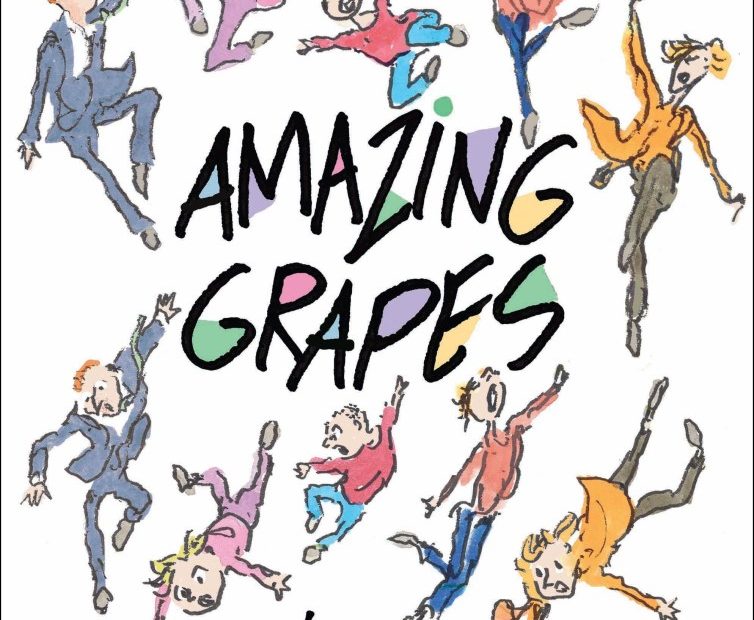

Jules Feiffer is 95, and his most recently published book is a graphic novel for children titled Amazing Grapes. It is a fantasy about a trio of siblings and multi-dimensional time and space travel, aided and abetted by various degrees of menacing monsters. Each episode in this complex story exposes the kids to untold dangers as they search for their mother, who is stuck between dimensions. It is a chaotic amalgam of characters and narrative twists, and Feiffer—who has written and illustrated conventional children’s books, among novels, plays, screenplays and all manner of imaginative endeavors—has yet to embark on a project as unique as this. He is 95, but making this book keeps him, he says, “7 years old.”

Over 40 years have passed since I worked with Feiffer on a collection of his weekly Village Voice comic strips. He was among the best political satirists. Around age 50, he turned his passion toward children’s books and graphic novels for adults. Now, he has almost completed his graphic autobiography. I can’t wait for it.

Recently I had the opportunity to talk with Feiffer about the work he is doing right now—and his surprisingly infectious optimism, despite suffering from an incurable degenerative macula disease that is stealing his eyesight and that of many other illustrators of his generation.

I finished Amazing Grapes, and I must tell you, I dreamed about it last night before this interview.

Yeah, what do you think?

I think it’s wonderfully absurd.

… And it was a lot of fun to do, too. My method of working has changed over the years since you and I [worked] together.

How so?

I don’t want to know what I’m going to do until I start doing it, and a voice says, “Do this, and do that.” I take instructions from some unknown voice that basically directs me. I don’t know what the story is going to be until the voice tells me what it’s going to be. I like to be ignorant of what’s about to happen—the book, in a sense, instructs me on how to write and draw it.

This is not your first graphic novel. How did this book come about?

I did a series of three noir graphic novels, and I felt it was time for me to write a story for children that was a little more complicated and a little more mysterious than the usual. I didn’t know quite what it was going to be. So, I started with the mother looking out a window, but I didn’t have a clue why she was doing that. Then the story started to tell itself. I had not planned on the interstellar travels or going from planet to planet. I just took instructions from the book and it told me where to go.

Did any of your editors have any input into the book?

Not really. The essential editor on these books of mine is my longtime editor, Michael Di Capua; Michael and I have had this lovely relationship since Sendak sent me to him 100 years ago, and so we trust each other implicitly. He knows how my mind works and how I think, and so he went along for the ride just as I was going along for the ride.

In the beginning of the book, you introduce the father, who simply leaves his wife and kids without any money.

The only thing I was sure of in terms of all of the characters, is that he was a bad guy. I didn’t know anything about the mother, other than she liked to look out the window and stare into space. Another thing I knew throughout is that there are a brother and two sisters and it’s their competitiveness and rivalry with each other that dominates over everything. So, they can be in the middle of space travel and awful things going on, but they’re concerned with what goes on in the relationship, mostly.

I thought that would be a lot of fun, and it was. And they seem to be looking for some sort of anchor with their mother, who doesn’t seem to want to be the anchor (we find out why later—she’s actually a creature from outer space and didn’t know it). At the end of the book, she has found her proper place, which is not to be with her children, but to be back in the planet that she fled from when she was little. But I didn’t know any of that was going to happen.

How did you decide on the title Amazing Grapes?

I was so affected when President Obama got up in the 2015 memorial for the Charleston church shooting, where the children were killed, and out of nowhere he started singing “Amazing Grace.” I mean, everybody in the country’s jaw dropped. I still have tears from that; I found it one of the most moving memories in my bank of memories, and it became a key signifier of the book. It’s what allows the characters to be free, and it’s a sign of hopefulness. It’s a sign of survival amidst all the perils that face you. It’s a sign about hope.

Why did you make such a sharp pivot from politics to doing children’s books?

I still deal with politics now and again. I’ve gone through so many shifts, changes and alterations and a sense of despair and discouragement—none of which I feel right now, by the way. Then there was my personal life, which was in repeated states of cataclysm. My work, whether it’s a cartoon, children’s book, play, a story that combines all of the above, is, in some ways, disguised as autobiography. I take what is on my mind and let all the things just happen, and they come out, and I try to structure them into a work of art and a work of amusement.

… And a work of exorcism?

Absolutely … a work of exorcism. But everything I’ve ever done is to get me out of the trouble I did. From the time I was a kid, cartoons [were] my own psychotherapy. You know, I’d be working through … well, I didn’t know what my problem was that I was working through. There’d be these aha moments over the years, and whether it was a children’s book or whether it was a play or whether it was a Village Voice comic, the older I’ve become over the years, knowing this self-analysis and feeling this way, the more playful my work has been to me and has become. And now, as much as anything else, it is a continual round robin of play. And when I made that discovery some years ago, it opened doors I didn’t even know were there, and I’m very grateful for that. And the doors will continue to continue to be open. I mean, I’m 95-and-a-half, and I’m still a 7-year-old boy.

One of your characters is a dog who is really a cat. In his dog guise, is it Virgil, the guide who takes us through your version of Dante’s Inferno?

I stole the dog from Walt Kelly [the creator of Pogo]. In his version, “man’s best friend” is leading people down the wrong path, and was always speechifying. And Kelly, who never had a nice word to say to me in my entire career, I decided to pay back by using his dog in my book. The dog is named Kelly.

Walt Kelly was also a strong voice against McCarthyism, wasn’t he?

Kelly taught me a lot about the cartooning world that I was finding myself moving into at the same time he was doing Pogo. He was the editorial cartoonist for the New York Star, which was the successor to the newspaper PM, and he was doing some of the toughest, most radical and imaginative cartoons on McCarthyism and the whole spirit of McCarthyism. He was much tougher than [Washington Post cartoonist] Herblock—and meaner. He just knocked me for a loop and strongly influenced the kind of politics that I moved toward as I was getting older and coming of age. Kelly was a great hero of mine.

Is it accurate to say that Amazing Grapes is a kind of coming-of-age book for the 95-year-old you?

You know, Steve, they’re all coming-of-age books. To me, they are all books of self-discovery. They all were stories I was telling, none of which I understood as I was telling them, that explained themselves to me as they, in a sense, wrote themselves and instructed me how to write. And that process is still going on. That is one of the things that I’ve learned over the years.

How has the macular degeneration changed the way you draw?

It doesn’t so much in some ways; as it always has been with my craft, the limitation becomes a plus. Instead of thinking of it as something that prevents me from doing what I want to do, I change it into something that frees me into doing something I’ve never done before, which is in many ways more innovative and fun—and fun is an important word in all my life. I’m out to surprise myself. I found a way to make them work for me, and I’m still doing it with the blindness. I had macular degeneration when I did Amazing Grapes but I hadn’t developed to a point where I thought I might lose my eyesight.

I was taking shots in the eye and stabilized during that period, and then it destabilized for a while, and I stopped taking the injections, because they stopped doing any good. But at the same time they allow me to do some of the best work I’ve ever done. So screw it.

The post The Daily Heller: Jules Feiffer at 95: “Doing the Best Work of My Life” appeared first on PRINT Magazine.