This industry op-ed is by Joey Zeledón a designer, design educator, writer, and founder of Joey Zeledón Studio.

Be yourself. That’s what everyone tells you growing up. I never imagined such a simple notion could take almost 40 years to achieve.

Being myself is a radical act. That’s because I am trans.

I’ve been publicly existing as a trans person for almost a year since I shared my true identity very publicly through social media. But I’ve also publicly existed as an industrial designer for nearly two decades, having designed things like shoes for Clarks, furniture for Steelcase, lighting for Gantri, and kitchen products for OXO.

When I started earnestly exploring my gender identity and accepting myself, I discovered that my professional life as a designer had prepared me to face this new challenge. That’s because good design is also a radical act. It challenges you to engage with the world in new ways.

Through parallels in my experiences as a designer and as a trans person, I realized that design is actually trans. At the core, both design and transness are focused on transformation—defined by changing the appearance, composition, structure, or character of something. But the similarities don’t stop there. The process of a transgender person accepting themselves and expressing their identity is much like the design process.

Design is Trans Because it Creates New Narratives

The practice of design often results in new narratives for objects and experiences. Trans identity involves creating new narratives for yourself rather than using the old narratives you were given (from birth or otherwise).

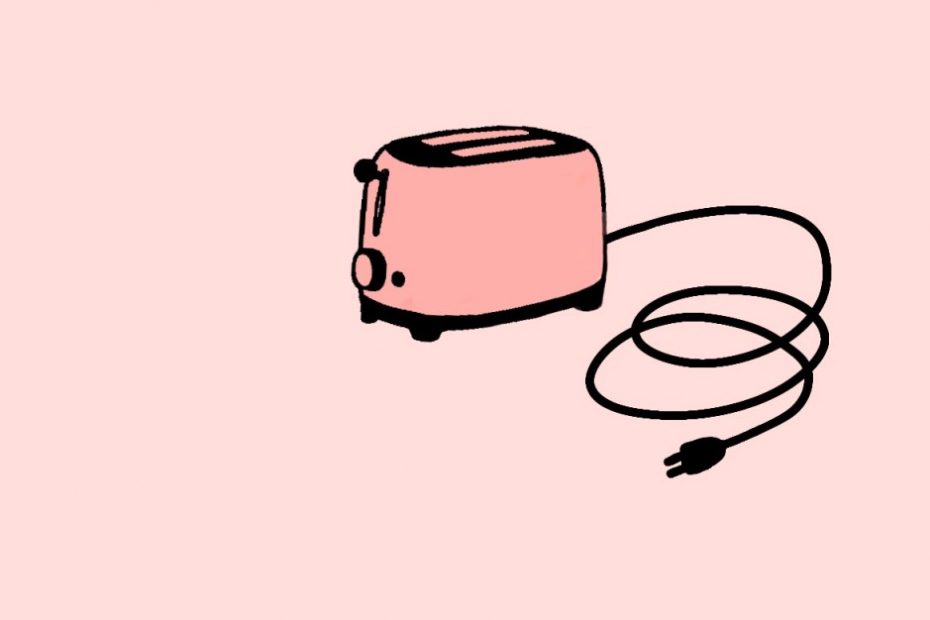

Language matters. When I design, I start with words. Language sets the foundation and tone for what the product will become. Before diving into form, ergonomics, color, and materials explorations, I must feel good about the product’s story. I look for fresh perspectives to reframe products by mashing up ideas in new configurations– a mix of recognizable with the unexpected– to create a narrative vision that drives my whole creative process. Furniture that prints. A closet you can sit on. A barista in your kitchen. A tanning salon for bread.

Not surprisingly, it was language that catalyzed my trans-transformation. For many years, the common language around transness repulsed me so much that I rejected the idea that I could ever be trans. It kept me from accepting myself until a more “user-friendly” language came along. There was a familiarity in the language that felt approachable, but there was also a newness that was exciting to reflect on. Could I be non-binary, gender-fluid, or trans-femme? Maybe I could be. The nuances of language mattered to how I saw myself positioned in the world and my personal narrative.

This underscores the significance of language in making sense of an identity, whether for an object or a human, which, in turn, drives the physical expression of that identity.

Through parallels in my experiences as a designer and as a trans person, I realized that design is actually trans.

Design is Trans Because it Expresses an Identity

Designers bring narratives to life through visual expressions that often consist of 2D and 3D forms, colors, materials, and finishes, combined in interesting ways that evolve how people see and use them. Designers intentionally use the affordance of familiar gestures and the symbolism embedded in our cultures to evoke specific uses and emotions.

In design, we strive to reflect the outside with the inside; this directly parallels my trans experience of striving to create a visual expression that is congruent with my gender identity (gender expression). I want my outside to reflect my inside. What does feminine and masculine look like in our culture? What signals my gender to society? Long hair or short hair. Dresses or pants. Heels or flats. Maybe somewhere in between. What resonates with me, and what doesn’t? What feels in alignment with who I am?

This object was assigned “toaster” at birth but identifies as something else—a tanning salon for bread.

I was assigned male at birth, but I actually have a fluctuating gender identity and, therefore, need to design a fluctuating expression. If I can design my gender expression to reflect how I feel on the inside day-to-day, I feel empowered.

Sadly, not all trans people have safe spaces to express their identity; I’m coming from a place of privilege. Their visual expression may not reflect their identity according to societal expectations of what it means to be masculine, feminine, or something else. And it doesn’t make them any less trans. An expression does not define your identity– it reinforces it.

Design is Trans Because it’s User-Specific

The practice of design considers specific user needs. The trans experience is similar. As a trans person, I design my transformation to fit me.

Just like there may be dozens of products in the same category for different target customers, there are so many ways that someone can be trans. For example, one could be assigned female at birth, transitioning to outwardly express a trans-masculine identity. Another could be non-binary and expressing a mix of masculine and feminine.

Just as designers tailor product personalizations to biometric variation and style preferences, trans people personalize their expression to a diversity of needs and personalities, much like cisgender people. Trans people may choose to express their identity via clothing, hormones, body modifications, voice training, none of these things, and more.

If you’ve met one trans person, you’ve met one trans person.

Design is Trans Because it’s Iterative

Designers iterate until we have an excellent product to share with the world. Trans expression is also a very iterative process for many, myself included.

As a designer, I go through countless make, test, and learn cycles, getting feedback from customers on concepts before converging on a final idea to invest in manufacturing. As a trans person, I have also gone through many make, test, and learn cycles as a way to explore which expressions align best with my gender and personality. When going from masculine to feminine expression or vice versa, I don’t want to feel like a caricature of femininity or masculinity. I’m always trying out different looks, testing how I feel in them before making the looks public.

I also realized that testing an MVP (minimum viable product) parallels the queer concept of “inviting in,” where you choose to invite certain people to share in your truth. Inviting in provided me an opportunity to build up support and confidence before sharing my truth more widely by publicly coming out.

One of the things I love most about design is that we introduce new things to the world. Over time, some of our novel inventions blend into our everyday lives. What was once radical becomes normalized.

Trans is Not Design

Design is, in many ways, trans, but not all trans experiences parallel design.

We celebrate designers for creating novel things that break the boundaries of the expected in the name of creativity and progress– we even win awards for it. But, transgender people, who are also dismantling norms and who have been around since before design became a profession, are met with mixed reception, to put it lightly. Trans people have come a long way in modern society, but we still have a long way to go, especially in the face of recent reactionary laws trying to eradicate us.

But I am hopeful. One of the things I love most about design is that we introduce new things to the world. Over time, some of our novel inventions blend into our everyday lives. What was once radical becomes normalized– i.e., it’s hard to imagine life today without airplanes and smartphones. I look forward to a future where transness becomes the norm, just like good design.

Joey Zeledón (he/they/she) is a designer, design educator, and author of Touchy/Feely and “Beyond the Black Turtleneck” and founder of Joey Zeledón Studio. They love to help objects find their higher purpose in life by creating aspirational narrative identities with congruent design expressions—is it just a chair or could it be a closet you can sit on? This essay is part of their larger written and visual exploration of how design is trans in an effort to promote dialogue and build empathy for trans experiences through the universal lens of design.