Industry perspective by industrial design educators Juan Noguera and Tom Weis.

The Doomsday Clock symbol, originally designed in 1947 by Martyl Langsdorf for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, had a simple symbolic purpose: The closer we are to midnight, the closer we are to the destruction of the world as we know it. The Bulletin was established by Albert Einstein, J. Robert Oppenheimer and the very scientists (physicist Alexander Langsdorf, husband of Martyl, was among them) that helped to usher in the atomic age during the Manhattan Project. Since that time, the Doomsday Clock has continued to highlight the looming peril associated with increasingly hazardous technologies and events that seem to proliferate daily. The Science and Security Board of the Bulletin adjusts the Clock each year, considering climate change, disruptive technologies, and biothreats alongside nuclear dangers.

We met Rachel Bronson, president and CEO of the Bulletin (2015 to 2025), over our years consulting in the nuclear policy field, and she’s since become a friend. She reached out to us last April to ask what we thought about reworking the Doomsday Clock. The Clock was due for an update. Residing at the University of Chicago and taken out yearly for the annual setting of the Clock hands in Washington DC, the previous version had some wear and tear rendering it a bit too fragile for the yearly reveal of the Clock. (Nothing like a live event about the looming threats to humanity with the Clock toppling to the ground!). Bronson asked whether we thought there might be interest for anyone to take on a project of this nature. A redesign would need to convey the importance of the message while addressing the functional aspects necessary for the annual Clock setting.

When she reached out, we saw an opportunity to convey a story within the design of the Clock itself. From the start, our approach was shaped by a shared curiosity about how tradition and innovation intersect in design as well as the worlds of science, engineering, and countless other disciplines. The Doomsday Clock is an artifact rooted in historical significance and contemporary urgency. Our goal was to honor its legacy while embedding a message about the space between time-honored traditions and novel approaches and technologies.

A Design Process Rooted in Tradition and Innovation

Designing the new Clock required us to strike a delicate balance between honoring tradition and embracing modernity. Its redesign needed to carry forward the weight of its history while standing as a reflection of the present moment and the technological tools shaping our future.

Our approach was shaped by a shared curiosity about how tradition and innovation intersect in design as well as the worlds of science, engineering, and countless other disciplines.

Collaborative Ideation and Digital Tools

Our collaboration was largely remote, yet we worked in tandem through a shared digital workspace. Using a large virtual canvas, we layered hand sketches, Post-it notes, references, and research findings, engaging in a process that mirrored how designers have worked for decades. This stage was crucial in exploring early concepts, allowing us to iterate and refine our ideas organically, much like traditional studio-based design discussions.

Images showing hand-drawn sketches processed with generative AI model Vizcom in order to generate a variety of options in the ideation process

However, we also recognized the potential of generative AI to accelerate our exploration of form, material, and structure. To complement our traditional sketching methods, we used Vizcom, an AI-driven visualization tool, to transform our rough hand-drawn concepts into fully realized three-dimensional renderings. This process allowed us to quickly test a broad range of possibilities, particularly regarding material selection, surface treatments, and potential finishes.

The use of AI in design is often met with a mix of fascination and skepticism. As educators and practitioners, we see it not as a replacement for human creativity but as an amplifier, allowing us to explore iterations quickly, refine ideas, and push beyond conventional constraints. This project became an opportunity to demonstrate how these tools can coexist with traditional design sensibilities rather than replace them. The use of AI to achieve a positive end is also a reminder that today’s environment has become more complex than ever, with disruptive technologies offering humanity new benefits while producing emerging risks.

Images showing hand-drawn sketches processed with generative AI model Vizcom in order to generate a variety of options in the ideation process.

The results from Vizcom helped inform our early conversations about materials and fabrication. Seeing multiple AI-generated iterations at once allowed us to compare variations in color, reflectivity, and texture, ensuring that our final design would align with both the symbolic and functional goals of the Bulletin.

Fabrication: Fusing Advanced Manufacturing with Craftsmanship

The connection between old and new was not just present in our design methods; it was equally central to our fabrication process. We deliberately chose a hybrid approach, combining cutting-edge digital manufacturing with traditional craft techniques.

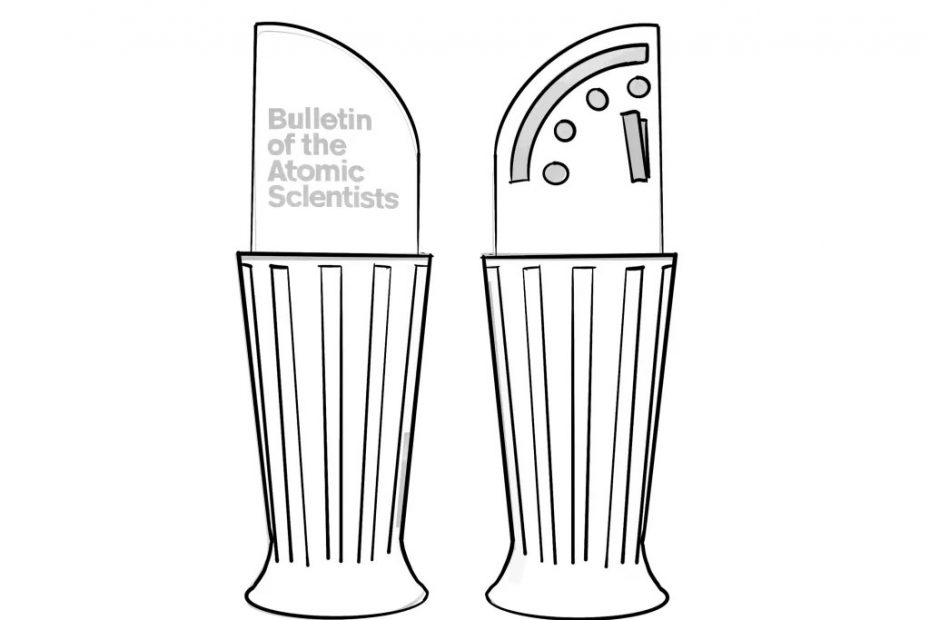

3D printed scale model of potential design candidate

The Clock face was designed using CAD software to ensure precision and longevity. To achieve the necessary scale and durability, we opted for 3D printing, producing the entire face as a single seamless piece on a BigRep 3D printer housed at RIT’s Student Hall for Exploration and Development (SHED). This large-scale industrial printer enabled us to create a sturdy, high-fidelity structure that could withstand handling and transportation, an issue that had plagued previous Clock versions.

BigRep large format 3D printer during the process of creating the single piece Clock top. The total print time was over five days.

Beyond its physical form, the Clock face integrates nearly 200 embedded magnets, allowing for a modular, reconfigurable system. These magnets provide a mechanism for easily adjusting the hands, the time, and textual components each year when the Bulletin revises the Clock’s setting. This flexibility ensures that the redesigned Clock remains adaptable for future updates without requiring extensive rework.

In contrast, the pedestal supporting the Clock was entirely handcrafted, embodying a different philosophy rooted in human touch and material sensitivity. Using classic woodworking techniques, we shaped the spindles through woodturning and formed the sidewalls of the pedestal by laminating panels of veneer and plywood. The warmth and organic quality of the pedestal serve as a counterpoint to the precision of the 3D-printed Clock face, intentionally contrasting handwork with the novelty of digital fabrication.

In the woodshop, spindles were hand-turned to form the structure of the pedestal.

The AI-assisted design process allowed us to explore new possibilities in a way that previous designers of the Clock never could, while the traditional woodworking of the pedestal relied on a pace that is determined by hand and material.

Symbolism in Execution: Learning from the Past to Confront the Future

In many ways, the methods we employed in designing and building the Doomsday Clock serve as an analogy for the Bulletin’s broader message. We looked to the past for inspiration in our approach, integrating foundational design practices and craftsmanship.

Partially completed Clock and pedestal shown (left), including the bearing mechanism used to rotate the Clock face at the time of the reveal (center). (Right) Noguera with a fabricated Clock piece.

The tension between history and the unknown was central to every decision we made on this project. The AI-assisted design process allowed us to explore new possibilities in a way that previous designers of the Clock never could, while the traditional woodworking of the pedestal relied on a pace that is determined by hand and material. By bringing these approaches together, we ensured that the new Doomsday Clock was not just a redesign but a statement: progress and preservation must coexist.

89 Seconds to Midnight

The redesign of the Doomsday Clock wasn’t just about revamping an object; it was about reinforcing a message that remains as pertinent today as it was when the Clock was first conceived in 1947. As we collectively navigate the human-made threats to the world, it is neither a retreat to the past ways of doing things nor the promise of shiny new tools and software that will guide us to a safer path. Rather, it is knowing how and when to draw from both of these directions with thoughtfulness and care.

A number of magnetic modules composing the text and hands of the Doomsday Clock are shown on a workbench top.

As the Clock continues to be regularly adjusted, we hope this redesign serves not only as a visual reminder of the looming dangers but also as an inspiration for action. The future is not predetermined, it is shaped by the choices we make today.

Following the press event for the recent reveal of the Clock time, we had the occasion to meet Suzanne Langsdorf, daughter of Martyl and Alexander. She greeted both of us with a friendly handshake using both of her hands, as if she had known us for years. Her warmth was a welcome embrace among a DC crowd that can feel intimidating to an outsider. We had the opportunity to talk with her about growing up with a father who contributed to the Manhattan Project and a mother who conceived of the Clock that we had just contributed to. She spoke of their positive outlook, as well as their attitude that “one just needs to get on with the work” no matter what the situation might be. A fitting reminder that the Doomsday Clock doesn’t indicate the passage of time; it urges us to take responsibility for the time we have left.

In January, it was set at 89 seconds to midnight. There is indeed work to be done.

The authors: Tom Weis (left) and Juan Nogera (right)

Tom Weis is the founder of Altimeter Design Group and associate department head, Industrial Design, at the Rhode Island School of Design.

Juan Noguera is an assistant professor, Industrial Design, at the Rochester Institute of Technology.

The post A Symbol Reimagined: Merging Tradition and Technology in the Doomsday Clock appeared first on PRINT Magazine.