Responsibilization in Practice

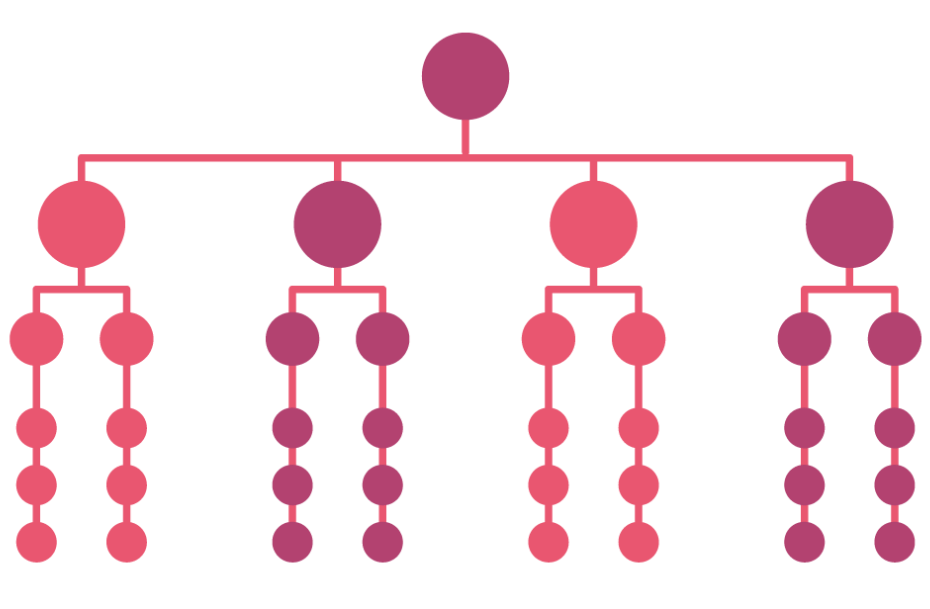

I was socialized in a business structure modeled from the military structure my grandfather (also named Sam) operated in as an army private during WWII — one which can probably be traced back to the Roman Empire or even before. A top-down, centralized leadership approach characterizes the classic hierarchical structure. Authority and decision-making power flow from the top level (general, or in business: executive leadership) down to the lower levels (colonels, lieutenants, sergeants, privates, etc, or in business: managers, employees, etc.). This structure has clear lines of authority, with directives and decisions originating from senior management and cascading downward.

Military organizations traditionally employ strict hierarchical structures to maintain order and discipline in high-stakes, complex environments — and in these structures, orders from superiors must be followed without question. There are benefits to this approach on the battlefield. Top-level leaders make critical decisions because they (in theory) have a broad view of the strategy and goals. There’s a clear chain of command to control operations and ensure directives are followed consistently and to the letter. With that chain of command comes clear lines of authority and accountability, making it easier to assess responsibility in the event of successes or failures. And a hierarchical structure can manage very large groups of people — like an army — making it easier to organize, train, and deploy troops and resources at a massive scale.

But what happens when a soldier gets cut off from central command and realities on the ground shift? Those lower in the hierarchy usually have limited decision-making authority, which can stifle creativity when it’s needed most. Even if they do have access to central command, there are communication challenges — information may get filtered or delayed as it moves up and down the hierarchy, making quick decision-making difficult and leading to a lack of agility in the face of changing conditions and emerging opportunities.

Netflix’s Autonomous Content Teams

Business isn’t war, so let’s discuss something more fun: TV shows. Most traditional networks or studios structure their organizations in a hierarchical manner similar to the military, with top-down instructions, approvals, and accountability. Let’s bring a new show to life in the traditional network/studio model. In this scenario, we’re an in-house development team with an idea: a sitcom about six twenty-somethings living in New York City, following the hilarious misadventures of this tight-knit group as they navigate work, life, and love.

We need to pitch our concept — the premise and target audience of our show — to managers and executives up the hierarchical structure. We do pitch after pitch, incorporating feedback (hopefully refining, not watering down the idea) until we get to the decider at the top, the network executive. They also want changes, but they give it the green light, great! We develop and produce a pilot episode and screen it, again to the network executive or a team of senior executives for approval to invest and move to a full series.

This approach may have worked in the 90s when there were a handful of networks and channels developing content for a mass audience on cable television. Still, it’s not agile enough to handle the niche content tastes and changing demographics of today’s market. Netflix created a different approach that turned it into the hit machine it is today, innovating not just on how content is delivered to audiences through streaming but also on how original shows are developed and brought to the platform.

Unlike traditional studios, content decisions at Netflix are typically made by small, cross-functional teams, which have the autonomy to decide which shows and projects to pursue based on their assessment of market potential and audience preferences. These content teams rely on extensive data and analytics to inform their decisions — and have access to vast amounts of information about viewer preferences, watching habits, and content performance. This data empowers them to make informed choices about the content they believe will resonate with audiences. The autonomy of these content teams comes with a high level of responsibility. They are accountable for the success of the content they choose to produce. If a show doesn’t perform as expected, the team takes responsibility for the outcome. They also embrace an adaptive approach to content creation. If a team sees that a show isn’t gaining traction or meeting audience expectations, they have the authority to make changes, pivot, or even discontinue the project. The responsibility and authority are in the hands of the teams closest to the creative and strategic process.

An early example of Netflix’s approach to content creation through small, autonomous content teams is House of Cards. A content team at the streamer analyzed the viewing habits and preferences of its subscribers and identified a strong interest in political dramas, as well as a preference for the work of the show’s director, David Fincher. This data-backed approach, combined with the autonomy of the content team, led to the green-lighting of House of Cards.

Stranger Things is another prime example. The show was created by the Duffer Brothers, who pitched it to various networks. Netflix’s content team, having analyzed data showing strong viewer interest in ’80s nostalgia and supernatural themes, gave the green light to the show. It became a massive hit, showcasing the effectiveness of data-driven, autonomous content teams.

Responsibilization at Michelin

The idea of decentralizing decision-making and putting responsibility in the hands of those closest to the work is called Responsibilization, a term coined by the French tire company Michelin. The French word responsibilisation loosely translates to empowerment. Authors Gary Hamel and Michele Zanini chronicle Michelin’s move towards responsibilization in their 2020 book, Humanocracy: Creating Organizations as Amazing as the People Inside Them.

Hamel & Zanini, Humanocracy

In the mid-2000s, Michelin launched a company-wide program to improve proactivity through standardized processes, tools, dashboards, and performance audits — they called it the Michelin Manufacturing Way (MMW). And it failed. It turns out that trying to transform people into machines isn’t the best approach to creativity and continuous improvement. As MMW rolled out, leaders in the company raised concerns that the standardized approach was making it harder for local initiative and creativity to thrive. It also went against a key company value of their cofounder Édouard Michelin, who once said, “One of our principles is to give responsibility to the person who carries out a given task, because he knows a lot about it.”

Standardization efforts at Michelin yielded diminishing returns, while market dynamics demanded creativity and flexibility. In early 2012, a workshop hosted by Jean-Michel Guillon — then head of the personnel department — revealed a unanimous consensus: frontline teams needed more autonomy to drive local operations. Bertrand Ballarin, the manager of Michelin’s Shanghai plant, emerged in the workshop as a vocal advocate. With a track record of turning around underperforming factories, Ballarin believed in shared purpose, skill development, and granting production teams more freedom.

His journey toward enacting responsibilization at Michelin began with recruiting volunteer supervisors and teams willing to pioneer this new approach. Leadership asked teams two pivotal questions: “What decisions could you make without my help?” and “What problems could you solve without support staff involvement?” As Hamel and Zanini explain, workers were encouraged to initially focus on expanding their autonomy in just one or two key areas. Teams were given 11 areas to choose from and asked to document their progress through notes and videos. By March 2013, experiments gained momentum, driven by teams’ realization that they didn’t need approval and no one would stop them (what a concept!). The crew at the factory in Le Puy took on responsibilities like shift scheduling, while the team in Homberg improved internal coordination, reducing downtime substantially.

The subsequent steps saw responsibilities growing, roles evolving, and the redefinition of boundaries. Frontline employees played significant roles in safety, quality, and scheduling, with access to necessary information. They invested in enhancing skills, and managers transitioned from bosses to mentors. The initiatives brought remarkable improvements. For example, the Homburg team witnessed a 10% increase in productivity and a reduction in defects from 7% to 1.5%, with absenteeism dropping from 5% to virtually zero.

The responsibilization transformation extended beyond manufacturing, influencing the organization’s structure. In 2018, a major reorganization, developed with minimal executive input, further decentralized decision-making. The CEO declared empowerment as a new company hallmark. Michelin’s journey vividly illustrates the power of trust and empowerment. It showcases how employees, when given autonomy and support, can bring about profound changes in their roles and contribute significantly to a company’s success. Unlike typical top-down initiatives, it was built on persuasion, persistence, and a deep belief in the potential of every individual within the organization, turning ordinary jobs into avenues for personal growth and transformation.

Responsibilization at Buurtzorg

Hamel and Zanini give two more great examples of responsibilization in Humanocracy. Buurtzorg is a Dutch home healthcare organization — cofounded by Jos de Blok, who envisioned more patient-centered healthcare. De Blok, a community nurse himself, recognized the inefficiencies and frustrations within the traditional, hierarchical healthcare model. He believed in putting patients at the heart of care, and he knew that to achieve this, he needed to empower the nurses providing the care.

Buurtzorg means “neighborhood care” in Dutch. The core of their approach is simple yet revolutionary: empower self-organizing teams of nurses to take full responsibility for their patients. These teams operate independently, making decisions about patient care, scheduling, and administrative tasks collectively. The impact of this approach on Buurtzorg’s business and patient outcomes has been nothing short of remarkable. By redistributing responsibility and decision-making to the frontline nurses, Buurtzorg reduced bureaucracy and overhead costs. With a flat organizational structure and lean management, the company eliminated unnecessary administrative layers.

This lean, responsive structure not only reduced operational costs but also allowed nurses to spend more time with patients, delivering higher-quality care. The result was increased patient satisfaction and better health outcomes. The nurses could tailor their care to the specific needs of their patients, building more personal and empathetic relationships. By giving nurses autonomy, trust, and the freedom to make decisions, Buurtzorg harnessed the collective wisdom of its teams. The impact on patient outcomes was tangible, with reduced hospitalization rates and improved quality of life for those under Buurtzorg’s care.

Responsibilization at Haier

The Haier Group, a global home appliance manufacturer based in China, enacted responsibilization through its innovative use of micro-enterprises. The journey began in the early 2000s when Zhang Ruimin, Haier’s visionary CEO, realized that the company needed a radical transformation to stay competitive. Faced with global market challenges and a need for agility, Zhang introduced the concept of micro-enterprises within the company.

Micro-enterprises are small, self-managing units operating like independent startups within the larger Haier framework. These micro-enterprises are typically responsible for a specific product, market segment, or service. Instead of following traditional top-down management, Haier assigned decision-making power to these units, allowing them to operate autonomously and responsibilize their teams. One compelling example of Haier’s transformation was its approach to innovation. In a conventional hierarchical structure, innovation often gets bogged down by bureaucratic processes and siloed thinking. Haier changed the game by fostering a culture of entrepreneurship and autonomy within each micro-enterprise. For instance, Haier’s appliance design micro-enterprise was given the freedom to create and launch new products rapidly. These small teams were accountable for everything, from product concept to development and marketing. This autonomy allowed them to respond swiftly to market demands and customer feedback.

The impact on business outcomes was profound. Haier’s responsiveness and speed-to-market improved significantly. The company could introduce innovative products ahead of competitors, capturing market share and customer loyalty. Furthermore, by distributing decision-making to the teams closest to the work, Haier reduced the burden of middle management and eliminated layers of bureaucracy, streamlining the organization and making it more agile and cost-effective. Additionally, Haier introduced a “platform” approach to connect and coordinate these micro-enterprises. While individual teams had autonomy, they could collaborate and share resources through Haier’s platform. This interconnected ecosystem allowed them to leverage each other’s strengths and accelerate their growth.

Haier’s shift toward responsibilization and micro-enterprises revolutionized its business model. By 2018, the company’s revenue exceeded $40 billion, with operations in over 100 countries.

How Does Accountability Work?

You might be wondering, this is great, but how does accountability work in organizations that adopt responsibilization? Accountability is so neat and clear in a top-down hierarchy — it flows with the chain of command. But in responsibilized organizations, there is no chain of command. Responsibilization redistributes authority and responsibility to small teams, empowering them to make crucial decisions in their respective areas. While this may seem like it could lead to a lack of accountability, it’s quite the opposite.

Accountability in responsibilization is built on a foundation of transparency, shared responsibility, and continuous feedback. Small teams are entrusted with making decisions, but they are also accountable for the results. They define their own goals and objectives, which means they take ownership of their performance. This decentralized model also encourages a culture of peer accountability. Team members hold each other responsible for their actions and decisions, fostering a sense of collective ownership. The shared mission and objectives of these teams help maintain accountability, as everyone aligns towards common goals.

Regular communication and feedback loops are crucial in responsibilization. Teams continuously evaluate their performance and make adjustments as needed. This self-assessment and adaptability ensure that accountability remains at the forefront of the approach. It’s not about avoiding responsibility; it’s about taking responsibility at every level of the organization. And finally, accountability in responsibilization benefits from data and metrics. Teams monitor their progress using clear, objective indicators. This data-driven approach allows for a more accurate assessment of performance, helping to identify areas that require improvement.

How To

Implementing responsibilization in a company is a significant transformative process that involves shifting decision-making and accountability to the individuals and teams closest to the work. Here’s a very high-level approach to getting started:

Leadership Commitment: Start with strong commitment from top leadership. Ensure leaders understand and support the shift to responsibilization. Leadership should be willing to embrace change and lead by example.

Education and Training: Educate the entire organization about the concept of responsibilization. Conduct training sessions to help employees understand the new model, their roles, and the benefits.

Pilot Selection: Choose specific areas or functions to pilot responsibilization. These should be manageable, well-defined areas that can serve as testing grounds for the new approach.

Team Formation: Create self-managed teams for the selected areas. These teams should consist of individuals with the necessary skills and expertise to operate autonomously.

Objective Setting: Define clear and measurable objectives for these teams. Ensure that everyone understands what success looks like for their respective areas. Objectives should align with the company’s overall goals.

Empowerment: Grant the self-managed teams the autonomy to make decisions related to their work, including decision-making authority, resource allocation, and goal setting. Encourage them to take ownership of their responsibilities.

Resource Support: Provide the necessary resources, tools, and support to help these teams achieve their objectives, which might include additional training, access to data, and any required technology or equipment.

Feedback and Iteration: Establish a system for continuous feedback and performance evaluation. Teams should regularly assess their progress, identify areas for improvement, and make necessary adjustments. Use data-driven metrics and Key Performance Indicators to measure their performance.

Responsibilization is an ongoing process of adaptation and learning. As the pilot areas demonstrate success, consider expanding the concept to other parts of the organization. Encourage a culture of open communication, transparency, and shared responsibility to ensure its successful implementation.

Sam Aquillano is an entrepreneur, design leader, writer, and founder of Design Museum Everywhere. This post was originally published in Sam’s twice-monthly newsletter for the creative-business-curious, Business Design School. Check out Sam’s book, Adventures in Disruption: How to Start, Survive, and Succeed as a Creative Entrepreneur.

This issue of Business Design School was made possible by Aardvark. Aardvark is a financial strategy studio for the creative industry. Also known as “the fractional finance department for creative agencies,” they provide all-in-one CFO, bookkeeping, tax, cash management, payroll, invoicing, and other financial tasks needed to run a business.

Header image: Vector Mine