“

In their co-authored book Designed for Success: Better Living and Self-Improvement With Midcentury Instructional Records (MIT Press), Janet Borgerson and Jonathan Schroeder believe the story of instructional and self-improvement records adds an interesting aspect to the wider histories of the recording industry and popular culture—not to mention the American obsession with enriching life and experiences through mass communications.

This book is the final installment in a trilogy focused on vinyl records. “We’d been collecting unusual and curious record albums for decades—displaying them, discussing them and wondering about them,” they explain. “The ideal home, the ideal living room, the ideal romance, dance partner, honeymoon, family, not to mention the national Cold War victories in the kitchen and in outer space, all were visible, tangible, achievable, in the fantastical frame of the album cover.”

They continue: “We began incorporating Midcentury records into our research on consumer culture, tourism and place branding, ethics of representation, Midcentury Modern design. No one had drawn on Midcentury vinyl records in the way we were doing. Our colleagues said, ‘You should write a book.’ So, in Designed for Hi-Fi Living: The Vinyl LP in Midcentury America, we set out to change the way people think about vinyl records, revealing how record albums from the 1950s and 1960s offered postwar America Modernist visions and alluring lessons for achieving cosmopolitan and contemporary lifestyles fueled by a consumer culture of options, choice and consumer sovereignty.”

The second volume, Designed for Dancing: How Midcentury Records Taught America to Dance, featured the fun, colorful and sometimes provocative dance records—from the waltz to Watusi, square dance to Swim, polka to hula—filled with vibrant, sensual and seductive poses and personas. Soundtracks for dancing, but also soundtracks for dreaming, the records tell tales of American identity, becoming aspirational instruments for the fulfillment of national fantasy.

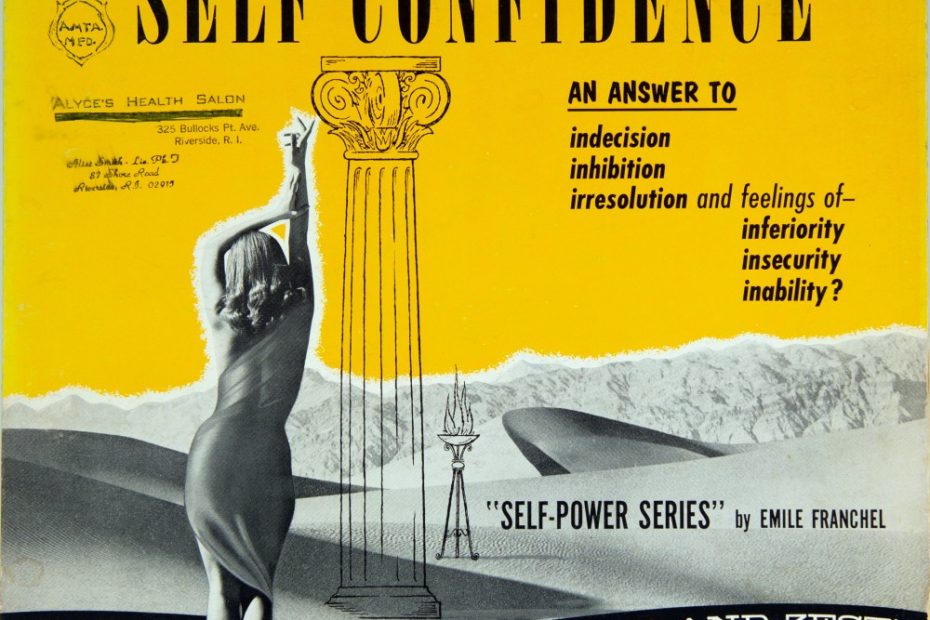

The final book in the trilogy, Designed for Success: Better Living and Self-Improvement With Midcentury Instructional Records, examines the ways in which these LPs—whether for salesmanship, speed reading or sports—express core values of U.S. culture, including self-reliance, opportunity and upward mobility; embody the self-help movement’s focus on personal improvement; and illuminate that fundamental American notion of self-motivated success.

Together, the three books simultaneously explore the art of forgotten Midcentury album covers, including the photographers, artists and designers who created a visual icon, and a national vision, that lives on today.

Here the authors talk about the last of their trilogy.

I am familiar with some self-help and betterment LPs of this period. Did the phenom start in the ’50s with records?

Actually, way before that, at the dawn of the phonographic era! Soon after inventing the phonograph in 1877, Thomas Edison sketched out what he perceived its most promising uses. He thought of recording business letters for dictation. He emphasized education, recording books and music and important lectures. In other words, Edison imagined phonograph records as instructional technology, and records indeed played a long-standing role in the instructional genre.

During our research in the Hagley Museum and Library in Delaware, we found a 1901 Victor Talking Machine advertisement for instructional records. A young girl stands next to a phonograph and the marketing slogan declares the machine’s usefulness for “listening and learning.” Early uses also included recording sales pitches and political speeches in a proto-advertising format. The corporate applications of recording technology, such as dictation, did originally attract pioneering firms in the recording business—for example, Columbia—but such companies soon realized that they were in the music business. Maybe now it seems unsurprising that entertainment surpassed instructional use of recordings.

Still, in the postwar, Cold War Midcentury era, vinyl discs housed in these meaning-redolent sleeves provided not only music, but also carried forward Edison’s initial inspiration. Vinyl records, as the latest content delivery technology, proved a key distribution format for self-help, self-improvement and instruction. A 12-by-12-inch art, design and information object. We consider instructional records fascinating anthropological artifacts that speak to fundamental and emergent U.S. attitudes, beliefs and values.

How did the genre begin?

In the early 1900s, Columbia promoted records for learning how to dance. Language records were another mainstay. An early instructional “hit” was celebrated baritone Oscar Saenger’s vocal training records—a complete course of vocal study for the tenor voice released on Victor records in 1916. A 1918 gramophone ad from Victor emphasized “the educational potential of its product in helping to teach roller-skating, calisthenics, kindergarten games, penmanship, maypole dancing, typewriting, something called ‘girls’ classes in rhythmic expression,’ wireless telegraphy to the Army and Navy, and French to the doughboys, all of this in addition to the history of music.” In 1922, Victor introduced “Records for Health Exercises,” paving the way for Midcentury albums like Bonnie Prudden’s Keep Fit / Be Happy, Debbie Drake’s Feel Good! Look Great! and Indra Devi’s Yoga for Americans.

Particularly interesting was the music appreciation genre, as a response to criticisms that phonograph recordings would dumb down the U.S. citizenry. Bringing classical music to the forefront seemed to be key.

From the examples in your book, it appears every subject was covered. Was this in place of or in addition to self-help books?

The presence of the expert’s voice in your own living room provided a bit of excitement, the sense you were learning from a key practitioner of outboard motor boating, hypnosis or jazz drumming. They were speaking to you. Records were repeatable, so you could listen again and again, whenever you wanted, as you cleaned up the kitchen or relaxed in the recreation room or focused on finger patterns at the piano.

Some instructional text typically appeared on back covers or in liner notes and enclosed pamphlets, but several albums in Designed for Success had companion books you could buy: Hugues Panassié’s Guide to Jazz, for example. The LP covers of Indra Devi’s Yoga for Americans and Napoleon Hill’s Think and Grow Rich both include small images of the related books. Two of our favorite LP covers, from Music Minus One’s “Adventures in Good Living” series, feature a special cutaway inset frame for a small Bantam recipe book—one a guide for mixing drinks, the other for Italian cuisine. So, these records came with books integrated into the cover design.

What was the story behind the music discs, like À La Carte: Music for Cooking With Gas?

Notions of self-improvement, progress and success often rely on understandings of human potential, and this potential can be unlocked or held captive. Mood and mindset are seen as keys to expanded perception and achievement or, alternatively, impediments on the path to success. Altering the mind, adjusting attitudes, controlling thoughts—these are mainstays in self-help teaching and advice.

And the Midcentury vinyl record might offer access to which productive mind-altering elements? Something that creates an environment, a setting, a soundtrack for success? Not only expert voices and spoken-word lessons, but music. Music for relaxation, music for studying, Music to Help You Stop Smoking. One album proclaims, “Affect your emotions through music,” and takes the listener from slow dirge on side one to swiftly ascending celebratory strings on side two. We included the RCA Victor series Moods in Music LP, Music for Courage and Confidence, that features a lone stargazing climber cresting a mountain top and lots of harp-plucking positivity with back-cover inspirational quotes from Thoreau and Longfellow.

And, why not? À La Carte: Music for Cooking With Gas. We like the suggestion that a turntable next to the shiny stovetop can keep the cook cool and the saucepan simmering. The medium pink and raw red typography on the album cover welcomes listeners to a meaty meal of “music that’s rare and well done!” Mastering that perfect sear on a steak implies the magic of new culinary methods and equipment styles, and Caloric “offers the very finest in gas ranges to ensure complete flexibility in kitchen design.” Keeping up with consumer demand, the company offered a kind of á la carte menu of colors, sizes and oven and cooktop arrangements to suit individual tastes and needs “when you dream of a new kitchen.”

A thin red line sets off the album’s titles against the cover’s white background, echoing print advertisements of the era; and below, vibrant illustrations of Caloric appliances pair with detailed insets presenting tempting outputs: cakes, cookies, steaks and ham in flower-bedecked homey arrangements. The “ultramatic” countertop range’s sleek wooden handle provides a distinctly Modernist design touch. No recipes or explicit instructions, just the subtle suggestion for acquiring a hi-fi set for the kitchen.

Music appreciation and music education records were often simply music: Let’s Get Acquainted with Jazz … for People Who Hate Jazz!, 4 Lessons in Jazz that sampled jazz genres through Art Blakey Jazz Messengers and the Detroit-based Australian Jazz Quintet. Classical Music for People Who Don’t Know Anything About Classical Music presents samples of orchestral pieces, but no helpful hints on how to listen. All of these were perceived to provide not just entertainment and pleasure, but also entrée to groups, or connections to individuals, who might be key to impress on the path to inclusion, promotion and success.

What were the major record labels?

Thousands of instructional titles were produced by major companies like Columbia, RCA and Warner Bros., smaller specialist firms such as Carlton Records and Conversa-phone, as well as numerous releases on private labels for company training programs, and records pressed for product promotion.

Generally, though, in contrast to the world of sales charts, hot 100 hits and pop stars, instructional records often appear as homespun productions and personal missives of advice. Some instructional titles feature famous spokespeople or recognized experts, and the most well-known how-to releases generally had some connection to a celebrity, but not necessarily to a big label. Jack LaLanne’s Glamour Stretcher Time was self-produced and capitalized on his popular television show in the late 1950s. Learn Tennis With Arthur Ashe featured the well-known sports star on an apparently one-off effort from Manhattan Recording Company.

A few instructional LPs sold well, such as, Bonnie Prudden’s Keep Fit / Be Happy on Warner Bros. and Play Electric Bass With the Ventures on Dolton Records. Vinyl records offered a convenient way to learn to play musical instruments. A typical learn-to-play album included musical tracks that left one instrument out—so the listener could “fill in” by playing guitar or saxophone, for example, along with a band. Music Minus One emerged as a leader for such “play-along” albums, and released hundreds of titles. Other offerings included Young Violinists’ Editions from Remington Records, a short-lived label that nonetheless benefited from covers designed by Alex Steinweiss. Columbia Records introduced “Add-A-Part” records in the 1940s but didn’t continue the line after the LP was introduced. Savoy Records released a “Jazz Laboratory” series of Do-It-Yourself Jazz records featuring pianist Duke Jordan with a quartet playing on side one and the same songs, but without the saxophone, on side two. Jamey Aebersold’s “Play-A-Long” discs reportedly sold millions of copies. They are still available, but only on compact disc.

Music Minus One’s catalog of music instruction records have sold in the hundreds of thousands. Music Minus One’s founder, Irv Kratka, a jazz enthusiast who produced his first record as a teenager, also ran Inner City, Classic Jazz and Proscenium Records. Dubbed “the godfather of karaoke,” Kratka released hundreds of Music Minus One discs. He recruited top names to play on their records, including first chairs at leading American orchestras and top names in jazz, including Max Roach, Stan Getz and Hank Jones.

In the 1960s, New York’s famous FAO Schwartz toy store carried records and featured a selection of instructional titles in their catalogs. Popular titles included Steve Allen’s How to Think, which introduced the younger set to the brain’s functions and basics of critical thinking and Sets: The Language of Mathematics, part of a mid-1960s series from New Math Records. FAO Schwartz also sold Music Minus One titles along with music instruction records, spoken-word recordings from Caedmon Records, and Peter and the Wolf albums, all in a separate record department.

I love the Dr. Joyce Brothers record cover. She’s so glamorous and the type is so Midcentury. Who determined the design schemes?

You’ll know her story—Joyce Brothers shot to fame by winning the popular television game show The $64,000 Question by answering questions on boxing. With a doctorate in psychology from Columbia University and her winning public persona, she launched the pioneering The Dr. Joyce Brothers Show in 1958. The show’s themes included sexual satisfaction (for women) and menopause, psychological perspectives on children, love, marriage and sex, all of which were considered a bit racy at the time. She wrote a syndicated advice column that appeared in hundreds of newspapers, and appeared often on television and occasionally in films into the 2000s.

On the cover of her Dr. Joyce Brothers Discusses Love-Marriage-Sex record, her toothy smile, her big light eyes stylishly made up, with flawless complexion, lend a glamorous appearance. The black-and-white album cover photo depicts her as an actress or model. But we could find no indication of who took the photo or designed the cover, like so many of these instructional recordings. (This album has aged better than most of the Midcentury marital harmony records we’ve heard.)

Who were the major record cover/sleeve designers?

Interestingly, sadly, much record cover design from these labels was anonymous. A record label’s art department might get general credit. A design firm such as Three Lions or Studio Five or Pate/Francis and Associates occasionally appears. Photographers might get a credit line, and over the course of the trilogy we gained familiarity with Wendy Hilty and David Hecht, who shot many covers for labels such as RCA.

From the design of the albums, there was certainly a “commercial modern” aesthetic—for instance, the Winning Bridge record is right out of the Bauhaus stylebook. Was this just the style of the day, or something more strategic?

As you might imagine, Midcentury album covers often drew on design trends of the era. You see photography coming in and largely taking over illustration. The use of distinctive colors, strategic object groupings and striking clothing styles expressed an aesthetic moment. For example, we like the modern color blocks of titles such as You Be a Disc Jockey and “Now We Know” (Songs to Learn By). The images often had this realistic-yet-staged quality. Of course, album covers are designed for attracting attention and selling records, and the lines between art and commerce often blur.

We could see that instructional and self-improvement album covers altered the typical dynamics of cover design. They used familiar elements such as font or lettering and other visual expressions to create the appropriate feeling, but these covers looked different from, say, the Midcentury dance records. Geared toward the practical, instructional records stress function over form and often eschew artistic touches. The utilitarian—dare we say, managerial—vision often shifts instructional album covers’ graphic design to monochrome. Rather than embrace the full-color covers of records geared toward entertainment and evocative fantasy, instructional records generally hew to the no-nonsense, scientific, truth-evoking, black-and-white facts.

We drew on historian Michael Schudson’s idea of “capitalist realism,” which compared U.S. advertising to Soviet-era art that functioned as state propaganda supporting the Communist system. From this perspective, advertising imagery emphasizes the positive, obscures class differences, and assumes progress. But Schudson didn’t really articulate how it translated into design. Our sense is that designed-for-success record albums visually embrace the gray tones of determination and grit required to succeed in the competitive environment of the Midcentury American Dream.

You’ve written on the joining of cutting-edge design with marketing and promotional concerns that emerged as New Typography in Europe well before the 1950s. And Midcentury record albums are nothing if not manifestations of U.S. advertising pioneer Earnest Calkins’ notion of “atmosphere” that you drew out in observations on “commercial Modernism.”

Many elements of commercial Modernism resonate with instructional albums. There is this attempt to picture an attractive ideal grounded in the achievable everyday consumer life of postwar America. In 1973, Museum of Modern Art curator John Szarkowski was marking boundaries between art photography and the “commercial illustrations” of Midcentury photographer Paul Outerbridge. More recently, in 1988, Robert Sobieszek curated an exhibit in Rochester that examined advertising photography’s cultural relevance, and role of marketer and artist seemed less opposed. Sobieszek included work of Outerbridge and other Midcentury photographers such as Ralph Bartholomew, Victor Keppler and Nickolas Muray.

We recognized the influence of advertising innovations and corporate communication on our midcentury record covers and noted this in our book Designed for Hi-Fi Living. We were struck, for instance, by the visual resonance between photographs like Muray’s “Bathing Pool Scene” from 1931 and Kepler’s “Housewife in Kitchen” (1939) and Columbia Records’ Music for Gracious Living series, especially the album covers for Buffet and After the Dance.

In Designed for Dancing, we also discussed similarities between the album covers and representations of dancing in painting and photography. But we hadn’t included in the books the advertising images or paintings that we mentioned.

In Designed for Success, we rallied our courage to request permissions from museums and galleries for a few key photographs. We wanted our readers to see the visual commonalities for themselves. Muray’s early 1950s super-saturated red Hunt’s tomato catsup bottle hovering over vibrant orange cheese slices and green dill pickle reminded us of food and drink pictured on the covers of Adolph’s Music to Barbecue By and Music Minus One’s The Art of Mixing Drinks and Music. So, the catsup bottle photo appears in our book, as does Outerbridge’s 1937 photograph Food Display.

Could you wrap up with a few graphic standouts from Designed for Success?

Jason Kirby’s work on Guide to Jazz, where tiny trumpets, drums, directional arrows and other symbols create a computer punch card–like code for musical inputs and outputs that adorn the cover. Kirby’s striking irregular black, white, orange and fuchsia rectangles against a turquoise background found a home on many LPs: the same Modernist grid graphics appear on releases such as Duke Ellington and His Orchestra’s In a Mellowtone (1956), Tito Puente’s Top Percussion (1958), and The Mauna Loa Islanders’ Music of the Islands (1959). Kirby designed album covers for RCA and Columbia, as well as book covers and textiles.

Birth of a Salesman was produced for the Businessman’s Record Club, modeled after the successful Book-of-the-Month club. Birth of a Salesman’s cover design is credited to Don May, who worked for Chicago design firm Hoskinson, Rohloff and Associates. Against a big city nightscape, a lone salesman, with briefcase in one hand and overcoat in the other, walks an animated path, as dotted lines mark his sales territory as they indicate his movement within it. His graphic, clip art–like form allows him to stand in for every sales(man), his uniform of suit, hat and tie just visible as details as he strides on to the next customer. An unadorned sans serif font spells out the album title, “Sales” emphasized in white, and slightly misaligned with “Man.” Aptly, the cover art resembles a poster for a play or Broadway show.