Picture a T-shirt. The image of a plain white tee, probably Hanes, likely comes to mind: crisp, classic, unassuming. And while there is, of course, a certain beauty to the simplicity and timelessness of a traditional white T-shirt, it’s still a bit basic. A little unfinished. It’s almost a blank canvas.

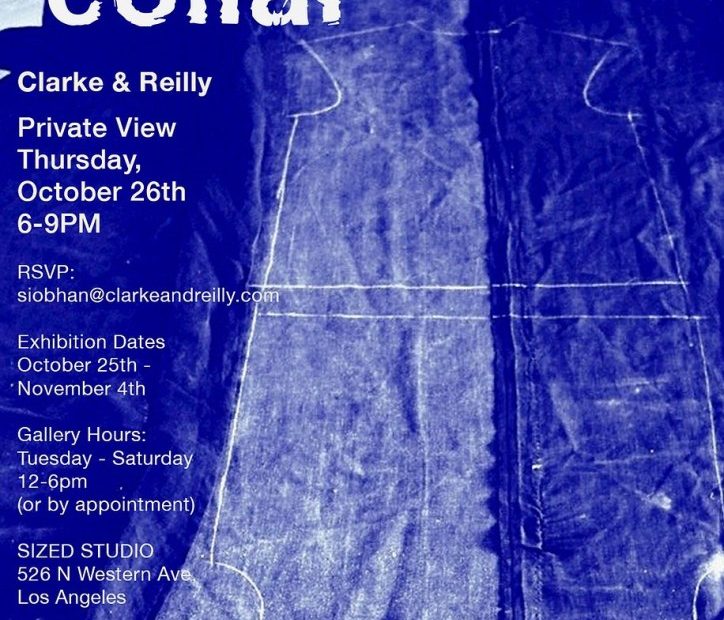

The artist duo known as Clarke & Reilly (David Grocott and Bridget Dwyer) saw this creative potential in the structure of a T-shirt and conceived of an exhibition called Blue Collar with the T-shirt at its core. On view now through November 4th at LA’s SIZED Studio in West Hollywood, Blue Collar consists of a space with 62 T-shirts hanging from the ceiling. The pieces on display are hand-sewn from indigo-dyed fabric spanning three centuries and sourced from various corners of the world.

“We just copied the classic American T-shirt, and that was it,” Grocott told me bluntly when he and Dwyer gave me a tour of the exhibition just before its opening. “I’ve always deconstructed stuff, and I had this huge piece of material, and I was thinking of how I could deconstruct it and make it individual in each piece. The fabric lent itself to this classic, basic shirt. It’s a very humble shirt, which kind of speaks to everyone.”

It’s the universal functionality of the everyday T-shirt that underscores the greater theme of Blue Collar as a reflection on the American working class, specifically within the Los Angeles Garment District. The 62 dangling T-shirts sway and spin slowly from strips of a painter’s drop cloth that Grocott cut up, creating a sense of movement and bustle reminiscent of a factory or warehouse. Meanwhile, a soundtrack composed by Magnus Vines pulsates in the background, serving as a sort of sonic poem that features samples from different cultures and nationalities. The result is an eerie, twisted sound that creates tension among the floating T-shirts.

“Our process is very much the idea that things have a life of their own, and one thing turns into the next,” Dwyer told me as she elaborated on Blue Collar’s origins. “That’s how David always works; this is his nuanced reaction to the working class in America versus some kind of political statement. It came out of walking around LA and observing all of these people that were working and making things happen.”

Even before the fully realized concept for Blue Collar came to Grocott, he and Dwyer had been working with the fabric in other ways, weathering and tinkering with it and using it in other shows. Most recently, they incorporated it into an installation at the Howard Hughes compound in LA.

The fabric is a stunning amalgamation of utilitarian material found in England’s Black Country, the French countryside, and the Northeastern US. These materials include sections of bedsheets and old sacks, peasant cuts, and farming cuts, some with old repairs and patches, some with embroidered details. Once stitched together, the fabric was dyed using indigo from India, the US, and Japan through traditional dyeing techniques.

With the patina of time, things become more beautiful.

Bridget Dwyer

“This textile has been with us in our practice for about five years, and the fabric spans 300 years,” explained Dwyer. “So these 300 years of fabric were all hand-stitched together and then dyed with three types of pigment. Now, we use them in different ways, like aging them out in a field. When we put them out in the field to age them, this wasn’t the project.”

To achieve different weathering effects on the fabric, Grocott and Dwyer stationed various sections of it in three separate locations on a mountain range in Northern California. One site had dappled light, another was hyper-exposed, and the third was on a hillside. One portion of the fabric was bolted around a large boulder that grazing cows butted up against with their immense long horns. Another was wrapped around large columns in the sun. The fabric was then left to face the elements for three months before Grocott and Dwyer made the trek back out to retrieve them.

“When David had taken the textiles down from this land, he was like, ‘I don’t know what I’m going to do with it next,’” said Dwyer. “I think a lot of artists work like that; it’s all about the process. One of the things that’s always in our practice is time wears beauty well. With the patina of time, things become more beautiful.”

This weathered indigo fabric is no exception, as the various results of the different elemental conditions range from a vast spectrum of blue hues to striking visual patterns like tie-dye-style stripes. So, while every T-shirt in the exhibition is sewn identically, they’re each distinctly unique. “They’re all naturally different as part of the process,” said Grocott. “They’re all meant to be individual.”

The finished product of Blue Collar is impressive in its own right, but it’s clear that Grocott and Dwyer care far more about the process and journey than any result. For the duo, the act of crafting and creating with textiles is the art. “We’ve been really lucky to work with people who hand dye and understand how to bring a fabric to life. There’s no Dylon or anything like that,” said Dwyer.

“This wouldn’t age like this if it were a Dylon; if it weren’t an organic, natural fabric dye, it wouldn’t look like this,” Grocott went on. “It’s got to be an organic thing. It’s got soul. You’ve got to see the person who’s done it, see the hand that’s done it.”

When I asked the duo what was next for Blue Collar, they seemed interested in installing the show at another gallery. However, something tells me they’ll be on to the next project, perhaps repurposing the T-shirts, creating something entirely new. What that will be doesn’t really matter, alluded Grocott. “It’s the unknown that’s the most interesting thing.”