Robert Andrew Parker lived a long, productive life, much of it in Canaan, CT, beside the Housatonic River. I used to visit his book-lined home often but regrettably lost touch about 20 years ago. Right after Christmas, when I heard of his passing at 96, I was reminded of a large watercolor he gave me—it was a green parrot—which for many years hung in my house that is only about 20 minutes away from his. It was taken down during renovations and has been sitting in the attic for many years. Looking at it again reminded me what a serene soul Bob was and how enticing and soulful his work was, whether he was picturing nature or war. He lived in nature in an old riverside property, close to the town’s famous covered bridge, and his house was filled with antique soldiers and tanks—the stuff he enjoyed drawing in incongruous recreations of war scenes.

In the mid-’50s, Robert Weaver, Cliff Condak, Alan Cober, Tom Allen and Bob Parker were at the crest of a new wave of representational American illustration. Of course, this is a subjective list, many more names can be added. But this was a group with varied styles, mannerisms and interests, and all brought an expressionistic intensity and impressionistic fluidity to editorial illustration. Parker’s work was arguably the most lyrical of the group; I always sensed he was making his art while in a trance. Hence, the parrot (which I will donate to the Norman Rockwell Museum this spring) is not just a bird but Parker’s vision of inner peace.

By way of remembrance, the following essay is a slightly edited form that I published as a precis to a Graphis magazine portfolio of Parker’s work in 1983. (Video by A’Dora Phillips and Brian Schumacher/American Macular Degeneration Project.)

He had no intention of becoming an illustrator, but Robert Andrew Parker is today one of America’s most influential. In the early ’50s, when he inadvertently entered the field, his unique blend of Impressionism and Expressionism—a marriage of fluid line and color—was anomalous, particularly compared to the mannered realism and literal sensibility of the postwar period. Parker’s idiosyncratic watercolors and etchings—in terms of content, a convergence of literary allusions and imaginary situations—were apparently better suited to experimental art galleries than to editorial illustration. Yet three important magazine art directors—Cipe Pineles, Leo Lionni and Robert Benton—who independently of each other saw his exhibitions, commissioned and published his editorial work, causing a snowball effect in popularity that provided him with a loyal following. In the wake of Parker‘s significant breakthroughs, other illustrators began to move toward simplicity and modernism.

If Parker’s work has the look of a child’s energetic scribbling, it is because he began drawing at the age of 10, and admits he never changed his style. Creating pictures of soldiers and battles was a way to entertain himself while enduring a drawn-out bout with tuberculosis, isolated from the rest of the world in the New Mexico hinterlands. Ironically, upon regaining his health he stopped drawing, as if art was a curative for which he had no more need. Instead, Parker turned his interest to books: “I devoured every wildly unsuitable volume in the schoolhouse,” he recalls, “from The Mysterious Stranger to King Solomon’s Mines.” Music was his second passion. He played clarinet and saxophone in small combos. And, had he not thought that it was impossible to be as good as his musical idols, he would never have returned to the visual arts.

In 1948, after Army service, Parker entered the Chicago Institute of Art on the GI Bill. He studied painting and print-making, and was inspired by the work of the famed Stieglitz group of the 1920s, Arthur Dove and particularly Charles Demuth, whose watercolor style he emulated. Moreover, Max Beckmann’s emotionally charged prints and Otto Dix’s horrific World War I etchings made a lasting impression. His classmates were Claes Oldenburg, Robert Indiana and Leon Golub, and were all influenced by the teachings of R.O. Taylor—an obsessionist whose own fixations with cultural ephemera were central to the emerging Pop Art movement. Parker later fine-tuned his printmaking skills at the prestigious Atelier 17 in New York City. Next, a job on the set of the film A Lust For Life rendering facsimile Van Gogh paintings [for the star Kirk Douglas to use as props] filled his pockets with coin and his head with knowledge.

Although Parker came of age during the Abstract Expressionism era, he shunned it, choosing instead to capture narrative form in impressions of variegated internal and external stimuli, including his dreams, monkeys and apes, Marat/Sade, Thelonious Monk, and images of war. It all somehow served as fuel for numerous expressive, often witty images. “I always courted ideas,” he says, “in the hope that I would find something that would hit me, in which I could totally involve myself.” This courtship has taken him all over the globe, including a climb up the Himalayas and treks across Africa, resulting in journals filled with sketches for future projects.

He creates a prodigious number of images on specific themes in as many different media as possible. “I have an embarrassing amount of paper at the end of the year,” he says. Once, during the Vietnam War, he visited his town’s garbage dump and found a surgeon’s operation manual with terrifying graphic examples that became the source of a year’s worth of powerful antiwar imagery.

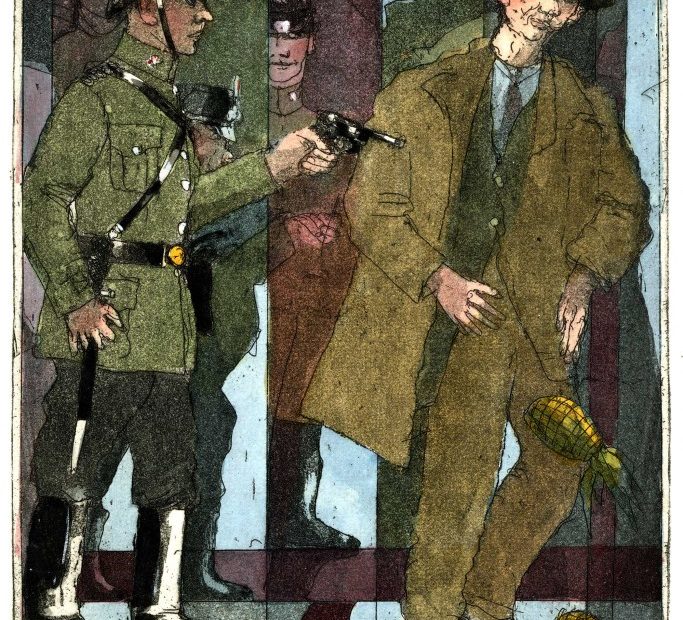

Parker practices a deceptive form of Expressionism. “My work is not Expressionist in the usual, Germanic manner,” he says. “My primary colors are Naples yellow and shrimp pink.” But when he has a message to impart, it is definitely articulated. His most well-known series, “The Imaginary War,” published in Esquire, was as much an antiwar statement as it was a series of boyhood fantasies. A similar cycle of narrative protest images, “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner,” is so counterintuitively calming to look at—almost naïve in its simplicity—with the inevitable death scene at the end of the story so surprising that it is more powerful than many overt depictions of warfare. Parker’s subtle approach to picture-making and its youthful energy make his art so enticing.