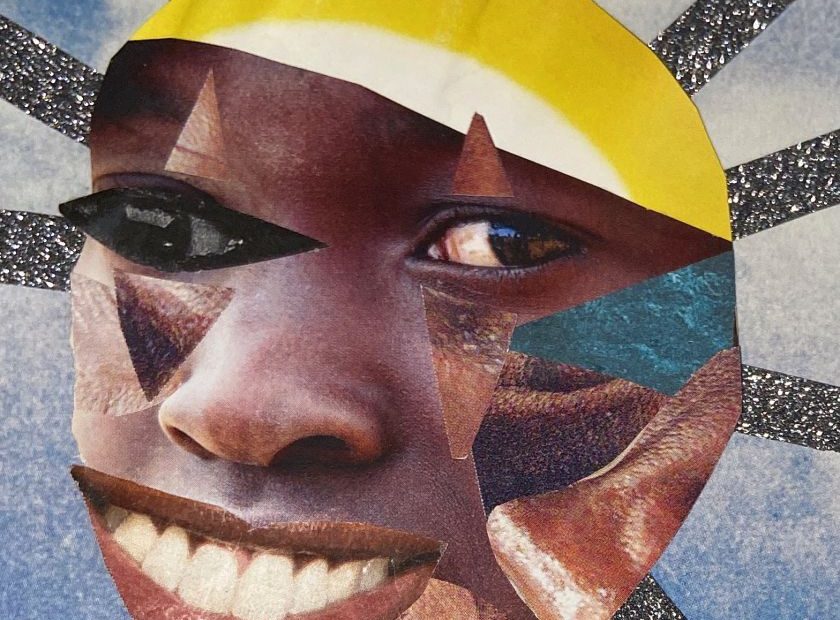

London-based artist, writer and publicist Funmi Lijadu tackles issues of identity in her tactile, surreal collages. We caught up with her to learn more about her work and discover how she’s worked with the likes of the Barbican and Tate Modern.

If you’ve got Funmi Lijadu coming to visit, you might want to hide your magazines and scissors. It’s a lesson her friends and family learnt the hard way, as she would often use these materials to create her incredible collages that tackle culture, gender and climate justice.

An English Literature graduate from the University of Edinburgh, Funmi brings a writer’s perspective to her art. Snippets of sentences and key phrases frequently jump out of her collages as she combines the beauty of the written word and aesthetics. This has led to her writing for publications such as Cosmopolitan, Metro UK, gal-dem and many more.

For Funmi, the pull towards creating collage art was magnetic. Stemming from her experiences as a young woman, where she would flick through glossy magazines, she eagerly wanted to be a part of the ecosystem that brought publications to life. So perhaps it’s no surprise that magazines would eventually become a source material.

“Collage, as an artistic medium, falls under the wide umbrella of mixed-media,” Funmi tells Creative Boom. “In reality, it’s an accessible art form that you can practice with materials that probably already exist in your own home. I love reusing paper materials, books, magazines, receipts, and posters and giving them a new life as art.”

Funmi began exploring collage as a medium during her A Levels when she would fill up her downtime by creating art pieces. From there, she started submitting to open calls at publications started by women and aimed at young women like herself. These included platforms like Leomie Anderson’s LAPP, the brand’s digital magazine, Tavi Gevinson’s Rookie Mag and DIY zines.

“It was so much fun, and I enjoyed the communities, conversations and energy around these platforms,” she reveals. “I put myself forward for loads of open calls, inevitably facing lots of rejection, but this made all the successes much more meaningful.”

Funmi singles out 2018 as her breakthrough year, as her submissions for the Tate Collective Black History Month Open Call were successful. Having come across the opportunity via Instagram, she was soon commissioned to make a collage responding to the work of American mixed-media artist Romare Bearden. “This encouraged me to keep proactively pursuing my art and writing.”

Despite scaling these heights, Funmi has stayed true to her roots and still primarily uses magazines, books and other paper materials to make her collages. These are then digitally scanned so that she can share them publicly. “I also make digital collages, sometimes from scans of 2D or 3D objects, as well as online archives and the internet at large.”

Outside of physical materials, Funmi is also inspired by conversations, loved ones and podcasts, not to mention the ever-useful shower thoughts and the internet-free moments on the London underground.

“I love the energy of certain historical movements in art like the Surrealists,” she adds. “Though women were overshadowed in the canon by the big boys of surrealism like Picasso, Salvador Dali and Pablo Picasso, women made significant contributions. Women like Dora Maar, Frida Kahlo, Paula Rego and more.”

She adds: “The work of living artists also inspires me, the work of my sister Kemi Lijadu, a filmmaker and DJ, Lynette Yiadom Boakye, and my amazing peers I work alongside.”

Art can often seem like an impenetrable, money-focused world to outsiders, so Funmi credits her dad, a collector interested in African art, for guiding her path. “His perspective is a highly economic view of art, so I think he has a more protective mindset where he knows how auction houses and institutions ultimately exploit artists, even the most powerful ones.

“I’m a professional hybrid for that reason, to use my talents to find multiple income streams. I did art GCSE at my secondary school in Nigeria and was discouraged by the narrow view of art held and reinforced by my teachers and their grading. I was force-fed the dreary, essentialist doctrine of still-life-obsessed realism and was made to paint even though that’s not my strongest ability.”

Funmi says she blossomed in her art through self-led practice, away from the constraints of academic study. “Art teachers can sometimes be the most discouraging – but there’s a world beyond the academy!

“I’m a big believer in the universality of art in the human experience and how it connects us all. In my experience facilitating art workshops in environments from Tate Modern to Barbican to LSE to secondary schools in Scotland, I put a lot of energy into being an encouraging teacher and facilitator. Art and life should be intertwined.”

And even though words play a big part in her work, Funmi still thinks images of humanity and human issues are the most powerful.

“That’s why when governments and institutions want to control narratives and minds, they cut internet access, monitor conversations, burn books and censor wildly,” she concludes. “We are strong as a collective when we recognise each other’s joys, pain, and desires. Words are powerful, as one type of action.”