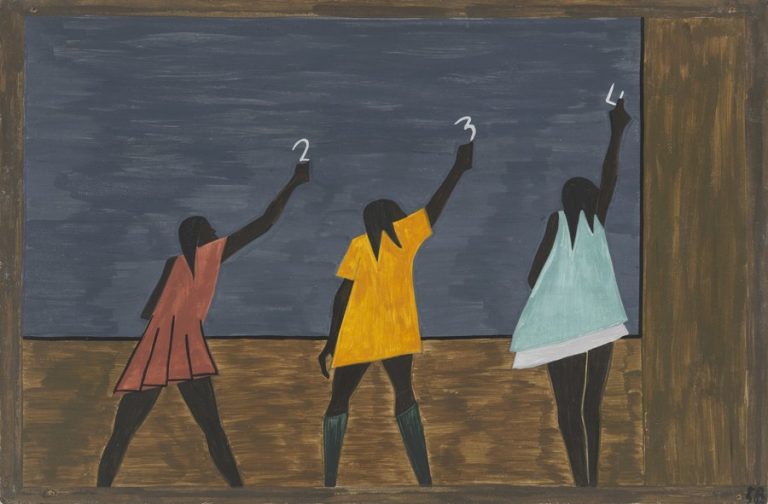

The whitewashing of history in our dominant culture comes as no surprise. Systemic deficiencies in our country’s treatment and calculated erasure of the BIPOC community underpin America’s very existence, as the Black Lives Matter Movement and countless others brought to the fore in a groundswell of outrage spurred by George Floyd’s murder in 2020. As a mirror of our culture at large, the design world has followed suit, too often omitting Black voices and pushing designers and artists of color to the margins.

Artist, designer, writer, and curator Silas Munro was confronted by this reality while in college. “I’ve taken two pretty amazing design history learnings,” he told me. “Both were really amazing and thoughtful, but seeing Black folks like me, seeing queer folks in design history, were the outliers.”

Munro wasn’t the only one identifying these glaring gaps in their design schooling, as he found a kindred spirit in CalArts classmate Tasheka Arceneaux-Sutton, and then again within a student he advised at the Vermont College of Fine Arts a few years later, Pierre Dowens. The three teamed up as they researched BIPOC designers, amassing their findings with the goal of publishing a book. In time though, the trio came to realize that their work required a format beyond the confines of a book, and they began to conceptualize an online course to disseminate to the masses.

On January 1, 2021, their “Black Design in America” course was released, and BIPOC Design History was born, facilitated by Munro’s graphic design studio Polymode. “We were not prepared for the reaction,” said Munro. “There was an outpouring of support and interest in the classes.” With the success of this first class fueling their fire, Munro and the rest of the BIPOC Design History team have continued to produce and curate online design history courses that fill the egregious voids left in most design curricula. Since the inaugural Black Design in America course, BIPOC Design History has also released “Incomplete Latinx Stories of Diseño Gráfico Borderlands/ La Frontera*,” which covers the work and histories of art and design in Latin America. Now, they are unveiling their latest offering in the series, “Design Histories in Southwest Asia & North Africa: Voices from the SWANA Diaspora,” which will begin this Saturday, May 13th, with its first recording that students can tune into live for a real community-based learning experience.

While each of the BIPOC Design History courses can be accessed at any time, participating in the classes live enhances the learning experience exponentially, allowing for real-time interaction with fellow students, the speakers, and the facilitators. “The recorded classes are great, licensing the classes is great, but there’s something special about it being live,” explained Polymode Studio Manager, Audrey Davies. “There’s a strong sense of community in the live classes, where people can talk to the person who just gave a lecture and ask a question directly, or talk to Silas, or talk to each other. It’s just like a real class that’s a very mixed group of people that would not necessarily be together otherwise.”

Polymode Senior Designer and curator of the new SWANA course Randa Hadi shared a similar sentiment in regards to the live Black Design in America classes. “The most inspiring thing about the talks was the Zoom chat,” she said. “People were really vulnerable, and Silas did a really good job of asking tough questions and creating a safe space. So people were dropping in so many links, videos, podcasts, and articles, I think it speaks to this collective knowledge and collective sharing.”

The BIPOC Design History courses attract all manner of participants ranging in ages 18 to 80, from active students to major current players and tenured professors, like Tré Seals of Vocal Type and Cheryl D. Miller, who penned the seminal 1987 PRINT article “Black Designers: Missing in Action.” This multigenerational, multi-experience, multi-geographical participant body creates a rich learning environment that’s rife with a diversity of perspectives, points of view, and lived experiences that only enhances the material being learned.

“It was multiple levels of learning, it went both ways,” elaborated Munro on the magic of those Black Design in America course live classes. “The younger design students and their questions and their perspective were really refreshing as they interacted with these expert-level design historians and professional designers. It made this really healthy dialogue where we were all exploring and testing the limits of how we welcome Black, people of color, and Indigenous histories into design history, and what it means to shift the discourse.”

Central to supporting this diversity of participants is making sure BIPOC Design History courses are easily accessible to all. Too often, resources, tools, and educational materials are prohibitively expensive, especially to those who need them the most. The Polymode team has prioritized keeping BIPOC Design History affordable to all. “Marginalized voices are always pushed to the margins, thus the whole title, but also they don’t have the money. They don’t have the accolades. They don’t have the ability to to be in these spaces,” said Polymode co-founder and partner, Brian Johnson. “So we wanted to make sure, from a capitalistic cost perspective, that a student could afford to be there when this is the most important thing for that student.”

This latest BIPOC Design History course, SWANA, has specifically been developed to highlight, uplift, and amplify the voices of women in that region who are often unheard. As a native to Kuwaitt, Hadi has deeply personal ties to the subject matter she curated and will facilitate in the classes. “I grew up in a household where it was very much about sharing oral stories around the dinner table and around the living room,” she said. “I wanted to take that experience of sharing narratives and histories about the SWANA region and give people access to that. I’ve been in the U.S. for 12 years now, and I haven’t had access to this kind of information. For me, it was about creating a course that people who are living in this one region can learn from, but also the diaspora, because that’s another reality for people who are from that area.”

Considering SWANA’s feminist subject matter, it stands to reason that 80% of the speakers in the course are women. “That was also really important to me,” Hadi said with pride. “I grew up with strong female figures in my family, and I wanted to make sure that their voices are being highlighted. Within this one region, their voices are often oppressed. The overarching narrative is wanting people to feel like they’re seen in design history.”

SWANA is far from the end of the road for BIPOC Design History. The team is already in the process of developing their next course, with Johnson leading on the project. Beyond additional courses, they’re intent on inspiring others to teach these topics so that diverse design education becomes standard. “Our dream is that all educational systems already teach this,” said Johnson. “Maybe that’s too far out there, but this shit should be taught in elementary, middle school, and high school, and in higher education university systems already. They’re really behind. If we’re the bridge or the facilitator to get there by saying ‘You’re not alone, we’re out in the wilderness, we have a lantern, here is the light, come towards us,’ that’ the dream.”