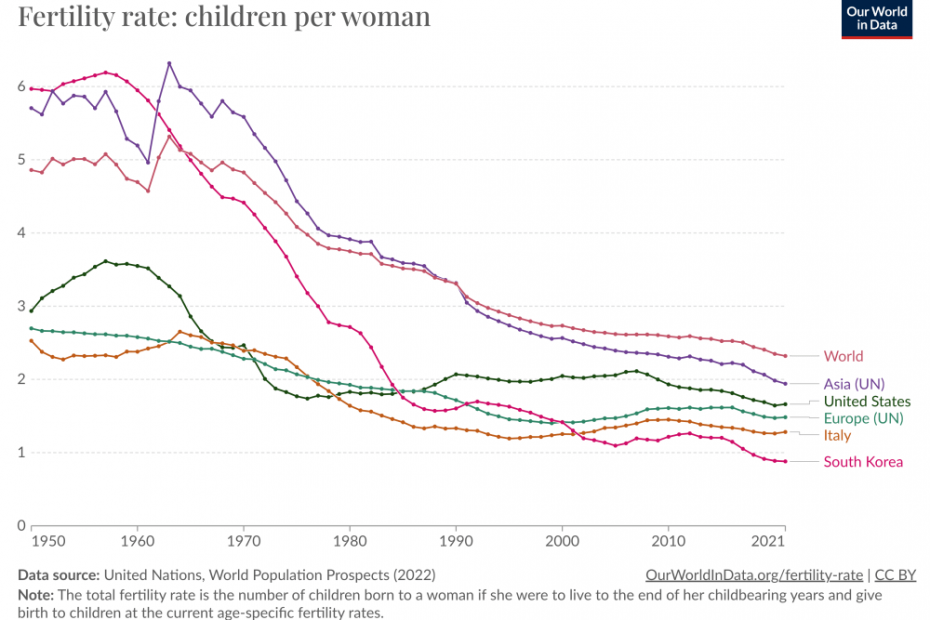

Worries over falling birth rates have replaced fears of the “population bomb.” Birth rates have noticeably cratered in Italy and South Korea but are declining throughout the developed world. Lately, it seems, the subject has been the topic of columns and blog posts by everybody and his brother. Here’s James Pethokoukis, here’s Ross Douthat, here’s Michael Huemer, and here’s a long list of posts from Robin Hanson.

Brink Lindsey has written two characteristically deep posts (here and here) in the context of his thoughts on “the permanent problem,” as well as an earlier one on the “global fertility collapse.” I could go on, but you get the idea.

These are all smart guys with good intentions. But they are also…all guys. They tend to downplay some crucial facts about the world in which women make child-bearing decisions. Men know these facts intellectually—they’ve heard the term “biological clock”—but too often don’t put two and two together.

Women over 35 cannot easily and safely have babies.

People build crucial human capital—including formal education, on-the-job skills, and professional networks and reputation—before the age of 35 and certainly before the age of 40. Men can devote these years to their careers and still easily and safely have children. Women cannot. They can only do so with the help of assisted reproductive technology, which is expensive, can be medically risky, and may not work.

Some careers are “greedy,” to use economist Claudia Goldin’s term. Greedy jobs are distinct from jobs that require child care during predictable work hours. They demand long hours, on-call work schedules, or frequent travel. They do not easily accommodate the demands of family life, which has its own greedy demands. Greedy jobs are often the highest paid or most prestigious in a particular field, industry, or society. For couples raising children, it’s generally the case that only one partner can successfully pursue a greedy job. The other will either take time out of work altogether when children are young or pursue a less greedy career. If both partners wish to pursue greedy jobs, they will likely not have children1. If a woman is pursuing a greedy job and her husband a regular one, kids are also less likely.

It’s also worth noting that, among developed countries, low birth rates are highly correlated with traditional attitudes toward motherhood and family life. The single best predictor of low birth rates in Europe is the belief that pre-school children are harmed if their mother works. It’s much more important than the price of childcare. See this deep dive by Aria Babu.

To get back to the Three Basic Facts, leave aside the fraught question of finding a partner and suppose an ambitious young woman meets and marries her ideal mate by her mid-20s2. Biologically she can easily have a several children. But to do so she must forgo developing vital human capital until she is in her 40s. Her male peers, meanwhile, will be building theirs. At 40, she will be the resume equivalent of, say, a 28-year-old man—but her education and skills will likely be, or be perceived as, out-of-date.

The traditional careers pursued by the mothers of the baby boom, such as teaching and nursing, are ideal for late reentry. (See my interview with Goldin.) Many others are not, including some, such as p.r., that may not even be especially greedy. The state-of-the-art moves on and, despite the law, employers often discriminate against people over 40, especially in entry-level positions. Robert De Niro vehicles notwithstanding, good luck finding an internship when you’ve been out of school for decades.

Pro-natalist policies that do not address the Three Basic Facts will be, at best, only marginally successful. Every time I read yet another article by yet another man who is ignoring these facts it makes me wonder what he was doing in his 30s.

Virginia Postrel is a writer with a particular interest in the intersection of commerce, culture, and technology. Author of “The Future and Its Enemies,” “The Substance of Style,” “The Power of Glamour,” and, most recently, “The Fabric of Civilization.” This essay was originally published on Virginia’s newsletter on Substack.

Banner image: In this 1903 illustration for Collier’s titled “Race Suicide,” Charles Dana Gibson, famous for his “Gibson Girl” illustrations, tweaked the concern about falling birth rates among affluent Americans of Northern European stock. (From my collection. See The Power of Glamour for more on the Gibson Girl.)

This includes single-sex couples like my sisters-in-law. It’s a matter of the division of labor, not gender roles.

On greedy careers, I always think of (a different!) sister-in-law, whose medical school professors encouraged her toward surgery. She said she’d like to talk to a successful woman surgeon who had a happy marriage and children. They said, “We think there’s one in Texas.” She became an anesthesiologist. (My brother, her husband, is a primary care physician.)

In case you’re wondering, I have seven sisters-in-law. I have three brothers and my husband has three sisters, one of whom has a wife. ↩︎For a discussion of marriage in this context, see this post by Alice Evans. ↩︎