Long before smartphones and digital watches, people relied on a curious invention to know the exact time: the speaking clock.

This service, accessed by telephone, connected callers to a live or recorded voice that announced the precise hour. The very first of its kind appeared in France on February 14, 1933, when the Paris Observatory launched a system that used glass discs synchronized with a master clock. By dialing a simple number, Parisians could hear a calm female voice tell them the time with absolute accuracy.

h/t: vintag.es

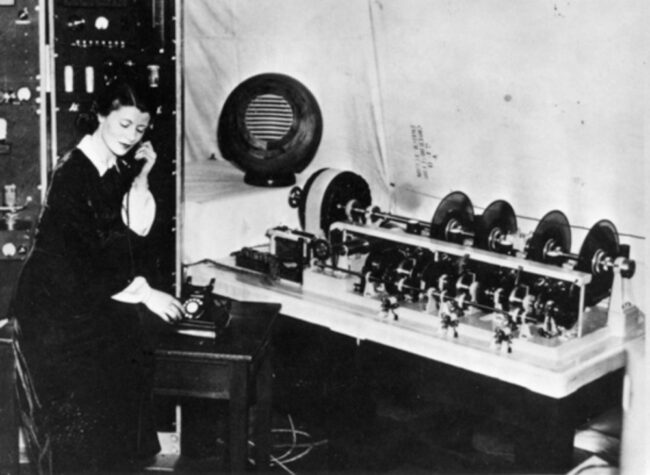

Britain followed a few years later, introducing its own speaking clock on July 24, 1936. Operated by the General Post Office, callers dialed “TIM” to hear the famous phrase, “At the third stroke, it will be…” The first voice belonged to Jane Cain, a London telephone worker chosen from thousands of applicants for her clear and reassuring tone. Behind the scenes, the system relied on optical film recordings and electro-mechanical timers to keep everything in sync.

Across the Atlantic, the United States launched its first automated time service in Atlanta in 1934, not as a government project but as a clever promotion for Tick Tock Ginger Ale. Entrepreneur John Franklin adapted Western Electric technology to create the Audichron, a machine that would soon spread across the country and become the backbone of America’s talking clocks.

Australia joined the trend in 1953, offering its speaking clock through the Post Master General’s Department. Callers originally dialed “B074,” later replaced by the now-famous 1194, and thanks to Telstra’s routing systems, the time was always local to the caller, whether from a landline, payphone, or mobile.

The technology behind these services evolved quickly. Early systems used rotating discs, film loops, or glass records to piece together words and numbers into seamless announcements. Later, magnetic tape and solid-state electronics improved reliability, while digital systems synchronized with atomic clocks brought accuracy down to the millisecond.

For decades, the speaking clock was part of everyday life. People called it to set their wristwatches, to time their baking, or even just to check if their phone line was working. It was a small but steady presence in homes and businesses, a voice that people trusted.

Eventually, the rise of mobile phones, the internet, and radio or TV time signals made the service less essential. Many countries retired their speaking clocks, leaving them as nostalgic memories of a more analog age.

Yet not all have disappeared. In the UK, the service still exists today—dial 123 and you’ll hear the time, synchronized with the National Physical Laboratory’s atomic clock, just as precise as ever.

The speaking clock may no longer be a daily necessity, but it remains a fascinating reminder of how technology once bridged the gap between science and everyday life, giving people something as simple yet vital as the exact time at the touch of a button.