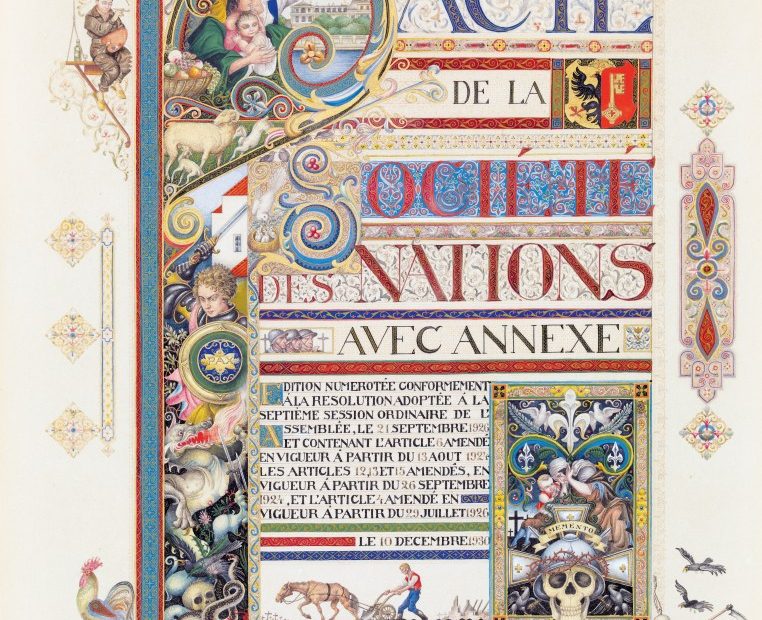

Frontice piece from Pacte de la Societe des Nations (Covenant of the League of Nations). Paris, 1931.

Arthur Szyk (pronounced “schick”) was a Polish émigré who was known in the United States for his cover portraits for Colliers and Time, cartoons for the New York Post and Esquire, and a large body of images on various Judaic and secular themes. As one of the most prolific visual satirists of his day, his World War II anti-fascist imagery had a visceral impact on viewers that was comparable to Goya’s Disasters of War. But Szyk’s mission went beyond topical satire; he employed art as an engine of spiritual transcendence and human liberation. A victim of anti-Semitism in his native country, he was forced to move to France and later to the U.S. Still, he fervently fought for a free Polish state as both soldier and artist, and later devoted his energies to freeing Palestine from British rule and building a Jewish state. Almost all of his works, even the numerous books of fairytales and fables he illustrated, were imbued with appeals for universal social justice. “To call Szyk a ‘cartoonist’ is tantamount to calling Rembrandt a ‘dauber’ or Chippendale a ‘carpenter,’” declared an editorial in a 1942 Esquire.

By the late 1970s, Szyk’s impressive body of work, which painstakingly wedded the highly crafted detailing of Persian-style miniatures to the symbolic acuity of iconic Renaissance masterpieces, was all but forgotten by contemporary critics, as impeccable draftsmanship had been made unfashionable during the ’70s and ’80s. Nonetheless, a Szyk renaissance seemed to be waiting for someone with a passion for his work. That someone was Irvin Ungar, a former rabbi, who in 1987 became an antiquarian book dealer and was dumbstruck by the work of the Polish émigré illustrator.

Since then, Ungar has devoted himself to Szyk’s resurrection. He founded The Szyk Society, a not-for-profit organization. He has used his pulpit skills to fire interest among scholars, promote history papers, and develop an ongoing exhibition program. The Society website szyk.org aims “to move Szyk,” says Ungar, “forward into public consciousness.”

He curated his first exhibition, Justice Illuminated: The Art of Arthur Szyk, at the Spertus Museum in Chicago. Numerous one-man exhibitions followed, each with different themes and works of art: Arthur Szyk: Artist for Freedom at The Library of Congress (2000), The Art & Politics of Arthur Szyk at The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (2002), a traveling exhibition to three cities in Poland (2005), Arthur Szyk: Drawings Against National Socialism and Terror at The German Historical Museum (2008), and Arthur Szyk: Miniature Paintings and Modern Illuminations at The Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Palace of the Legion of Honor (2011).

Pour Out Your Wrath from The Haggadah. Łódź, 1935.

Columbia Pictures (bookplate). New York, 1934.

“Art is not my aim, it is my means,” Szyk said about his metier. And this opens another important aspect of Syzk’s means of communication, an aspect of his pictorial language that has been not ignored but less celebrated than his pictorial means: The exquisite handlettering and gestural calligraphy that is such a seamlessly, essential part of his graphic output and visual legacy.

Herein is a range of Latin, Blackletter and Hebrew alphabets (he also rendered in Arabic and Chinese). These examples reveal not just his reverence for and mastery of classical lettermaking but a deliberate blend of the old and new. In The Great Halleil, the Hebrew letter is composed in such a manner that it is positively moderne. The dynamic layout of Le-Fikhakh-Therefore is the envy of any contemporary typographer. The duality of past and present goes throughout his work, which underscores the magnificence of Szyk’s unique hand.

Author’s note: Syzk’s lettering is one of the many forms discussed in Izzy Pludwinski’s excellent Beauty of the Hebrew Letter: From Sacred Scrolls to Graffiti.

The Szyk Haggadah, Le-Fikhakh-Therefore. Łódź, 1935

The Four Questions from The Haggadah. Łódź, 1935.

The Szyk Haggadah, The Great Halleil. Łódź, 1935.

Charlemagne and Jewish Scholars. Paris, 1928.

China from Visual History of Nations. New Canaan, 1947.

Illuminated envelope to former Prime Minister of Poland, Ignacy Jan Paderewski. Paris, 1932.

Illuminated letter to former Prime Minister of Poland. Paris, 1932.

Polish and French title page (Casimir the Great) from Statut de Kalisz (Statute of Kalisz). Paris, 1927.