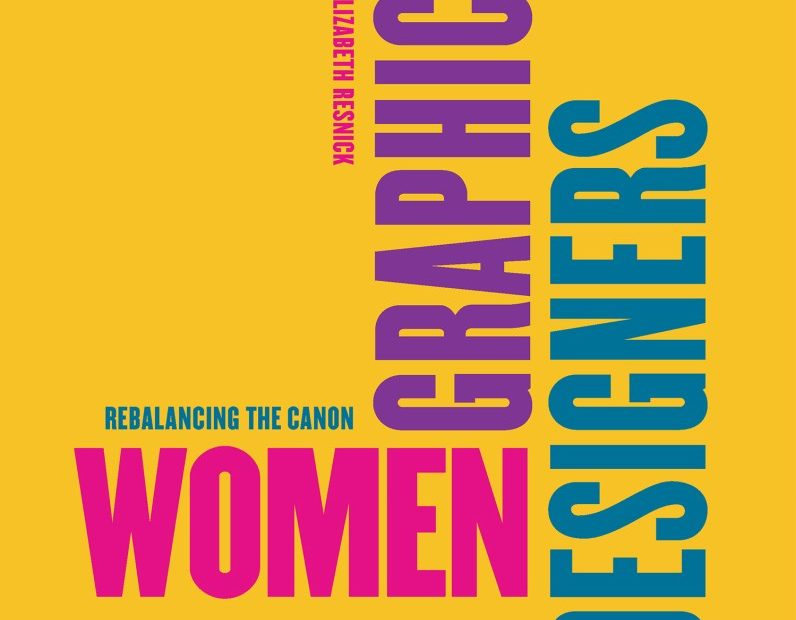

The first quarter of the 21st century has been a time of canonical change for graphic design, with an eye toward gender, race and nationality and those who have been omitted, forgotten or lost with the passage of time. Although innumerable women have played large roles in the history of design and typography, until recently the true extent of their collective and individual contributions has been marginalized—which is exactly what Elizabeth Resnick’s new book, Women Graphic Designers: Balancing the Canon (Bloomsbury), seeks to rectify.

Resnick has been a fervent advocate of social causes as viewed through the historical lens. She has curated major exhibits about how design has been used to fight the scourges of war and AIDS, and it seemed like only a matter of time before she’d focus on gender gaps in the history of the field. Below we talk about her book and how she curated a stable of contributors who have brought many of the lost or forgotten out from behind the curtain.

Farideh Shahbazi photographed in her office in Tehran, Iran, 2023. Photo: Mehrdokht Darabi. Image courtesy of Mehrdokht Darabi.

Farideh Shahbazi, two covers of Soroush magazine. Left: July 1991; right: October 1992. Images courtesy of Farideh Shahbazi.

There have been attempts to chronicle women graphic designers, who as you note are a huge demographic but under-represented in contemporary histories. What led you to the topic?

Backstory: In December 2014, Paul Shaw invited me to contribute a chapter to a proposed book he was editing on Modernist typographers. He knew about my interest in Jacqueline Casey (a MassArt alumna) from the piece I wrote for John Walters in EYE’s “Beyond the Canon” issue (Eye No. 68, Vol. 17, 2008). He asked if I would research and write about the origins of MIT’s Office of Publications, which employed both Jacqueline Casey and her MassArt classmate, Muriel Cooper. He introduced me to Robert Wiesenberger, a PhD student in design history whose focus was Muriel Cooper. Robert and I combined our research and knowledge to write the essay. Unfortunately, Paul decided not to pursue the book project. I submitted our manuscript to Victor Margolin at Design Issues, and it was accepted and published in the summer of 2018.

During this intensive research period, I learned about Thérèse Moll, a young Swiss designer who was invited to work temporarily at the Office of Publications in late winter 1959. She was credited by the staff for introducing them to Swiss design principles. At that time, I had just retired from my full-time role at Massachusetts College of Art and Design. I had the interest, and now I had the time to explore the stories of “forgotten women” in graphic design and share them with a broader audience.

Uemura Shōen portrait: Portraits of Modern Japanese Historical Figures, National Diet Library.

Left: Uemura Shōen, Board of Tourist Industry poster, Japanese Government Railways, featuring the 1936 Classical Dance painting. Kyodo Printing Company, Ltd. (n.d.). Right: Uemura Shōen, Classical Dance (also titled Noh Dance Prelude) painting, 1936. Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music.

Your book is composed of essays by educators, practitioners and historians who have studied and/or knew many of your 44 subjects. I must admit this is the first time I’ve been introduced to at least three-quarters of these designers, and an even larger percentage of the writers. What was involved in finding your subjects?

In late 2021, Briar Levit published her book Baseline Shift: Untold Stories of Women in Graphic Design History. By then, I had already written three articles published in Eye magazine: “The Enigma of Thérèse Moll,” “Jacqueline Casey: Design and Science,” and “The Quiet Confidence of Tomoko Miho.” I thought Briar’s book was excellent. In an interview with you, Briar said, “If I had my choice, there would be another edition of the book telling more unique histories with an even broader worldwide reach.” I thought to myself that, given the international contacts I had made through organizing and curating my international sociopolitical poster exhibitions, as well as my connections with the Design History Society (UK), I had the connections to help produce such a book. My process involved emailing my academic colleagues and friends, stating, “I am currently working on a book proposal titled Women Graphic Designers: Rebalancing the Canon, which will feature 40 essays, interviews or illustrated articles on underappreciated international women communication/graphic designers who primarily worked during the 20th and early 21st centuries.” I asked them if there were any women graphic designers in their culture they might be interested in researching and writing about, and if so, to please send a short narrative biography of that person. In some cases, I reached out to specific scholars I knew who had written about women in the field of graphic design or communication design. For example, Alice Roegholt had organized and curated an exhibition on the Dutch artist and graphic designer Fré Cohen. The exhibition book, Fré Cohen: vorm en idealen van de Amsterdamse School, was written in Dutch. I asked Alice to translate the article she wrote for the book, adding personal details that humanize the woman designer.

Once the book proposal was accepted, I gave each of my contributors one year to complete the essay. In some cases, the subjects who were still living were interviewed so the reader could hear their voice.

Karmele Leizaola photographed at Tipografía Vargas, circa 1950. Image courtesy of Faride Mereb.

Karmele Leizaola, spread for Elite magazine, circa mid-1950s. Photo: Carlos Alfredo Marín. From the National Library of Venezuela archive. Image courtesy of Faride Mereb.

How many of these women were unfamiliar to you when you began the project?

Perhaps half. That was the exciting part for me. I learned there are so many of these stories that need to be told.

Left: Gülümser Aral Üretmen, poster design that won an award in the Garanti Bank Poster Competition, 1952. Right: poster design for Denizyolları, circa 1950s. Courtesy of the Ömer Durmaz Archive.

Jane Atché, self-portrait with a green hat, 1909. Oil on canvas. Musée du Pays Rabstinois, France.

Left: Jane Atché, poster for JOB Cigarette paper, 1896. Color lithograph on paper. Musée du Pays Rabstinois, France. Right: Jane Atché, cover illustration, Belle capricieuse: valse par Gabriel Allier, 1904. Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

Your timeframe goes into the ’70s, with Postmodernism as a full stop. Why this time span?

The timeline for the book is based on the birth dates of the women included. Women born in the 1950s and ’60s are still working today.

In addition to uncovering and reintroducing Western designers, you’ve traveled to parts of the globe that are only recently garnering mainstream design attention. What governed your demographic choices for inclusion?

My goal was to create a book that reflects a global audience by including diverse perspectives, voices and experiences. I want readers from different cultural, social and geographical backgrounds to see themselves represented in the women and to understand the richness and complexity of their stories.

What did you want your writers to put forth in their essays? A scholarly or critical argument for each subject? A personal testament?

I asked all my contributors to write as much as possible about the “whole” woman, encompassing both her professional life and her personal life. In essays and articles about male graphic designers, the focus is primarily on their work and successes, with little to no attention given to their personal life, family or how having a family might influence them. For women, it is very different. As a reader, I am equally interested in how the woman managed to balance her work and her personal life.

Sujata Keshavan portrait, 2023. Image courtesy of Sujata Keshavan

Sujata Keshavan, branding for the Bengaluru International Airport, 2008.

What is your ideal outcome for this volume?

As I wrote in my introduction: “There are many compelling stories waiting to be told—to give all students and young designers the role models they deserve. Reading the stories of women with similar backgrounds, experiences or identities succeeding in the design profession can motivate and inspire underrepresented groups to pursue careers in the field. Astronaut and the first U.S. woman in space, Sally Ride (1951–2012), said it best: ‘Young girls need to see role models in whatever careers they may choose, just so they can picture themselves doing those jobs someday. You can’t be what you can’t see.’”

And finally, will there be another volume that carries the themes up to the present?

I could easily produce a second volume of Women Graphic Designers because there are many stories from the 20th century, various countries and cultures, that I couldn’t include in this first one.

The post The Daily Heller: Designing Women appeared first on PRINT Magazine.