Editor: Kim Tidwell

Creative Director: Jessica Deseo

The Greatest Show on Earth?

When a brand’s value is tethered to its ability to reflect an entire culture in a highly digital landscape fragmented by personalized algorithms, where does that leave typography?

All over the place.

Culture writer Kian Bakhtiari mapped out a few societal pinpoints in 2023 for Forbes, citing, “the abundance of information creates a poverty of attention. Finite time makes attention the most valuable commodity in the world. Some of the world’s biggest companies like Google, Meta, and TikTok trade in attention, not products or services.”

In recent years, documentaries like Netflix’s The Social Dilemma echo this, tracing how tech monsters design their platforms to keep us engaged in this loop, selling our attention to advertisers.

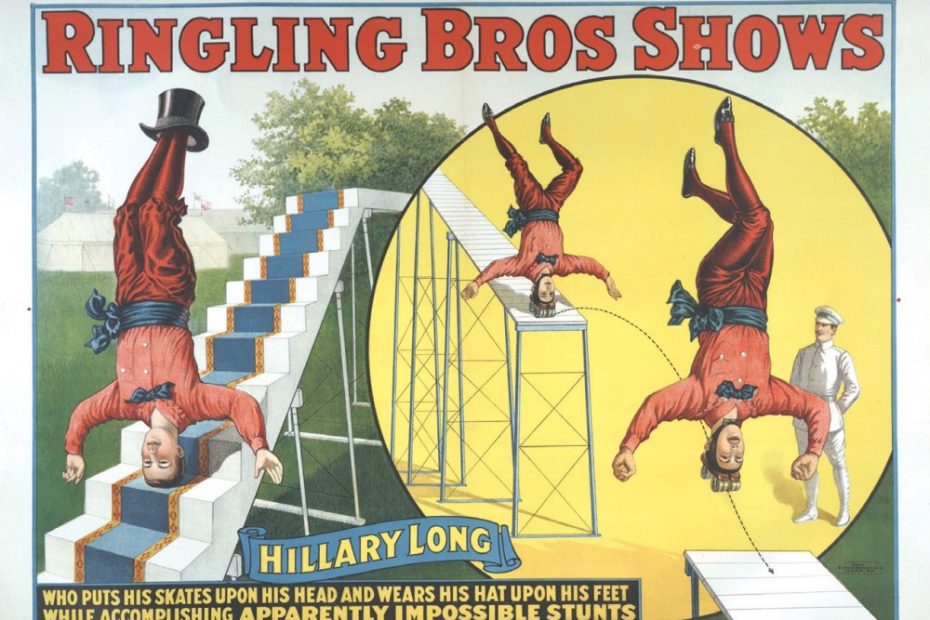

As we hitch our energy to social media, we ignore our addiction to it and other looming dangers like fossil fuels and artificial ignorance. Typographic feats in 2024 promise to soothe our vulnerability to the impacts of our dependencies. But will type prove to be more of a spectacle or antidote?

While our existence on this planet is mired in fog, the line for the greatest show on earth is queuing up: type in the age of Artificial Intelligence. As Rudy Sanchez reported from last year’s Adobe MAX conference, “If there remained lingering doubts that we’ve entered the age of A.I.-assisted design, Adobe’s MAX conference erased them.”

Designers will turn to type escapism. Typography will be the balm in an increasingly irritated society.

Letterforms will be more acrobatic—performing stunts, magic acts, and high-flying feats. Step right up; we are ruinously unprepared for the circus of type.

BOLD STRIDES, BOLDER TYPE: Activism & Social Justice

Connecting to a new generation means brands have to engage in more meaningful ways than simply offering a product or service. More conceptual forms of relevancy that consider community, social issues, belonging, and hyper-relevant content are emerging. Type is one supple mechanism to this end. Another? Design criticism.

The design arm of the creative agency Mother brought activism and social justice together in one inflatable reality called The Bliss Sofa. It’s a floating Swiss-Army-inspired sofa that converts into a life raft, complete with a paddle and emergency lights. With cushions upholstered in the same orange fabric used to make life jackets and an optional ottoman that doubles as storage, the piece is a cheeky critique of climate change oblivion and will come in handy when the glaciers melt. Mother aims to sell the piece and donate some of the proceeds to the United Nations Refugee Agency.

The Bliss Sofa exploration is in direct conversation with Mother’s rebrand of Brooklyn Org, which strives to bring a new voice to modern philanthropy.

According to Creative Director Kozue Yamada, “As we explored, we looked at a lot of different condensed typefaces for the wordmark. We were inspired by aspects of PP Formula but ultimately wanted to create something much more condensed, adding rectangular counters and ink traps to reflect the nuances of Brooklyn blocks and streets.”

With the inspiration supplied by Brooklyn’s dense city blocks, the team selected Community Gothic as the voice of the Organization. For Yamada, “We wanted to use a typeface which was born in America, specifically in Brooklyn. Community Gothic was made by Frere-Jones Type, who are based in Brooklyn – a few blocks away from us!”

Yamada also studied other typefaces in the social activism space for inspiration, like Vocal Type’s Martin, citing, “Brooklyn Org has a bold vision and big goals, so the wordmark needed to reflect that. We wanted the logo to feel big, substantial – like a place where people can come together. We wanted to distance them from the tropes of philanthropy branding and create something vibrant and new.”

Typefaces tied to social activism are emphatic, human, and designed for rally cries and anthems. It’s a tradition established by Angel Bracho’s Victory of 1945, printed in celebration of the Allied victory in World War II, and Emory Douglas’ graphic work for the Black Panthers as seen in his Free Huey posters. Today, this legacy of social activism continues in the culture and education sectors, with typography choices even more reflective of local culture.

Examples: Community Gothic by Frere-Jones Type (left), Alt Riviera by ALT.TF (top right); T1 Korium by T1 Foundry (middle); Resist Mono by Groteskly Yours Studio (bottom right).

A SPIN AROUND THE OLD BLOCK:

Neo Displays

Neo Displays are proliferating, particularly when modernizing long-standing institutions with precious heritages.

The image to the left was created in Midjourney with the prompt, “A spin around the old block Neo displays.”

Marked by a new spin on typography that pays homage to the neon lights and signs of yesterday’s entertainment districts, Neo Displays perform an intense balancing act between legacy and future impact.

The recently renewed identity for New York Botanical Gardens by Wolff Olins is evidence of this consideration, with a custom wordmark that is a confident, bold, and impactful embodiment of the organization’s call to action. The agency explains, “Doing right by nature can mean different things to all the audiences of NYBG: studying it, protecting it, learning from it, or simply enjoying it.” Ultimately, it’s a wholly unmistakable logo: warm, direct, and expressing a bit of attitude.

Similarly, Pentagram created a new identity for the Shakespeare Theater Company that expresses the ongoing relevance of Shakespeare while enhancing the contemporary spin that the theater brings to the Bard’s timeless stories. For instance, it frequently presents Shakespeare’s classic texts with a fresh angle, highlighting topics such as diversity, inclusivity, and tolerance while reflecting on universal themes including love, power, greed, life, and death.

Pentagram partner Marina Willer proposed a creative expression centered around the “interplay between a broad range of dimensions,” including classic and contemporary, artist and audience, stage and digital, entertaining and learning, intimate and collective, real and unreal – as a way of “reimagining stories from the past for audiences of the future.”

Examples: Cairo’s Film My Design by Maram Al Refaei (left); VT Fly by Jose Manuel Vega (top right); Team GB Paris 2024 by Thisaway and typographer Lewis McGuffie (middle and bottom right).

ARTIFICIAL HYPE:

A.I. Generated Type

Humankind is prompting Large Language Models (LLMs) and A.I. image generators to produce texts, images, and videos. Designers are also harnessing A.I., creating a space for the technology in established processes.

The image to the left was created in Adobe Firefly.

A.I. gives designers the ability to output letterforms quickly, while generating new imagined futures. Yet the natural eye does not easily distinguish between A.I.-generated media and truth. Enter the slippery slope, as generated images have immense value when they are so close to reality.

Challenging this interplay of type, form, and culture is Vernacular, an independent publisher run by Italian-Colombian graphic and type designer Andrea A. Trabucco Campos and Uruguayan graphic designer Martin Azambuja. In the sold-out first run of Artificial Typography, the established designers explore A-Z letterforms imagined by A.I. through the lens of 52 artists throughout art history.

In an interview by Steven Heller, the pair states, “There was a major breakthrough in 2015 with automated image captioning. As the name suggests, this study allows describing the content of an image in words. After that, it was natural to play the other way around and see what image would appear depending on the word selection.”

Prompting A.I. with ‘Letter R in The Equatorial Jungle, a painting by Henri Rousseau,’ emits a dazzling array of jungle fantasy Rs, with all the post-impressionist trimmings of the artist’s hand. Or ‘Letter B by Louise Bourgeois, crochet’ produces a row of bulbous, handknit Bs.

In the early stages of A.I., designers are primarily exploring text-to-image models, shifting their role slightly from creator to curator.

&Walsh enlisted the A.I. platform DALL-E in their recent rebrand of Isodope, a nonprofit striving to teach the benefits of nuclear energy as a clean, sustainable energy source in a climate-crisis world. Since Isodope’s classroom is virtual across Gen Z platforms like TikTok, &Walsh strategically met technology with technology. Using DALL-E enabled the design team to create visual potentials, and the outcomes also led to new possible directions. Ultimately, the collaboration arrived in a new dimension, literally. The bold, forward motion type of the wordmark and glitchy glow of the supporting icons paired with a dimensional grid bring an imagined future of galactic learning.

Jessica Walsh told It’s Nice That, “There will always be a place for designers and traditional craft to help shape the A.I. outputs and push it to realms even further than we could have imagined. However, there will be the option of spending less time on tedious tasks and more time on pushing the creative, the concept or the product.”

The big question is, will General Artificial Intelligence (GIA) ever allow machines to understand and contribute to the world without us? A.I. remains largely exploratory for now, but once it begins to create more compelling stories without any prompt, stay vigilant. Designers must stay ahead of automated intelligence and decide how to integrate it with their work.

A sampling of A.I. Tools:

DALL-E is a text-to-image prompt that generates images.

Alfont is an A.I. powered type generator.

Runway has a suite of imaging and motion tools.

Cavalry brings procedural and node-based design into 2D (previously only possible in expensive 3D software).

Adobe Firefly offers a host of generative tools for designers across the Creative Cloud (and many more on the horizon).

Monotype has launched a new A.I. font-pairing tool.

CONTORTIONISM:

Letterform Abstraction

The movement of illegible display typography has been ramping up for a few years. It will continue to do so with new technologies, though its origins predate humans altogether. In 2017 and 2018, archaeologists uncovered evidence in South African caves of Homo naledi, an early human ancestor (which lived about 335,000 to 236,000 years ago), who intentionally buried their dead holding writing tools and made crosshatch engravings in cave walls that predate earliest known pictorial rock engravings.

Hieroglyphics (c. 3200 BC–AD 400) advanced this ancient practice into a formal language that combined logographic, syllabic, and alphabetic elements, with more than 100 distinct characters.

Graffiti dawned in the 1970s with abstract letterforms, combining anonymity with original expression—the latter eventually canceling out the primary as viewers became more familiar with a particular writer’s style. Brands today are gunning for this more proprietary and signature approach to letterforms.

Wolff Olins used abstraction and motion to create a post-pandemic identity for Seoul’s Leeum Museum of Art, with convergence at its heart. The logo, designed to move, reads as an entity rather than a word, partly because it’s reminiscent of the building’s architecture. But look closer, and the forms begin to emerge: L-E-E-U-M. The interaction it inspires across several museum touchpoints is like what’s happening around graffiti in your neighborhood, inviting a closer look.

Graffiti is hyper-abstraction at its best, giving abandoned and forgotten spaces a sense of ownership. Designers will continue to mine graffiti not only for its wild forms but also for its originality and distinct letterforms. The more our eyes learn to read abstract type, the more we will see this approach realized in logos, campaigns, and branded content.

Past Examples: (Top series) Lance Wyman, symbol for the Metro of Mexico City, as seen in Graphis Annual 69|70, edited by Walter Herdeg, The Graphis Press, Zurich, 1969; (Bottom series) Subscription to Mischief: Graffiti Zines of the 1990s exhibition at Letterform Archive, featuring: Greg Lamarche/Sp.One (@gregbfb), original lettering for the answer key in Skills issue 4, 1993; John Langdon (@6ambigram9), original art for the Philadelphia T-Shirt Museum, 1988; Handstyle master Leonard “Jade” Liu.

Present Examples: (top) Channel 4 (Bespoke/House/Proprietary type); (bottom two images) Nike Pixo by Fernando Curcio drew inspiration from “Pichação” and Graffiti, which have long been integral to the urban landscapes of major cities and Nike’s visual world.

SIDESHOW SENSATIONS:

Type Oddities & Flamboyance

3D & Inflatable Lettering

Inflatables in design have become popularized through many moments in history. Felix the Cat appeared as a giant float in the first Macy’s Day Parade in 1924. Andy Warhol’s 1966 Silver Clouds floated in and around his factory.

Seventies conceptual art couldn’t get enough—from Antfarm’s “Clean Air Pod” to Yutaka Murata, Pavillon du groupe Fuji, Osaka (below). And topping the list are the notebook-perfected bubble letters of the 1980s.

There’s an inherent escapism in inflatable/3D lettering because it transports us to our happy place. It’s youthful, absurd, and playful. It’s soft, comforting, and cartoonish. It’s a style perfected by type design legend Ed Benguait. Responsible for some 600 typefaces, including his namesake Benguiat, he created classics like Bookman and Souvenir, not to mention his heavy-hitting iconic logos for Esquire, The New York Times, and more recently, Stranger Things. And if this last one seems hauntingly familiar, that’s because acclaimed horror author Stephen King used Benguiat’s self-titled font for many of his novel covers.

We have a lot going on in our world, and fonts with volume and mass meet the moment with a play on absurdity and innocence. Expect this style to pop up in music venue posters, streetwear, and edgier campaigns.

Past Examples: “WNBC-TV News 4 New York Designs for Promotion” mechanical, Ed Benguiat; Benguiat Bravado Black 10, Photo-Lettering’s 1967 Alphabet Yearbook, New York, 1967; “Fat Stuff” in hand-lettered Benguiat Charisma.

Present Examples: Wonka (not pictured); Nordstrom Rack (not pictured); Good Girl (top left); Nike Campaign (Flip the Game) (top right); Alright Studio: Luaka Bop Website (middle); WIM, HK (bottom left); RTS Cambridge Convention by Kiln (bottom right).

Polished Glitch

This nod to bringing textural noise to letterforms gets a modification with contemporary tools that bring a luster to grungy 90s graphics, as seen in the work of David Carson and the legendary Art Chantry’s work in the 80-90s Seattle music scene. Chantry famously quipped, “Grunge isn’t even a style: it’s a marketing term coined by Sub Pop’s Bruce Pavitt to sell punk music.”

We can trace Chantry’s exuberant work and what Chermayeff & Geismar and Robert Brownjohn did for the 1962 album cover Vibrations to 2023’s Spotify Wrapped graphics and a plethora of other glitchy cues surfacing in font design.

Examples: Territory by REY (Reinaldo Camejo) (top left and top right); Disrupt by REY (Reinaldo Camejo), guided by Martin Lorenz (middle right); Domino Mono by Sun Young Oh (bottom left); Powerplay poster by Jude Gardner-Rolfe (bottom right).

Type Rebirths

No other font family has endured through the ages quite like Gothic lettering. The neo–Gothic alphabet emerged from the Fraktur typeface, which was prevalent in Germany until the beginning of the twentieth century. Combining stable forms with unexpected hand flourishes, this ancient style continues to find relevance today. It’s remarkable to watch this old-world classic find a multitude of contemporary iterations, giving a personal touch and gravitas to digital fonts. We are seeing new forms of ornamentation rendered not by hand but by machine, making way for newer ultra-gothic fonts in editorial typography and logo design lettering.

You can see this evolution in a continuation of The Vienna Succesion’s creative glory, on display in Letterform Archive’s latest book, which reproduces all 14 issues of arguably the first modern graphic design magazine. More than a rich sourcebook of early 20th-century graphic trends, Die Fläche (“The Surface” in English) shows the lasting impact of this movement, proving that riotous color and flamboyant forms can—with a new twist—work beyond posters, endpapers, bookmarks, and playing cards.

In both cases, heritage typefaces reappear through the filter of type treatments that celebrate flatness, expressive geometry, and stylized lettering.

Examples: Fayte by That That Creative (top left); Grundtvig Typeface by REY (Reinaldo Camejo), guided by Leon Romero (specimen and inspiration on right); Rumble Kill by Invasi Studio (bottom).

Type’s expansion in the year ahead will be spectacular, with creative letterers embracing the elasticity of our current societal drivers: gender, demographics, and spirituality. With each of us in our bubbles of adaptive algorithms and varying social concerns, type must perform its greatest act yet: appeal to disparate individuals under one strategic banner.

Type is no longer about simple communication. Now, letterforms are chasing new soul-stirring ends that calm, enchant, thrill, humor, and mesmerize us.

A brand’s longevity requires future-proofing through inclusivity and storytelling, and type must encapsulate similar fluidity. Because we are increasingly a multidimensional and complex society, our letterforms are evolving into malleable crystalline forms through A.I. and other technologies that allow letters to quickly hop in and out of prompted scenarios. While Herman Miller is back in its Helvetica Era, other brands and institutions are embracing the new era.

Typography must be increasingly pliable, proprietary, astonishing, and marvelous. We’re all gathered under its big tent, seeking a bliss point that electrifies us. With a fuse lit by A.I., type is skyrocketing out of a cannon into the unknown, obliged to be distinct yet encompassing in one magnificent stroke.