Noir is my favorite color—but I could easily learn to love more after spending time reading Color Charts: A History by Anne Varichon, an anthropologist specializing in the implications of color and its cultural impact.

The moment I saw this gorgeous volume sitting on a pile in a bookstore, I turned all shades of green with envy. It is one of the most richly illustrated, beautifully designed and intelligently researched books of 2024 (a year that has already had its share of extraordinary art and design offerings).

Color Charts offers a full spectrum of inspiration as it reveals through text and image the various methods used to create an incredible number of colors and hues. It contains an awe-inspiring array of original writing and vintage texts on color creation and promotion through such artifacts as swatches, fabrics, charts and dyes. Sample books and notebooks are qualitatively reproduced, and the cover (designed by Katie Osborne) is a gem as object and document.

As Varichon writes, “For centuries, people have preserved documents containing color samples, creating a treasure trove for future generations of researchers.” This is among the most generous collections of those materials I have ever seen.

I asked Varichon to detail, anthropologically and viscerally speaking, her color theories, what color means, and how these cards, posters, guides and samples fit into human perception and behavior. This interview (and the book) was translated from the French by Kate Deimling.

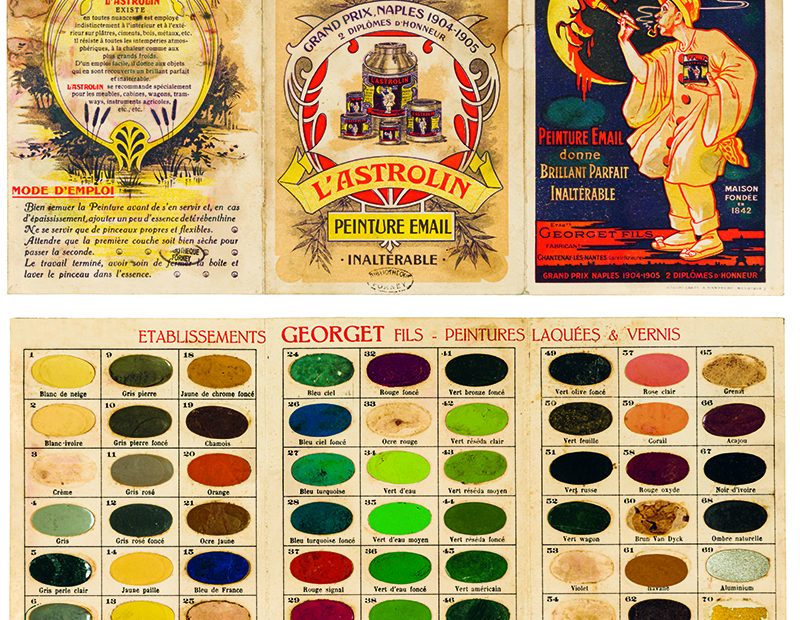

Astrolin Color Card, Établissement Georget Fils Peintures Laquées et Vernis, Chantenay-Lès-Nantes, c. 1906. Bibliothèque Forney, Paris.

What inspired your collection and scholarship in this unique realm of color?

In the 1980s, I curated exhibitions for various museums, including the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris, the Louvre, and others. Color came up all the time, but there were no books discussing the people who produced color or describing how and why, with what materials, and for whom color was manufactured. So I started doing research to explain the purpose of this strange thing, which is so hard to define, often requires great efforts to produce, and has little practical use, but still exists everywhere, and has existed since the dawn of humanity. In 1998, I published Couleurs, pigments et teintures dans les mains des peuples, an anthropological overview of the producers, materials, processes and uses of color, starting in ancient times and covering various cultural areas. This book is still in print and has been translated into several languages. The English edition is Colors: What They Mean and How to Make Them. I continued to do research in this area and gradually I had an intuition that in the Western world, color samples had catalyzed developments in science, technology and aesthetics over the centuries, while also causing crucial transformations in the way society thought about color. But I still needed to prove this hypothesis!

I’m impressed by how deeply you delved and how far back these go.

I started working on color samples in 2007, kind of feeling my way around, as often happens when you tackle an area that hasn’t really been explored. I was immediately charmed by these documents and their enchanting power, which was exactly the thing I wanted to try to decipher. And right away I was also so amazed by the variety, beauty and poetry of color charts that I wanted to share these documents (the vast majority of which had never been published and were inaccessible) with as many people as possible. That also meant giving readers ways of understanding these color charts, and a sense of how each one was part of the construction of a constantly changing relationship to color. This research took 16 years. Finally, the images of the color charts had to be perfect. Philippe Durand Gerzaguet, who took all the photos, managed to pull this off.

Color chart of silk velvet ribbons, G.G. & Cie, France, leporello, 24 x 13 cm, 31 panels, late 19th century. Bibliothèque Forney, Paris.

You have a section on naturalists using samples. How universal was this for scientists in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries?

Scientific disciplines, in the modern sense of the term, were for centuries essentially European. When color references were used outside Europe, it’s because they traveled with Western researchers. For instance, when Darwin traveled to the Madeira Islands, he took with him a copy of Werner’s 1821 nomenclature of colors that was completed by Syme. This allowed him to record the colors of the plant and animal species he sampled in his explorations. But many cultures never needed samples to observe and understand their environment and were able to use other methods to develop bodies of knowledge whose depth more than competes with modern science.

Was there a mystical as well as scientific interpretation of color for which color samples were used?

There have certainly been mystical interpretations, but I’ll just respond here to their scientific use: Yes, color samples were part of the rise of science in the West. In the hands of practitioners, such as dyers or painters, they were helpful tools well before the Enlightenment. They facilitated the memorizing of experiments and contributed to more precise communication of discoveries. So these color samples were crucial links, because they already implemented a logic that would ultimately be taken up and developed in scientific protocols.

The Chemistry of Dyers, New Theoretical and Practical Treatise on the Art of Dyeing and Printing Fabrics, Oscar Piéquet, 402 pages, Paris, 1892. Bernard Guineau collection, Ôkhra-Ecomuseum of Ocher, Roussillon.

You discuss nomenclature. How did colors get their names?

The lexicon of color charts depends on when the document was designed, by whom, for whom, and for what purpose. The first color charts made by naturalists often indicated colors by the names of the pigments that produced them (for instance, Minium in Waller’s work for a red obtained from lead). It was the same for manuals of artistic practices (Geele Orperement for a yellow obtained from orpiment in Boogert’s manuscript, for example). Dyers, who excelled at creating a wide array of shades, had to be more inventive from the start. Their color names constantly evoked references that embodied a certain color (Cabbage Green, Mouse Gray, and even Goose Shit). For instance, Antoine Janot’s brown shade called Cinnamon has no connection to the spice, but is the result of combining yellow, red and gray from weld, madder and oak gall. The terms would remain image-based, or even poetic, in textile color charts (with names like Dawn, Geisha or Zenith appearing in ribbon color charts during the interwar period). But chemists’ color charts would adopt intimidating yet very specific names from molecules (such as Rhodamine 6 J Extra in a color chart of dyes for Galalith from the 1920s). Only the color charts for decorative paints and artists’ paints would construct a descriptive and somewhat stable lexicon (Medium Turquoise Blue, Wood Tone, Train Car Green, etc.). Other names were inherited from ancestral pigments (Red Ocher, Ivory Black), even once they became exclusively synthetic. For instance, a gouache shade was still called Indian Yellow in the 1950s, when this pigment, suspected of being obtained from dehydrating cows, had already been replaced by a substitute a long time before.

Can you discuss the upheaval with synthetic colors?

To summarize in a few words: The discovery of synthetic dyes and pigments starting in the mid-19th century, combined with the growth of industrial processes, made affordable color available to everyone. Finally, color was not restricted to the elite. This is what I call the color revolution. The flipside of this is that the arrival of synthetic color wiped out the immense knowledge of colors from nature, first in Europe and then around the world, ultimately leading to a profound transformation of humanity’s relationship to color.

Linoleum Collection 1966-1967, Sarlino, Reims, France, 1966. Binder, 36 × 30 cm, 14 pages, Bibliothèque Forney, Paris.

Were color charts frequently revised?

Color charts could be reproduced identically for decades (such as color charts for Ripolin paint from the early 20th century). Textile color charts had to follow the rhythm of fashion, which was always changing. For instance, the ribbon color charts made by the Silk Federation changed every six months. Since the 1950s, color charts have been subject to the increasing speed that has affected all human activities. Today, they often last no longer than a butterfly.

Was there a universal language of color?

I don’t think there is a universal language of color. Its use is universal, yes, because color is a signal that is immediately perceptible, even from afar. So it is used everywhere to make visible—especially through clothing—categories of individuals (a wealthy person, a widower, a foreigner). But the way in which a community takes hold of color to express meaning depends on its particular culture at that time. Color is thus a parallel language for all societies, but specific to each one and constantly evolving.

Acid Dyes for Felt Pile, Base Colors, Société Anonyme des Matières Colorantes et Produits Chimiques de Saint-Denis, Saint-Denis, November 1930, leporella, Albi Couleurs, Association Mémoire, des Industries de la Couleur, Albi.

Credit: Anne Varichon collection, Sète.

How much of the colors used in textiles, paints, etc., came from flowers?

Dyes were produced from plants for a long time—not only flowers, but roots, leaves, bark, wood, and also berries. Insects and shells were additional resources for color. Minerals provided pigments, but even in prehistoric times, they were also formulated from the products of combustion, fusion or oxidization (charcoal, smalt, lead white, etc.). Cultures were very inventive, determined and brave in the ways they produced color from the resources found in their environment.

These charts from the past are such beautiful artifacts. Were they seen as art or purely functional ephemera?

For a long time, color sampling was private, remaining in the personal world of correspondence between scholars or inside workshops and factories. And even when the commercial world took hold of them in the late 19th century, color charts were distributed sparingly because producing them with samples of fabrics or feathers, or applications of paint or pastel, was expensive and labor-intensive. These rare, beautiful documents were preserved in workshops, stores and families. They inspired new productions and, over time, taught both the names of colors and ways of classifying them. So color charts developed as tools, lexicons, textbooks … and sources of dreams. Starting in the 1950s, when color printing replaced physical samples, color charts were distributed much more widely. Today, they are found everywhere, even on ordinary leaflets. Of mediocre quality and often ugly, these color charts have lost their poetry and sometimes they can’t even claim the noble function of tools.

Am I correct that during the world wars, color was muted, and after, color exploded?

Yes and no! Of course, restrictions on pigments and dyes due to wartime limited access to color, and during times of crisis, dark fabrics that could hide stains and signs of wear were emphasized. But the desire for color is also linked to customs, which evolve slowly. Right after World War I, everyone wore black because every family had to mourn someone who was killed in the trenches or struck down by the Spanish Flu. The postwar period of the 1950s was different: The rules about mourning were more flexible, and Western society was stimulated by the optimism of the period known as “les Trente Glorieuses” in France. Movies and magazines began to overflow with colorful images, the rise of ready-to-wear encouraged variations in clothing styles, and, finally, the petrochemical industry provided many innovative materials, pigments and dyes. Society could joyfully shift into color.

Of all the information that you researched, what was the most exciting surprise?

Great question. I think I was surprised every day during all my years of research as I discovered unknown color charts that had been forgotten in dark warehouses or had sat inert for decades on library shelves. Even the most insignificant ones had something to say about some aspect of the history of color. Of course, there were some I found especially fascinating: the color chart of silk velvet ribbons by G.G. & Cie, the color charts for artificial flowers, or those made by chemists during the interwar period, which are very humorous and aspired to add color to everything, from bicycle tires to soap. The major discovery of my research, however, was to realize that these innocent fragments of color had been the economic instrument, and then the political instrument, of hegemonic industrial development. By distributing color charts, industrial society not only crushed ancestral know-how everywhere, but it also globalized methods for classifying color that came from a way of thinking focused on quantitative analysis and productivity. Other concepts of color, which could be based on the depth and delicacy of shades or its relevance for a particular use, did not survive. The replacement of the product sample by printed color was their death knell, as color was now dissociated from its medium. The sensory experience was forgotten, and all the factors were in place for color to gradually be reduced to a bare reference number. I think that is where we are today. We have managed to “distribute the whole world with a single code,” as Georges Perec wrote in his essay collection Penser/Classer. Fortunately, the absolute necessity to escape from harmful overconsumption is beginning to make the pendulum swing back in the other direction. The future will certainly be full of surprises!