The Red Scare lasted throughout the Cold War. It turned postwar Americans into a suspicious fear-driven society. This witch hunt’s agenda dated back to the 1920s, following the Russian Revolution that posed a threat to capitalist interests. Scare propaganda was meant to stem the Soviets’ purported widespread international influence by exposing communist travelers throughout American government, industry, education, society and the arts. The clear goal was to rid the nation of presumed fifth columnists by denying their livelihood and civil rights through accusations, libel and innuendo.

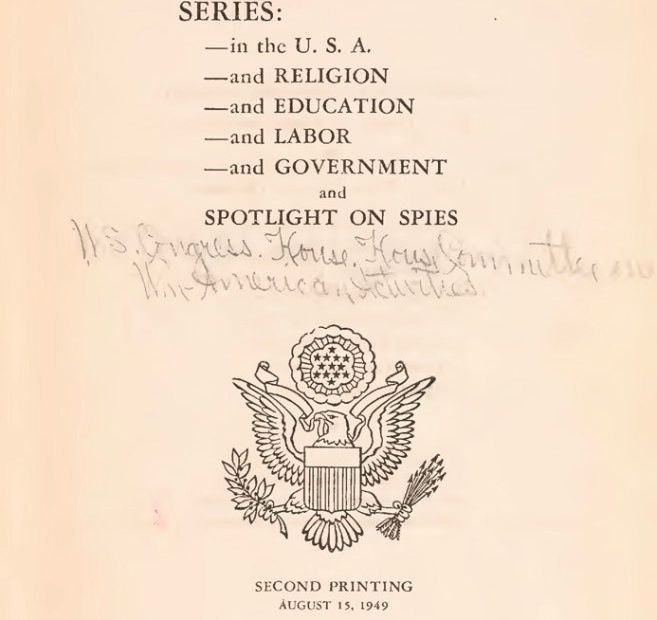

There was plenty of red meat for Congress’ House UnAmerican Activities Committee (HUAC). Individual lives were ruined by casual or prevaricated associations with “Communist front” organizations. Policing and investigating were not limited to Congress and the FBI, and self-appointed watchdog groups were established to provide incriminating data on US citizens. This was a period when poisonous “blacklists” were in force to keep potential undesirables (i.e., progressives and liberals) out of mainstream American life.

When I was in high school, I learned about “blacklists” from fellow students whose parents were directly impacted by the “committee.” Suspected of having ties to the Communist party, some of my friends’ parents were summoned to testify before HUAC investigators, who coerced witnesses to “name names” of fellow travelers. Those who refused to cooperate likely lost their jobs or were imprisoned.

New York City was one of many focal points for the Red Scare, and The New York Historical highlights the intersection of politics, art and culture that shaped America’s Red Scare in Blacklisted: An American Story, a traveling exhibit created by the Jewish Museum Milwaukee, on view in New York until April 16. The exhibition builds on the story of the Red Scare and the blacklisting of screenwriters and directors known as the Hollywood Ten, and the countless others who were impacted. Blacklisted captures the tensions of the domestic Cold War, revealing how global politics infiltrated America’s entertainment industry in the late 1940s and ’50s through a government crackdown on artistic expression.

The exhibition introduces the first Red Scare, which came on the heels of the First World War. Wartime heralded a crackdown on both immigrants and political dissidents, particularly critics of war. Hundreds of immigrant activists were deported, including Emma Goldman. A pamphlet she co-wrote in 1919, Deportation: Its Meanings and Menace; Last Message to the American People, is on display.

One of the most vulnerable groups of red-baiting and blacklist harassment was the entertainment industry, which often succumbed to pressure from self-styled anti-communists, who published a directory, Red Channels, listing hundreds of suspected communist sympathizers. It was a bible for producers, directors and others who colluded with extralegal destruction of careers. Objects on view include blacklisted screenwriter Dalton Trumbo’s Academy Awards for Roman Holiday—originally awarded only to co-writer Ian McLellan Hunter, since Trumbo was prohibited from working in film under his own name—and The Brave One, awarded to the fictitious Robert Rich. (Hunter was later blacklisted, too.) Also on display are typewriter ribbon tins with personal items Trumbo collected and kept while he was incarcerated, and letters written to him by his young daughter during that time.

The ways in which New York’s theater community responded during this era is also explored through a selection of programs, photographs and other ephemera. On view is an original souvenir book for the 1943 production of Othello, starring Paul Robeson, an active Communist and the first Black actor cast in the role in a major US Shakespearean production, who was later investigated for his political expressions. Originally staged in 1934, The Children’s Hour was revived in 1952 at the height of the Red Scare and directed by its playwright Lillian Hellman, who had been blacklisted in Hollywood.

Blacklisted ultimately features more than 150 artifacts, including historical newspaper articles, film clips, testimony footage, telegrams, playbills, court documents, film costumes, movie posters, scripts and artwork. Each artifact is a piece of an elaborate plan to equate progressive culture with the Red enemy within.

It is a timely exhibit, indeed (and should be seen in concert with another on view across Central Park, the Jewish Museum’s Ben Shahn: On Nonconformity).

Blacklist is coordinated for The New York Historical by Anne Lessy, assistant curator of history exhibitions and academic engagement, with contributions from Emily Pazar, assistant curator of decorative arts and material culture. I asked Lessy to discuss the relevance of this important dive, given the White House’s executive order signed in March, dubbed “Restoring Truth and Sanity to American History”—which labels (and dismantles) national museum exhibits critical of the United States.

Why is the Red Scare such a New York story?

Many Blacklisted creatives were from New York City, and even more were connected to the New York theater world. Great Depression–era theater troupes like the Group Theatre were comprised of members who later found themselves entangled in the postwar Red Scare. A number of artists got their start in New York City nightclubs, such as Café Society in the Village.

I was just reading the Gertrude Berg story in the New Yorker, in which Emily Nussbaum speaks of Connections and Red Channels. Do you feel there is a sense that a new era of intimidation is on the way, and this exhibit is a cautionary tale?

The goal of the exhibition is to pose critical questions to our visitors about how and why the Blacklist took hold. How did anticommunist fervor have such an outsized influence on American politics and culture?

I grew up alongside kids whose parents were adversely impacted by HUAC. We were all Baby Boomers. Did you target the show for my generation? Or do you anticipate a broader audience?

We hope the show appeals to visitors of all ages, with the opportunity to learn and reflect on the Red Scare phenomenon. Some visitors will have personal memories and experiences. Hopefully the show creates a cross-generational dialogue about the significance of the Blacklist and what it says about American democracy.

The artifacts you exhibit run the gamut from toxic to commonplace. How intertwined with daily life was the Red Scare?

The postwar Red Scare was very intertwined in daily life. On display are newspapers and magazines, breathlessly covering the House Committee on Un-American Activities. The blacklist shaped who and what you would see at the local movie theater. It informed the political discourse and political speech.

For blacklisted creatives and their loved ones, the postwar Red Scare was even more personal. We see drawings and letters a young Mitzi Trumbo sent to her father, Dalton Trumbo, when he was imprisoned as a member of the Hollywood Ten for contempt of Congress. Other artists had their passports seized, so they lost freedom of movement. Nearly all Blacklisted creatives experienced economic insecurity and hardship, and often had to find new ways to support themselves and their families after being shut out of their chosen professions.

What is your conclusion? Or do you want the viewer to come to it through the evidence?

We hope visitors will engage, learn and reflect. We ask the question at the conclusion of the show: How can we best protect our First Amendment rights and freedoms? We look forward to hearing their answers and responses.

The post The Daily Heller: Smearing Writers and Artists With a Red Stain appeared first on PRINT Magazine.