Recently, I received an email from Rick Stark, a designer and art director of all kinds of things over the past 50 years. It reads:

I don’t know, Steven, if you would be as sad as I about Lou [Brooks’] passing [in 2021]. He was a friend and neighbor back in the times of madcap Graphic Artists Guild Halloween galas and such. We were occasional correspondents in the years after Lou and Clare left NYC; happily, launching his brilliant online museum allowed better opportunity for kibbitzing cross-country.

Inadequate to the task of eulogizing my friend here (Lou Brooks lived some high-octane lives), I write to share my concern that one of Lou’s great contributions to mankind (well, aged bullpen-folk, anyway) may soon be lost. The lights seem to be flickering over at The Museum of Forgotten Art Supplies, and I don’t know what to do about it.

If it’s a matter of money, concerned citizens should raise it. I will be at the front of that line. We warn our kids that what they put on the internet is forever, but it seems that’s true only if somebody’s paying the hosting bill.

I wonder if exposing this situation via any of your industry channels might raise consciousness to a) celebrate Lou’s estimable body of work, and 2) unblock whatever’s in the way and save the museum!

I too was a fan of Brooks’ work and his part in the all-artist band Ben Day and the Zipatones, which included Elwood H. Smith and Mark Alan Stamaty. Stark’s email inspired the following interview …

For the purposes of those who did not know him or his work, who was Lou Brooks?

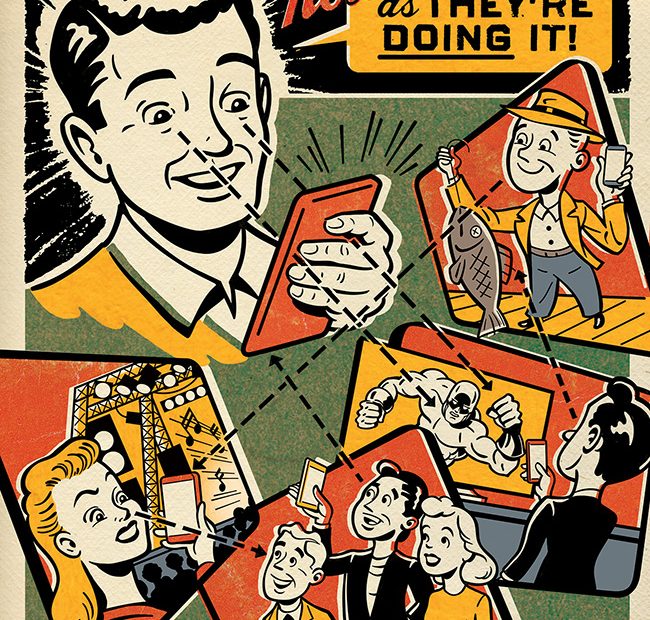

“Lou was the sociologic instrument through which ‘junk-art’ in print from the 1920s thru ’60s was elevated and concentrated into an idiomatic style exemplifying ironic/nostalgic American Pulp-Culture.” (Says me.)

How did you meet him?

As a very fortunate ’76 SVA grad, I was hired by Russ D’Anna to design magazines at Scholastic. My cubicle at 50 W. 44 was directly opposite the suite where Bob Feldgus and Bob Stein were doing the legendary pubs Bananas and Dynamite. I got to know all the regulars who came calling, not least of whom were the illustration team of Todd Schorr and Lou Brooks.

*

What was special about him as a person and an artist?

Lou was an erudite man wrapped in a larger-than-life performer’s sensibility—an illustration assignment was a stage call, a chance to wow the public, while his self-directed projects, ever-knowing, quietly dismember the Midcentury ad-speak and show-biz bombast from which they’re made.

Lou’s exaltation of the cheap and lowbrow—his ability to elevate it through an ironic lens and painstaking draughtsmanship—gave focus to the ubiquitous, anonymous, back-of-the-book “commercial art” that was part of life for most of the 20th century. Lou wrote his own material. He was a meticulous craftsman and had no objection to being a public figure. Was he a Warhol-like synthesizer of his surroundings? Was he Bob Fosse with a Sharpie? Should we anoint Lou Brooks the father of “Pulp Art”? He would’ve expected that.

I always recall his madcap sensibility. He was one of a group of young tricksters and retro illustrators. What were his times like?

Lou created his times.

While outings with close friends are nothing we’d want to publicize, Lou was an engine of community-building with the early Graphic Artists Guild, staging, with others, legendary galas at Limelight and Irving Plaza in the early ’80s. “Madcap” describes the mood perfectly … the fancy-dress Artist’s and Model’s Ball at Irving Plaza featured Lou fronting the all-cartoonist Zipatones band, plus Kid Creole or some similar August Darnell–like enterprise. Through a haze, I recall foam tombstones rollerskating past me on the dance floor, and from a balcony, an excellent Princess Grace, late of her auto mishap, waving as elegantly as the steering wheel around her neck permitted. Amid a sea of ambitious art student/lingerie models, we danced and drank and went home very pleased with ourselves. The times were good. For benefit of clients, friends and scores more, Lou rented out the third floor of Danceteria one winter Wednesday night, mostly, I think, just to celebrate … Lou. It was a time when drawing funny paid well.

By the late ’70s the National Lampoon and Playboy four-color guys and guys from the comics pages were getting mainstream work and could afford to have some fun and take chances. There was no better time to be an art director with a fat rolodex, no budget and a grand idea. …

In those days, in a certain light, it was easy to mistake Lou for Bill Murray. Lots of people around New York did, which became a thing. I was never sure if Lou loved or hated it. It did permit him plenty of room to improvise, and I know Lou loved that.

How did his website museum come about?

My detective skills brought me to “ZIMM” (Robert Zimmerman). Says he knows all and holds the keys.

I know you want to see it continue. What will it take to do so?

I would like the museum to become an asset of the SVA library, with plenty of attendant hoopla.

“ZIMM” says it’ll take $15 a month, though [it’s] likely not nearly that simple. Lawyers, probably.

How do you want Lou Beach to be remembered?

He must be recognized on his own merits. Perhaps someday.