Adrian Shaughnessy, co-publisher of Unit Editions (an imprint of Thames and Hudson), has a problem. He plans to make not one, but three books of work by Chris Ashworth, a former Ray Gun art director, editorial creative director and designer. The quandary: Can Ashworth’s work sustain the three-volume treatment?

Shaughnessy was turned on by Ashworth’s reliance on old-school methods. Per Ashworth, he has fused together “two creative journeys that I’ve been immersed in over the last two decades. I have a creative DNA which makes it hard to put into a traditional industry box and one that my clients see as a strength.” Thus, three volumes is a good solution.

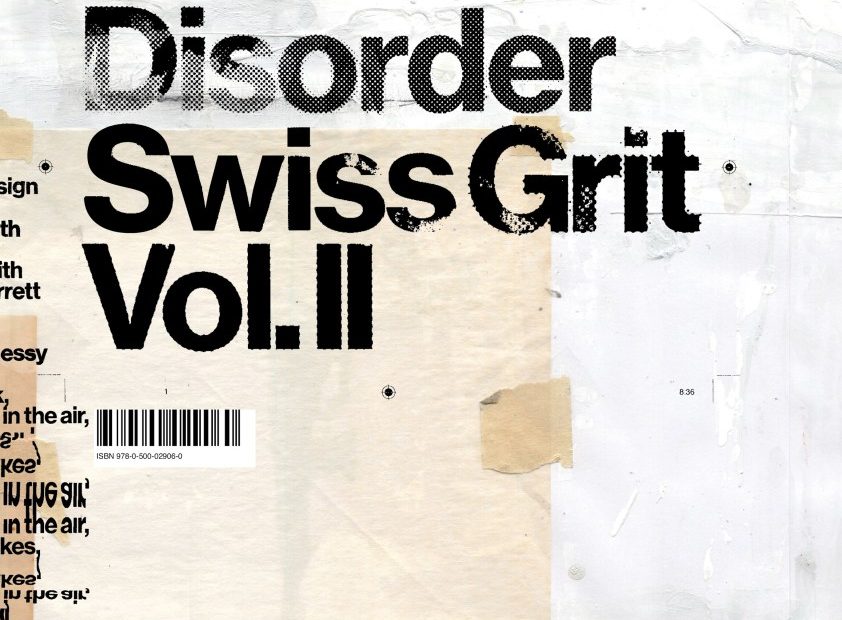

The first book, Disorder Swiss Grit Vol. II, is more akin to an artist’s book on steroids than a typical no-nonsense professional monograph. And as such it grabs the spotlight in the current chorus line of 300-plus-page designer showcase books published today. Another distinction is the majority of chaotic in-process images rather than pristine finishes. At first blush a reader might think this Ashworth is another artifice guy, but a second read-through will reveal a different truth. While he may be best known for replacing David Carson on Ray Gun, he has also lead strategic brand development campaigns, product launches and events for Microsoft’s consumer products. In this role he relished connecting multi-disciplinary teams across complex organizations, inspiring stakeholders and collaborating with agency partners.

Ashworth is a multi-dexterous designer who fuses “these creative experiences together to produce strategically sound brand creative with an innate focus on the aesthetic execution. [I] continue to follow my foundational ethos that’s rooted in human craft and the power of handmade creativity.” The designer’s hand is the special sauce in Disorder Swiss Grit Vol. II—so I asked Shaughnessy and Ashworth about it and the future volumes below.

Courtesy of Thames & Hudson.

Adrian, you’ve published a lot of big books over the past few years—and by that I mean page counts that have exceeded the average design book of the past. What are the reasons for (not only at Unit) these enlarged tomes?

Shaughnessy: I’d like to think big graphic design books are a consequence of the discipline’s maturity as a subject worthy of in-depth examination. But maybe it’s the result of graphic designers’ insatiable desire for images! In our case, the size and format of a Unit Editions book is determined by the subject matter. Most of our large-format books are monographs of designers with long and storied careers—Herb Lubalin, Lance Wyman, Paula Scher, Pentagram, the last of which merited a two-volume 1000pp blockbuster. These designers, and others not published by Unit Editions, fully deserve the “widescreen” treatment. But I admit to some unease about giant books and the ecological footprint they stamp on the planet. To counter this I’m currently working on a series of low-cost, small-format books that will sit at the other end of the scale spectrum.

Disorder Swiss Grit Vol. II fits into the former category. Is this a story that cannot be told in another dimension?

Shaughnessy: The size of the book was determined by Chris, and it’s only a fraction of his output. Stand by for volumes I and III. He’s from a different generation from those I’ve mentioned above, but he’s undeniably prolific and part of the reason for this is that most of his work is not client dependent. He is a stellar example of the designer as maker of self-generated work—and much of it made by hand! It’s also worth noting that he is simultaneously active on social media. The book works in tandem with the clips he posts on Instagram in a completely integrated way.

Chris, the title, like the cover, plays with language. What does Swiss Grit mean for you? And although you explain the “Vol. II” in your intro, I’d like you to expand upon what your trilogy, as you describe it, is intended to be.

Ashworth: Swiss Grit is a term that captures my two greatest creative influences. The former being the disciplined work of the Swiss international school of graphic design from the ’50s/’60s, which I was first introduced to, and immersed myself in, at York College of Arts & Technology from 1988–1990. Muller-Brockman, Hoffman and Ruder’s work being the leading lights, culminating in a thesis on Ruder which I still have in my archive. The latter being the imperfect counterpoint—the language of the street, the graphic design we see all around us out in the wild, shaped and ever-evolving through intentional and unintentional human interaction and/or natural elements. I find attraction and beauty in the imperfect and in a way it’s also a personal commentary, an observation on life itself and how I see the world and the things in it.

“Disorder” in the book’s title captures the duality of meaning within the term “Swiss Grit”—that cocktail of rigor and precision shaken up with some serendipity and patina. It also nods to an important musical reference—Joy Division. Music is at the core of how I work, and that particular lyric captures an important narrative for me.

In terms of “the trilogy”—Vols. I, II and III—this began as a modest book and rapidly became an epic tome. I wanted the book to be about the creative process as much as the finished work, and having such an extensive archive, the content dictated the outcome. I’ve always liked being led by the process, as it often takes me to interesting and unexpected places. With the heart of my output and my most recognized work being Ray Gun (1997—1998), it seemed an apt place to start Vol. II and run chronologically through to my current work.

The next book, Vol. I (1990—1997), is already in the works, capturing my early post-college rave and club culture flyers designed in the north of England, an independent book collaboration with the photographer John Holden titled Interference, and then my move to London in the mid-’90s, first at MTV with Tomato and Anton Corbijn, and then two early 1996 projects for Marvin Scott Jarrett—Blah Blah Blah magazine and the book Ray Gun: Out of Control.

In musical terms (Depeche Mode), Vol. II represents the more expansive “Music for the Masses” outputs, whereas Vol. I will capture the more claustrophobic Black Celebration period. As for Vol. III, who knows if I have an epic Violator left in me, or maybe my swan song will be more of a Memento Mori …

You ask what this trilogy is meant to be? It’s a call to arms—and fingers, hearts and minds. A stand against digital hygiene and the rise of the robots. A small celebration of handmade human creativity in the hope that it may inspire others. Put more bluntly, AI can kiss my art—I see no AI in creativity.

In your afterword, “Grit and Grunge vs. Digital Hygiene,” Adrian, you mention others who’ve transgressed in terms of typographic standards. You mention David Carson as the “most prominent grid-refusenik.” Where does he fit into the continuum of the work examined in this book?

Shaughnessy: There is an obvious overlap between Chris and Carson’s work because of Ray Gun. But it’s my belief that Chris’ work would have evolved in the way it has without the precedent set by Carson. Chris has rooted his work in Swiss Modernism, which he’s transformed into his own highly effective mode of expression. It’s as if Swiss Modernism is a boat tied to the harbor wall and Chris has unmoored it and let it drift out to sea. And of course, Carson was not the first to abandon the grid. I would cite two of my heroes, Willem Sandberg and Karel Martens, as exemplars of grid-free graphic expression. There are many others, Ed Fella, for example.

Chris, what are the reasons behind your transgressions? To me, your work bridges the road between computer-driven “new typography” and what Massimo Vignelli, in one of his less dogmatic statements, called painting with type.

Ashworth: My transgressions are unplanned and organic. On reflection, I’ve always been drawn to less populist culture, whether trends, gadgets or (insert your own suggestion here), as well as naturally wanting to make things by hand. For example, in the ’80s my friends all wanted Ataris or ZX Spectrums. I wanted to design the box covers for my VHS tapes. In my last year of design college, the Mac arrived and all I wanted to do was mess around in the metal type room. This continues today. So whilst I have a great passion and respect for the principles and outputs of Swiss design, the boat is always going to be getting unmoored simply because it’s innate and something that not only lights my fire but also something that we as humans need to draw on more—breaking free from constraints, liberating our bodies and our minds and getting away from screen dependency. But one cannot unmoor if one has not built a sturdy boat.

Lastly, in this technological moment we find ourselves in, I would say that it’s more important than ever to champion the craft of human creativity and inspire the younger generation to—as the lyric cries out—”let it out somehow.”

There is a generous amount of work-in-progress in this book. What determines when a piece is no longer in progress?

Ashworth: I find this question utterly fascinating. Firstly, to interject a little relevant context—having worked as a creative director leading in-house studios for large tech corporations over the last 25 years, I’m well-versed in receiving detailed briefs, experiencing rigorous client reviews and working through milestones towards senior stakeholder approvals. So, to answer your question specifically, from the experience of physically doing the work you see in this book, its “progress is finished” when I feel the response is resolved and whole.

Swiss Grit Vol. II is 488pp. If we ignore pages 350–435 (85 pages), as these are my own personal works—sound in print, typewriter poems and found type in the wild photographs—we are left with around 350pp of work. To summarize those pages, we have Ray Gun magazine, a Getty Images book published by Laurence King, a book commission by Michael Stipe published by LittleBrown, music commissions from Gavin Rossdale/Capitol Records, New Order/Mute Records and product campaigns for Nike and Adobe, all of which were paid projects, and whilst they didn’t necessarily have the layers and rigors of big brand client projects, they did involve client collaboration and dare I say “feedback” to an obviously much lesser degree.

Whilst the work-in-progress became “finished” when I felt it was resolved, there were also moments throughout these works when someone else’s perspective or feedback was interjected within the development, which had a bearing on the finished result.

It has been apparent that often the people commissioning me have consciously gone to lengths to avoid sharing their thoughts, with the desire to cultivate a pure-Ashworth response. For example, I remember diving into the Bush work for Gavin and sharing my initial outputs. He dropped me his thoughts in a couple of lines of an email, nothing more, but within those lines was a turn of phrase that became the beacon for the rest of the work. Having said that, Marvin gave me carte blanche on Ray Gun!

How do both of you feel about the counter-conventional approach of the book? Is it still valid to veer in this direction, or has time either made the “style” acceptable or a victim of changing tastes over time?

Shaughnessy: If by counter-conventional you mean the espousal of a handmade approach to graphic communication, or to put it another way, the rejection of the ultra-prevalent digital sleekness of most graphic design, then I think it’s what makes the book—and Chris’s work—a refreshingly vibrant blow against the prevailing digital orthodoxy. I also think his first-person text adds a note of real difference. It’s unusual for a designer to write so candidly about their work—the text is definitely “counter-conventional.”

All spreads © 2024 Chris Ashworth

Ashworth: Whilst I’m not against technology, primarily as a necessary production tool, I feel there’s a tendency to herd on the screen. Graphic design is becoming a (production) factory, conveyor belt industry. As Ferris Bueller once said, “Life moves pretty fast. If you don’t stop and look around once in a while, you could miss it.” We need to pause, and play, and discover. That’s what we humans do best.

The post The Daily Heller: Chris Ashworth Takes a Stand Against Digital Hygiene appeared first on PRINT Magazine.