Good design is good business.

Thomas Watson Jr., Former President, IBM

I started my design career as an industrial designer at Bose, designing consumer electronics. Since design was foreign to those around me, I was endlessly asked, “What’s an industrial designer?” — and sometimes even, “Do you design factories?” As funny as that was to hear over and over (and over), it did make me wonder, and actually concerned me, that the people around me didn’t know that there was an entire professional field focused on creating the products they see and use daily.

My friend and renowned industrial designer Michael DiTullo often gets the same “What is an industrial designer?” question. He usually responds with a helpful analogy: architects create buildings, industrial designers create products — industrial designers do for products what architects do for buildings. I love that analogy, especially since many of the first industrial designers were architects.

Now, working as a business designer, I regularly get the questions, “What’s a business designer?” or “What exactly is business design?” It’s a fair question since business design is a relatively new sub-field of design. And that question is why I started Business Design School — so we can learn the art of business design together.

So, what is a business designer? I’ll channel Michael for a second: a business designer does for businesses what an architect does for buildings. That’s all to say: a business designer designs businesses (elements of a business).

Business design is a field that applies design methodologies and principles to business challenges and strategy. It bridges and synchronizes between the goals of the business and the impact of design to deliver long-lasting, scalable value to an organization and meaningful connections to users and customers. Think of it like a hybrid practice that blends business acumen with creative problem-solving. The core goal of business design is to innovate and improve business models, processes, services, and strategies by focusing on human-centered design, user experience, and a deep understanding of customer needs.

If you can design a building, you can design a business. Let’s break down these words: business + design.

What is Design?

I recently saw Rai Inamoto, Founding Partner of I&CO, a business invention firm, describe design as a suitcase word. Inamoto shared that the term suitcase word was coined by the late Marvin Minsky, the co-founder of MIT’s AI lab — a suitcase word is a word which “means nothing by itself, but holds a bunch of things inside that you have to unpack.”

I unpack design as three things: a unique way of thinking, making, and deciding.

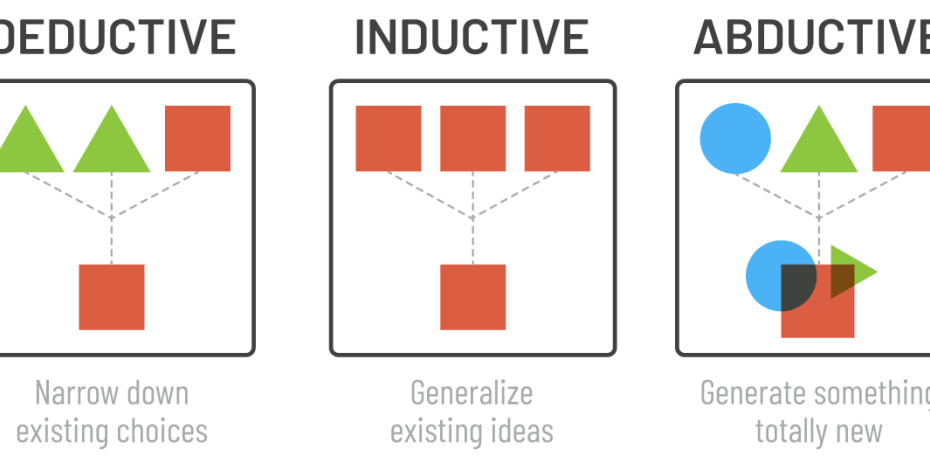

Thinking: Design as a way of thinking means reasoning through a space of ambiguity, uncertainty, and complexity — to do this, designers use abductive reasoning rather than deductive or inductive.

Deductive reasoning is a logical process in which a conclusion is based on the alignment of multiple premises generally assumed to be true. It’s logical as long as the premises are known and true. For example, if all birds can fly (premise), and a sparrow is a bird (premise), then a sparrow can fly (conclusion).

Inductive reasoning is the opposite of deductive. It involves broad generalizations from observations of existing truths and then making general conclusions or theories. For example, every swan we have seen is white; therefore, all swans are white.

Abductive reasoning begins with an incomplete collection of observations and proceeds to a likely, possible explanation. It involves looking at the evidence and considering what could cause a given phenomenon — and it typically yields a hypothesis, which is tested. A good example is a doctor diagnosing a condition based on limited information. If a patient has a high fever and a sore throat (observations), one possible explanation (hypothesis) is that the patient has strep throat.

By thinking this way, designers effectively manage and make change where information is unclear, incomplete, and conflicting — where there is no obvious or near-obvious answer. It allows for a broad exploration of possibilities. As an industrial designer at Bose in the early 2000s, I was on a team tasked with designing a portable speaker for the iPod. Talk about an open-ended problem with no logical solution! We had some hard data points, including our existing (non-portable) SoundDock product and a plethora of competitive products already on the market, but what would a portable product from Bose look and function like? We used abductive reasoning to listen to our customers about their needs and desires and explore a ton of possibilities to diagnose the opportunity and get to our best answer.

Making: Design as a way of making means turning ideas into tangible (or digital) artifacts. Like abductive reasoning, making sets designers apart in that designers make to learn. Gary Hamel and Michele Zanini said it well in their book Humanocracy, “The ethos is show, don’t tell. Build a styrofoam model, sketch something on a napkin, lay out a storyboard, shoot a video. The simple act of translating a concept into a thing often reveals hidden flaws and opportunities to make the idea better. Everyone needs to be a maker, to roll up their sleeves, get their hands dirty, and build something. While the sheer profligacy of experimentation — ‘Look at all this wasted effort!’ — may irk the bureaucratic mind, it’s the only way to get to the future first.”

Making things — or prototyping — is design as a craftinvolving technical skill, the ability to discern the level of detail or fidelity a given concept prototype requires to learn from it, and the courage to try and fail. Making prototypes allows us to see and hold the future without investing the time and treasure to get there. Designers test and refine their concepts to get to the best version of the idea. As Eric Beyer, Executive Director of Prototyping at 3D Color, once shared, “Prototyping is the ‘rough draft.’ The more rough drafts one does, the better the final outcome, usually.”

We made hundreds of prototypes to design the SoundDock Portable — ranging from a works-like prototype that was batteries, speakers, and wires seemingly strewn together on a cart (but it worked!) to looks-like models to explore size, form, and feel to looks-like/works-like prototypes you’d swear were the real thing (but they weren’t!). We made things, learned from them, made some more, refined them, and made again — we made to learn, and in doing so, we de-risked the ultimate decision to invest in the product development and business system required to bring a product to market and sell it to thousands of people.

Deciding: Design as a way of deciding is the culmination of design thinking and making — it’s why we design to make the most objective decision based on numerous subjective bits of evidence. It means making decisions based on research, data, and testing — choosing between options and alternatives. If you do the thinking and making right, you reduce the risk of investments in time and money your decisions generate — because we’re not just talking about immediate choices, we’re talking about long-term strategic choices that impact the future.

For the SoundDock Portable, we had to decide on functional features: how should it sound, how heavy should it be, and how long should it last so that it will meet the needs of our customers? We had to decide on aesthetics: what should it look like, how should it feel so that it will meet the desires of our customers? And we had to decide on the business aspects: how much will it cost us to make, how much can we sell it for, how do we position it in the market? We could confidently make these decisions because of all the design thinking and design making that came before.

What is Business?

Business is an organized system of sustained value exchange between a company, consisting of people, assets, and activities, and customers with needs and desires. Businesses transform talent, labor, and materials to create value, whether in the form of products, services, or solutions, and exchange this value with customers or clients — whose needs or desires are met by those products, services, or solutions — for other forms of value, typically money. Every business element in this framework can be thought about, prototyped, and decided on — it can all be designed. Let’s use a Business Design Framework, see above.

Customers— People with Needs & Desires

While you may not be able to design your customers, they are humans, after all — you can seek to understand your customers and frame opportunities based on their demand. Talking to customers is critical to business success. Call it user research, market research, whatever, but I agree with Aaron Levie, CEO of Box, when he says, “You’ll learn more in a day talking to customers than a week of brainstorming, a month of watching competitors, or a year of market research.”

Take the Ford Maverick, for example — it’s a compact pickup truck Ford introduced in 2021. The Maverick’s development was a direct response to a growing market segment of customers that desired the versatility of a truck but in a more compact, fuel-efficient, and affordable package than larger model trucks like the Ford F-150. Ford recognized a niche for a smaller pickup that would appeal to urban dwellers and those needing a vehicle for everyday use and occasional hauling or adventure purposes. The Maverick was designed to meet these diverse needs. Ford now dominates the small-truck market.

Company — People + Activities + Assets

A company is a group of people, activities, and assets, and there’s an entire field dedicated to designing them, called Organization Design. Organization design refers to the process of shaping an organization’s structure and roles to align with its business strategy, goals, and objectives. It involves creating a framework of activities that enables the organization to operate effectively and efficiently. Effective organization design considers various aspects, such as the distribution of resources, allocation of responsibilities, coordination of activities, and management of workflows.

You can design the configuration of your organizational structure, such as hierarchical, flat, matrix, or networked. Ford Motor Company has a traditional vertical hierarchy with a clear chain of command from top-level management to entry-level employees. The company is organized into various functional departments like finance, marketing, human resources, research and development, and manufacturing. Each department has its specific roles and responsibilities aligned with the company’s overall strategy. But Ford also exhibits characteristics of a matrix organizational structure, especially in its approach to product development, where creating a new product like the Maverick results from massive collaboration across different functional departments.

Organizing this way was a choice for Ford. Still, you can design different structures, like the collection of micro-enterprises that make up the global home appliance manufacturer Haier, which I wrote about in Issue 007. Or you can design a holacracy, like video game-maker Valve, which seemingly has no organization structure, where employees have significant autonomy — there are no managers — over what they spend their time on, how they collaborate, and what products or services they launch.

A company also consists of activities and assets which can also be designed. For example, Ford’s internal activities include research and development and financial management — you can design how you do R&D and, yes, you can design how you do financial management (see Issue 008), in that you can think, make, and decide how these activities are run (keeping in mind there are generally accepted accounting principles and as a public company Ford is held to certain standards of financial reporting). Ford’s external activities include marketing and advertising to promote products and their brand image and selling and distributing vehicles through a network of dealerships globally.

Assets are resources with economic value that a business owns and controls with the expectation that they will provide future benefits. Assets are definitely designed. Ford’s tangible assets include their manufacturing plants, the factories where they build the Maverick, and all the machines and equipment they use to make vehicles. The yet-to-be-sold inventory of vehicles is also an asset. There’s also corporate real estate, like office buildings and research centers, that they own and operate in — all physical assets designed to achieve business goals. There are also intangible assets like the Ford brand and reputation in the market, customer relationships and loyalty, and their intellectual property like patents and proprietary technology. Everything is designed.

Designing a Value Proposition

Your company, activities, and assets generate your market offering or value proposition. A value proposition is a statement that clearly identifies the benefits a product or service will provide to a specific target audience, explaining why it is superior to other alternatives in the market. It’s essentially the promise of value to be delivered and a primary reason a consumer should buy from you. And it’s useful in aligning the various elements of your business around a common strategy. In crafting a value proposition, businesses highlight the unique value they offer customers. Because you can design your company, activities, and assets, you can shape your value proposition. Here’s a high-level approach:

Identify your key customer — know who they are and understand their needs, preferences, pain points, and behaviors.

Outline benefits and features — note the key features of your product or service and translate each into benefits for the customer, showing how it makes their lives better, easier, or more enjoyable.

Differentiate from competitors — understand your competitor’s value propositions and articulate what makes yours unique by highlighting unique selling points (USPs) — things like quality, price, innovation, customer service, etc.

Craft a clear, concise statement — combine your understanding of your audience, the problem you solve, and your USPs into an easy-to-understand, compelling statement; for example, The Ford Maverick offers an efficient, versatile, and affordable urban truck experience, combining the utility of a pickup with the comfort and fuel economy of a compact car.

Test and validate — share your value proposition with potential customers to get feedback and refine as needed.

Implement across your business — ensure that all aspects of your business (people, activities, and assets) are aligned with delivering the promised value, and communicate it clearly through marketing and customer relationships.

Value Exchange

All this business design leads to the value exchange — where your business trades a valuable product, service, or solution with a customer for money. Since you can design what goes into a value exchange, you can design how you exchange value with your customers. How you accept funds is one of the most critical aspects of the buying experience — and it can be a significant differentiator. Look at Amazon’s “1-Click” or “Buy Now” button, which allows customers to make an online purchase with a single click that bypasses the traditional online shopping cart + checkout process, streamlining the purchasing experience. Amazon had a patent on this (since expired and now adopted by many other online retailers), US Patent No. 5,960,411, titled “Method and system for placing a purchase order via a communications network.”

Historically, Ford, like most automakers, relies on a network of franchised dealerships to sell its vehicles. The value exchange is multi-tiered. First, Ford manufactures vehicles and sells them to the dealerships — providing them with marketing, training, and after-sales services — then the dealer sells them to the customer, handling customer interactions, test drives, financing, and post-purchase services like maintenance.

In the late 1990s, Ford experimented with redesigning the value exchange with their Ford Collections initiative — the idea was to create company-owned dealerships that consolidated various Ford brands under one roof and allowed them to control and streamline the customer experience more directly. The company designed and launched pilot “Collections” in a few markets to test the idea, including Tulsa, Oklahoma, Salt Lake City, Utah, and Rochester, NY.

This business design did not perform as well as expected — Ford Collections struggled to achieve the projected efficiencies and improvements to the customer experience. But more dramatically, the move faced serious resistance from Ford dealers concerned about the competition from company-owned dealerships. There are also laws in the US that generally restrict automotive manufacturers from owning and operating dealerships due to franchise laws and regulations designed to protect independent dealers. Between lack of performance and legal challenges, Ford reversed course three years into the experiment and divested from their company-owned dealerships. Not every business design is a winner. Although the Collections initiative was unsuccessful, it gave Ford valuable insights into retail operations and the importance of dealer relationships. It also highlighted the complexities of changing entrenched distribution systems in the automotive industry.

Business Model

This framework represents your business model, consisting of customer needs, company structure, activities, and assets, meeting in the middle with the all-important value exchange. A business model is a conceptual framework that describes how a company creates, delivers, and captures value. It’s essentially a blueprint for how a business operates and makes money, encompassing its products or services, customer base, and financial and operational strategies. Because a business model is a series of choices, you can design it.

Ford Motor Company’s business model primarily revolves around designing, manufacturing, and selling a wide range of vehicles, including cars, trucks, and SUVs, along with automotive parts and accessories, complemented by a network of franchised dealerships for sales and service. Contrast that business model with that of Carvana. Carvana is an online-only used car retail platform allowing customers to buy, sell, and finance used vehicles online. This model eliminates the need for traditional physical dealerships, offering features like a 360-degree view of vehicles, home delivery, and a seven-day return policy, prioritizing convenience, transparency, and customer experience in the used car market — different choices, different designs.

Design is a series of informed choices stacked on top of each other until you get to the outcome. (Hopefully, the outcome you designed for — in the case of the Ford Maverick, it was; for Ford Collections, it wasn’t — but we try, test, and learn). In that way, anything can be designed because everything is a series of choices — including a business. And that’s what business designers do — combine business management with design thinking, making, and deciding to achieve a powerful mixture of economic and human outcomes.

Sam Aquillano is an entrepreneur, design leader, writer, and founder of Design Museum Everywhere. This post was originally published in Sam’s twice-monthly newsletter for the creative-business-curious, Business Design School. Check out Sam’s book, Adventures in Disruption: How to Start, Survive, and Succeed as a Creative Entrepreneur.

Images courtesy the author.