nothing.” She points to projects like TED’s Countdown, where typography was deliberately chosen to evoke urgency and inspire action on climate change.

As technology advances, so too does the frontier of type exploration. While AI-generated designs are improving rapidly, Walsh envisions a renewed appreciation for the human touch in type design. “AI is a clear new frontier for all creative workflows—but while we can’t ignore AI, I think it will lead to a renaissance in human-led designs,” she says. “I’m excited for a new wave of designers that bring a little bit of David Carson to their work to counterbalance streamlined and perfect AI-led designs.”

Ultimately, typography is a vessel for emotion, a means of communication that transcends words. As Walsh puts it, “Typography is one of the most powerful tools we have to make people feel something. And in a world oversaturated with content, that ability to connect on a deeper level is more important than ever.”

All imagery courtesy of &Walsh except where otherwise noted.

Risk + Revolution: A Design Philosophy Forged in Uncertainty

In an age defined by global uncertainty, How&How’s founding in 2020 during the early days of the pandemic was an act of rebellion. Married co-founders Cat and Roger How chose to embrace the chaos as an opportunity to forge something fresh. In a world where “there is never a good time to have a baby,” they launched a family and design studio amidst the peak of a global crisis. That might seem counterintuitive. Yet, as Cat How reflects, their approach to business has always been rooted in the idea of “running towards the pain.” It’s this spirit of embracing the unknown, of resisting the comfort of the conventional, that defines them.

We approach every project wanting to jump into the unknown—to us it’s the only way of creating something truly unique.

Cat How

The studio, based in London and Los Angeles, actively rejects the safe, predictable options in favor of the bold, the unique, and the unfamiliar. This idealism is not naive, but rather a well-calculated philosophy rooted in the belief that only by embracing risk can one create work that resonates and stands apart. Every project becomes an opportunity to explore uncharted territories—be it understanding the cultural nuances of a Japanese AI-driven perfume brand or creating a rebrand that represents a zoo’s conservation mission.

How&How’s journey through design pushes the boundaries of what is expected in type and visual systems, embracing uncertainty as fuel for creative revolution. With Chester Zoo, the collaboration was grounded in this very idealism. How credits the marketing managers Kath Mainprize and Helen Dean for their openness to experimentation and their desire to make bold decisions. “They were clearly in love with the Zoo itself but had enough perspective and professionalism to know when to make brave calls,” she shares. This idealism and willingness to push for the uncharted made way for a progressive type treatment. Customized with Sharp Type, it takes a new twist on a Grotesk, bringing it to life with cues from nature: leaves, tails, and claws.

Together, the design vividly captures the Zoo’s proclivity for positive momentum in conservation. The iconic “C,” a form reminiscent of a rhinoceros horn, symbolizes the Zoo’s history of supporting endangered species and their constant fight for conservation. “The C actually came about in parallel with us developing the custom typeface,” How says. “We knew they needed their own typeface, so worked with Lucas Sharp to modify Sharp Grotesk to make it more animalistic, and bring in the movement from the brand idea ‘Force for Nature.’” The rebellious act here is not just in creating something entirely unique but in challenging what zoo branding had previously been, offering a design language that was unconventional, visceral, and brimming with movement.

This idealism isn’t confined to visual aesthetics but extends deeply into how her team approaches their clients and projects. They don’t just create logos or identities—they build narratives, dive into unmapped cultural territories, and aim to represent their clients in ways they couldn’t have imagined themselves. This philosophy drives How&How’s commitment to ownable type—to create identities that speak with originality and authenticity, unafraid to challenge industry norms.

The studio’s commitment to motion drives their work in an era when static design often feels inert and disconnected. How explains, “Motion is just another way of bringing a brand to life, and helping to visually communicate it better.” In the case of Chester Zoo, motion was used not only to bring energy and vitality to the brand but to represent the very behaviors of the animals it aims to protect—“swarming, flocking or herding,” as she notes.

Designers must now experiment with how typography flows and interacts with other elements—such as imagery, video, and texture—while considering the fragmented way in which audiences consume information.

Integral to How&How is the belief that design research isn’t just about solving problems but immersing oneself in a client’s story. How views research as an act of rebellion against the surface-level understanding of a brand. “We always interrogate and research all our projects meticulously,” How shares. Her team’s exploration of Aruba’s cultural symbols during their work for the Aruba Conservation Foundation shows how this research can ignite new ideas. The ornamentation of Aruba’s homes became the foundation for modular illustrations—something as unique as it is meaningful. This is idealism in action: not only honoring the culture but allowing it to shape the identity of a brand.

More than just a functional element of a brand’s visual language, customization is the ultimate act of ownership, an expression of a brand’s story that is both unique and intimately tied to its identity. “Custom type is always the dream. It’s one of the most fundamental ways we can fully integrate a brand’s narrative into every element of the design system,” How says. This rebels against generic, off-the-shelf fonts, much like Walsh’s Type of Feeling. Creating design that is as deeply personal as it is visually striking is typography’s new utopia.

All imagery courtesy of How&How.

Marching Towards Shangri-La

Typography has long surpassed being a functional tool—it evokes emotion, shapes perception, and connects us to our inner emotional world. In today’s design landscape, empowering brands to create authentic, resonant identities that speak directly to our inner world is the new big job. Rooted in the rebellious spirit of early 20th-century art movements and fueled by the pursuit of idealism, today’s designers must continue to challenge conventions and push toward new destinations.

Much like Shangri-La—an idyllic, unreachable paradise where harmony and beauty reside—the journey toward typographic utopia feels like an endless quest, a march toward something that remains just out of reach yet drives us forward. Designers forge ahead, creating new paths in the search for balance, where creativity, purpose, and emotion unite into an idealized form.

As the design world evolves, emotional typography will remain central, guiding brands through the complexities of technology and culture.

Through the ongoing fusion of rebellion and idealism, typography edges ever closer to its Shangri-La, a vibrant and dynamic visual language where art and communication coalesce in perfect harmony, shaping the future of visual storytelling.

In an era that echoes the politically dangerous times the Bauhaus and past design movements responded to, testing the structure of images and type language like the brilliant designers above is critical. Godspeed.

The post The 2025 Typography Report: A March Toward Utopia appeared first on PRINT Magazine.