Steve Brodner is the next generation. It took him some time to get there, but now he is old enough to be cynical, young enough to not let that weigh him down, and just ripe enough to make innovative commentary. He knows that even the most acerbic satire and rude ridicule will never defeat the continually replenished trough of minor demigods and neo-oligarchs.

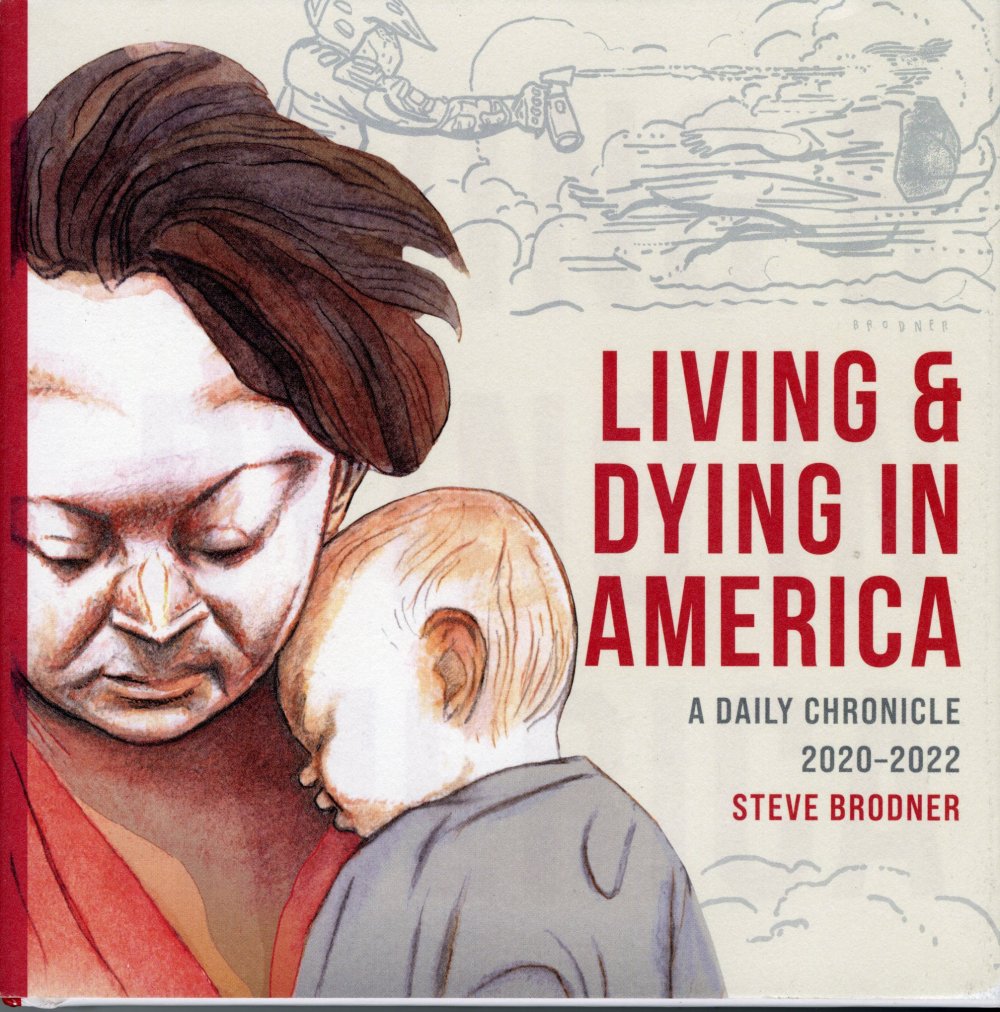

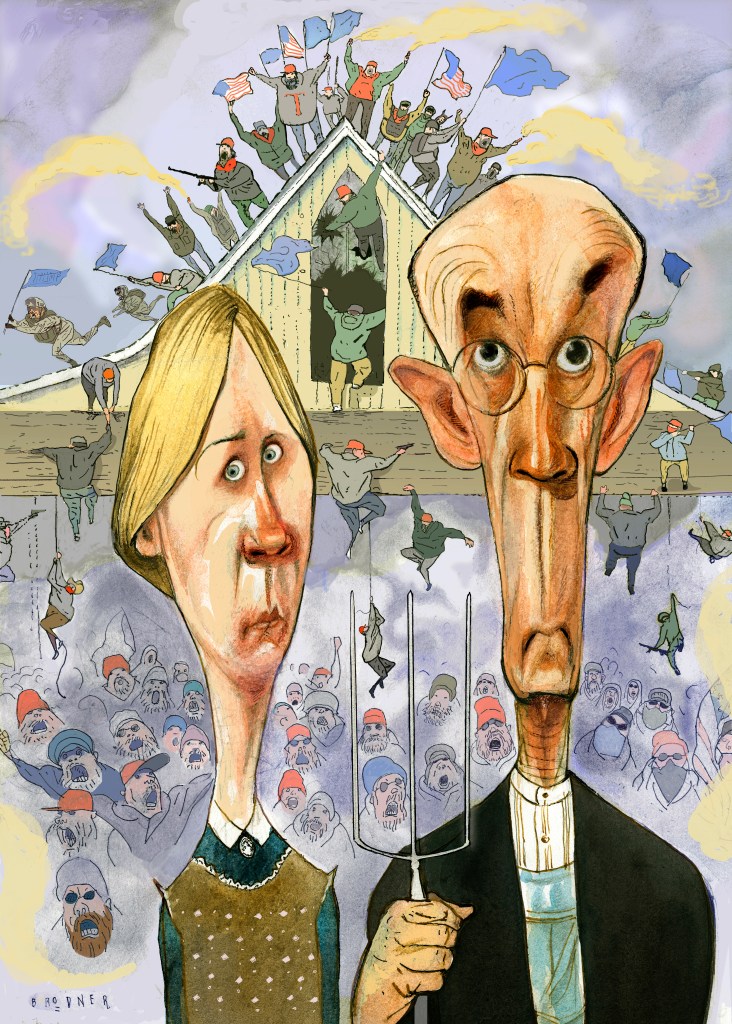

Brodner’s new book, Living & Dying in America: A Daily Chronicle 2020–2022 (Fantagraphics), continues a heritage of the artist as witness—yet it transcends that heritage by combining the truth of contemporary ideas with the idealism of contemporary thought. I asked Brodner to talk about this unique 476-page historical record of what the ongoing pandemic wrought, and how the brave fought, the cowardly retreated and the venal profited.

Tell me why you decided to make this chronicle of the American experience. Was it a response to COVID isolation?

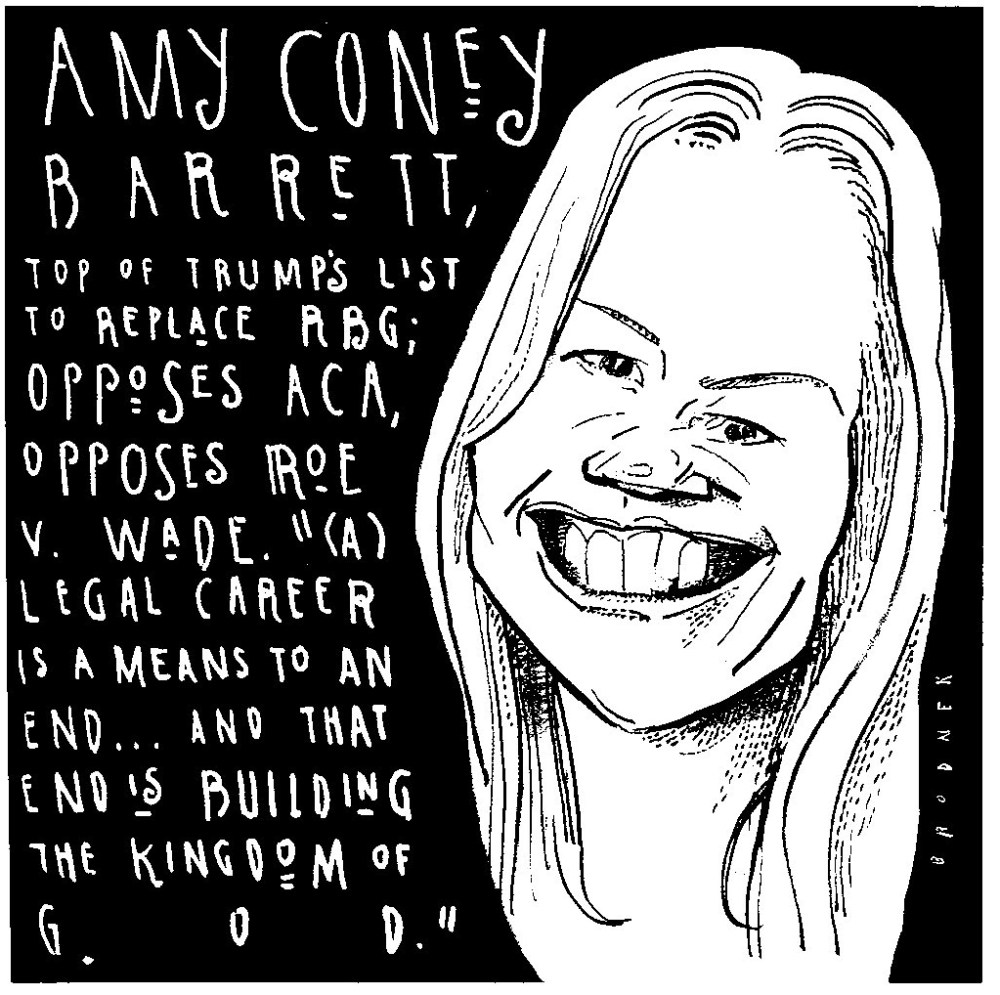

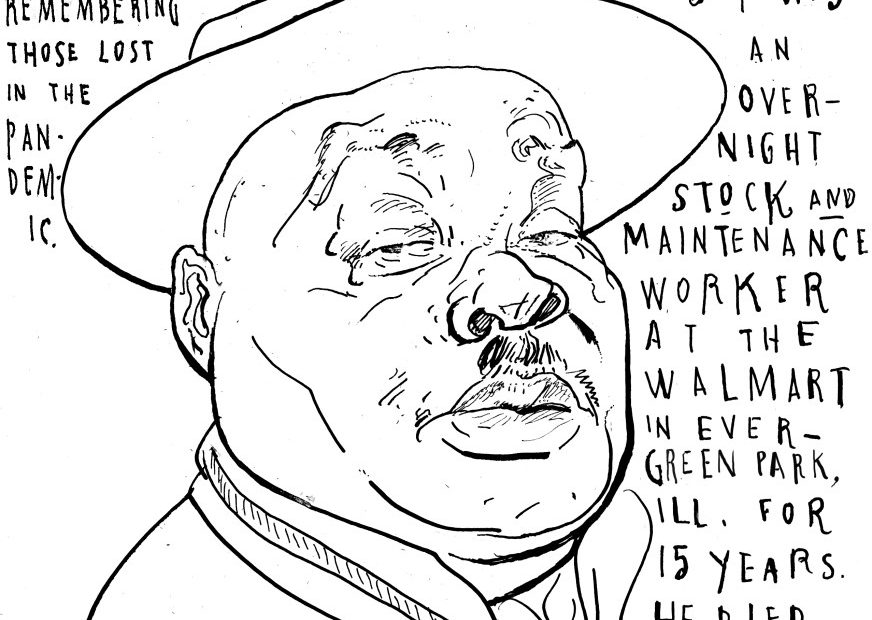

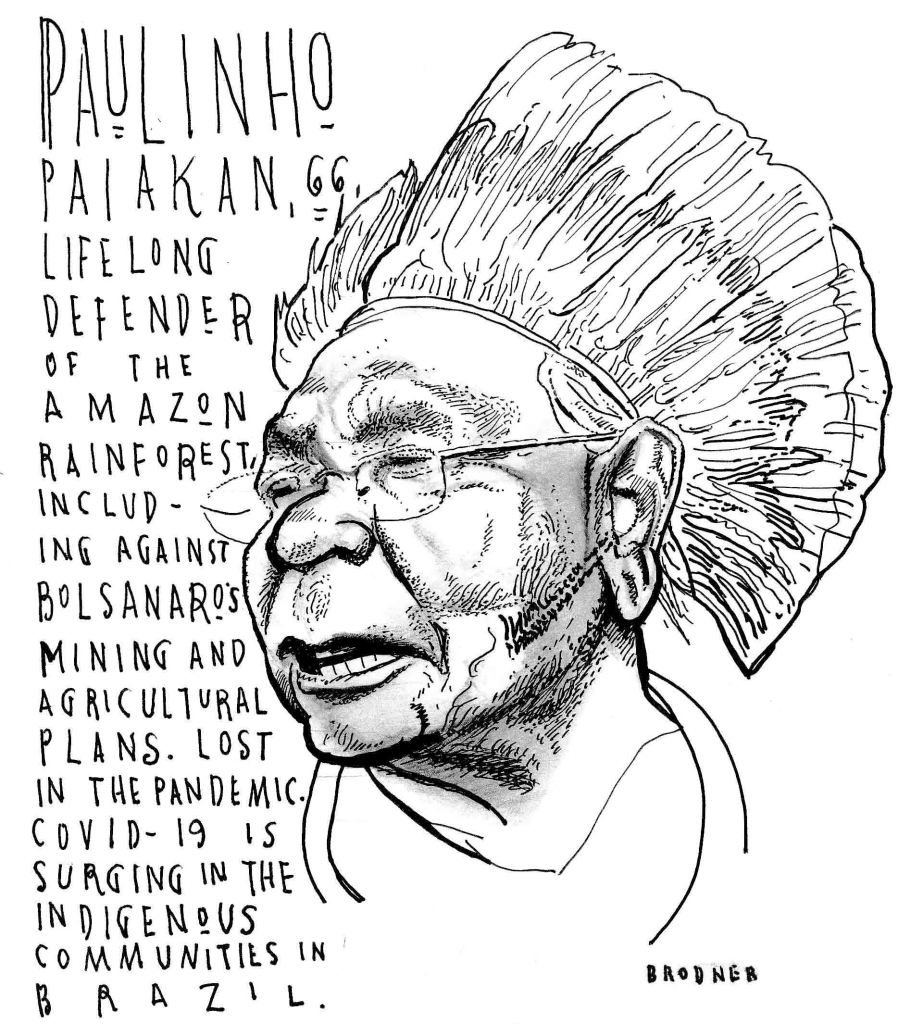

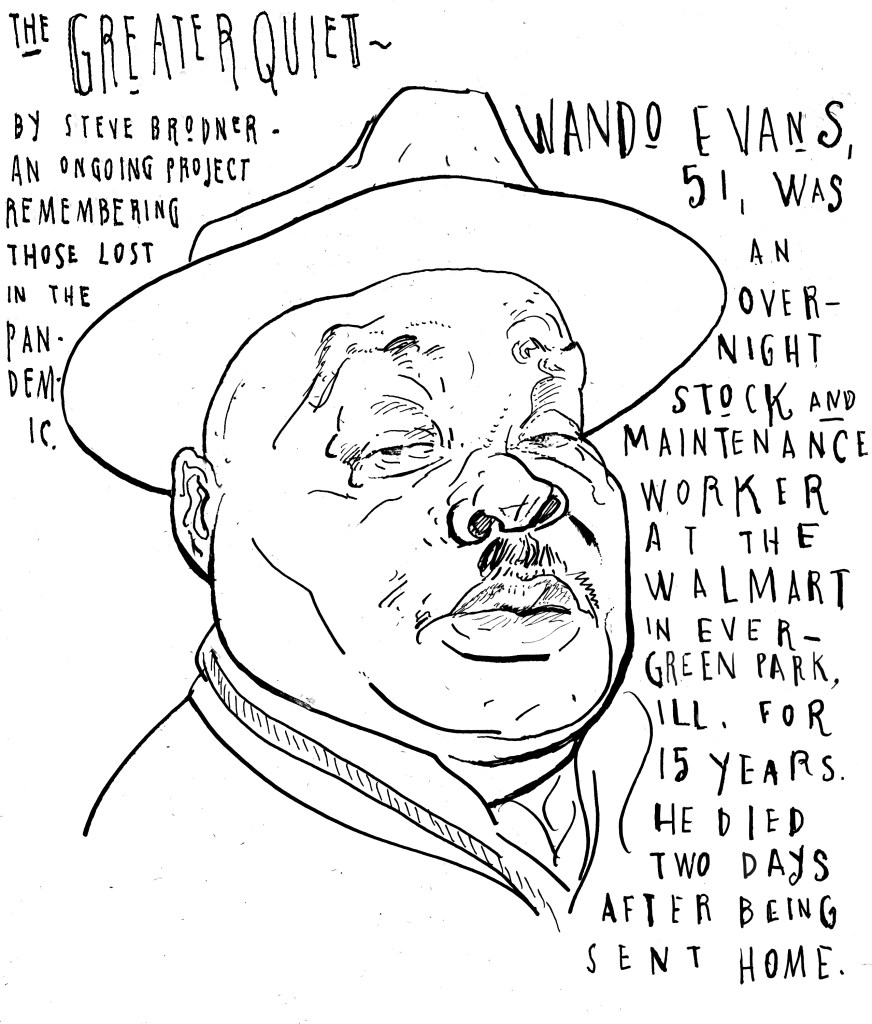

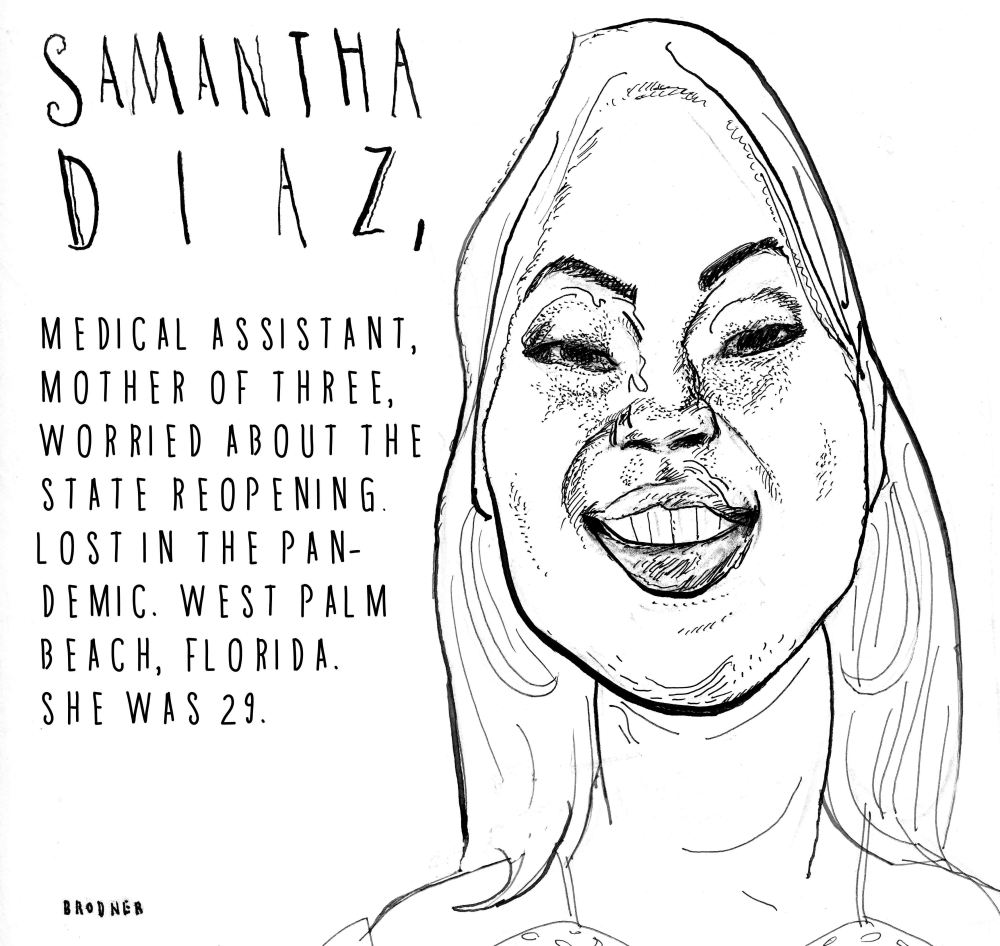

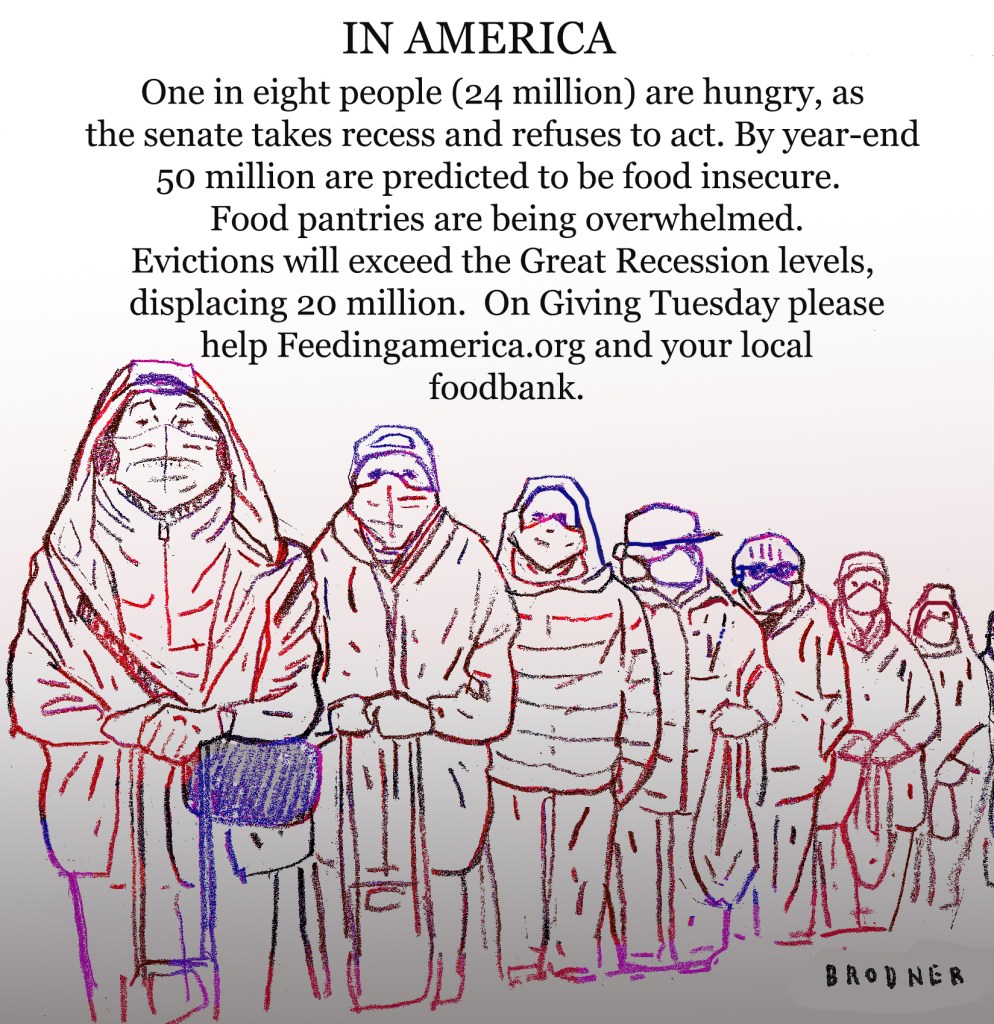

Very much. It was a strong reaction to the powerlessness one felt at the onrush of unrelentingly sad news about the pandemic. It started with a story about Kious Kelly, a young nurse in New York who gave up his life to save his patients. I wanted to stop and consider each life for a few minutes. This was a way to do that: to see their faces, tell their stories, hear their voices. Soon there were musicians, politicians, frontline workers, people in meat-packing, criminal justice, schools, grocery stores, nursing homes. And politicians lying about it. It started on social media, then became a regular feature in The Nation, where you can still see the week’s work collected every Friday by Robert Best (and daily here, where you can subscribe for free).

You have many themes running through, most all of them linked to an individual—good and bad people. What was the reason for their selection?

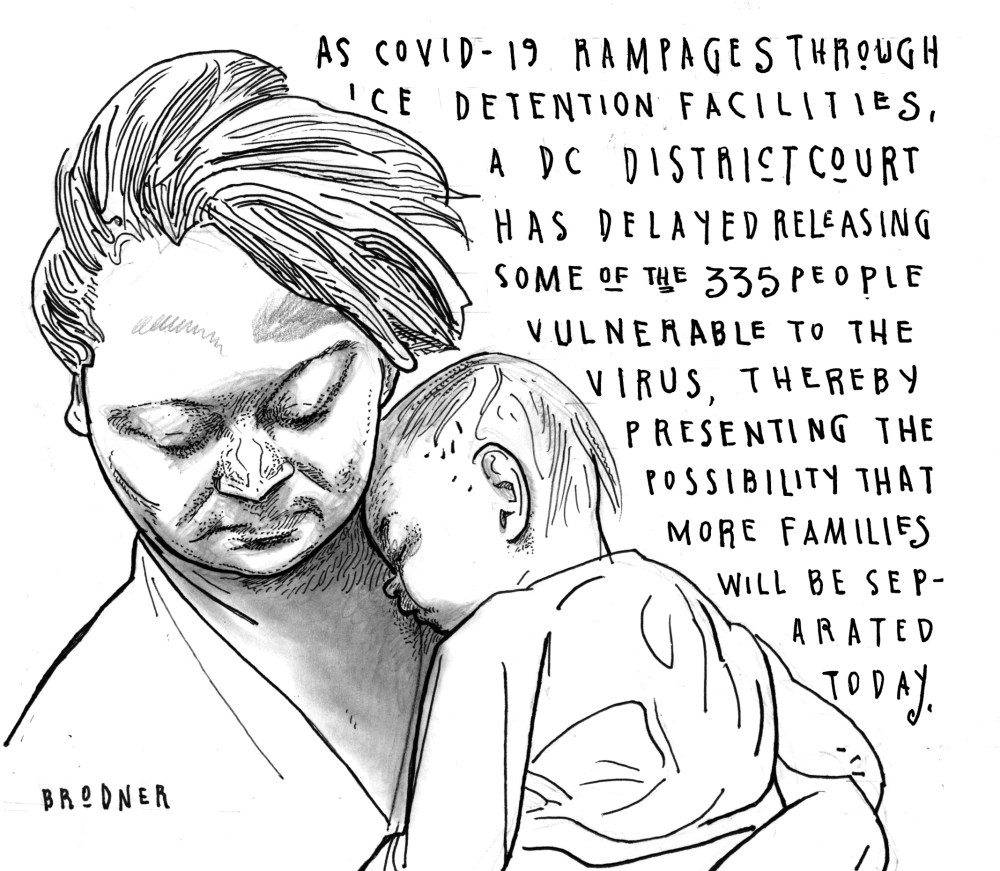

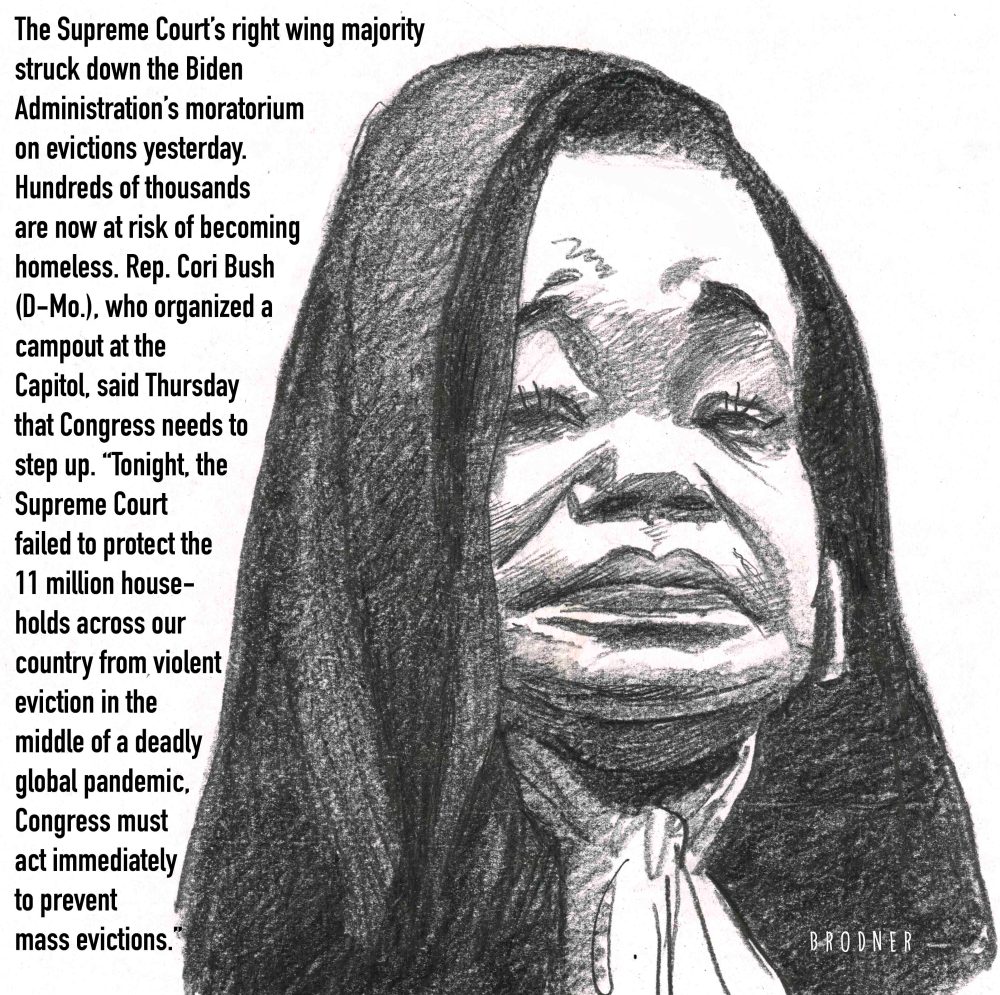

At first I wanted to tell the story of the toll the pandemic was taking—to hold each story up to the light for an extra moment. Then it moved to stories of racial justice, climate, then the election, the campaign against democracy and the insurrection, etc.

Each night I asked (and still ask) myself: What is the story in the news today that has the strongest emotional pull? Each page in the book tracks a visceral reaction (often sadness or anger) to an injustice that connects powerfully enough in that hour to call out for a new page.

What excites me about your work in this book is the variety of simplicity and complexity. Each addresses an emotional high or low. What governed your choice of approach?

I found, as I went, a great stylistic freedom as I had never felt permitted to have as an illustrator. In this series there was no art director, editor, publisher. I could then be free to only care about what each image was saying, and let the “medium be the massage.” In many cases I just give the piece what it needs. (In some cases I give it all I can spend. Some of these were done in one hour, late at night, when I could hardly see straight!)

Why did you decide to use the incarcerated woman and child as the cover? How does it sum up the project?

She seemed to say something about the project to me. She is strong, loving and taking the brunt of the crisis. A pandemic, as you know, like a war or depression, punishes people already most burdened in society.

Your caricature (e.g., the Treason Caucus) and portraiture (e.g., parents of 435 migrant children) complement each other nicely. What triggers caricature over portraiture and vice versa?

The portraiture here is a departure for me. As you know, I have been a caricaturist for about 50 years and have not had the need, aside from art journalism, of which I have done a fair amount, to draw with empathy. There were always too many hypocrites to attack! Here I needed to show how I felt about these people. I feel very lucky to have been able to communicate these feelings in a non-satiric way. Satire, parody, caricature were definitely called for during those two years and I have certainly enlisted those grotesque creatures where necessary!

One of the claims of this book is that you are “the visual chronicler of our times.” Would you agree with that assessment?

Never! I am a drawer who does a new picture every day. Some days it is not good. Then there are days it is pretty good. Sometimes (not frequently enough) it’s good. Joe Ciardiello, one of the finest illustrators and draughtsmen in the world, gave me this quote. And if he says it, it gives me hope that my batting average is improving.

This book highlights your conscience and humanism. What, if anything, would you say could have been further accomplished?

What is left is what you do today and tomorrow. And these things are informed by what you learn from yesterday, combined with new information coming in tonight. It’s all pretty much out of my hands.

What do you want the audience to take away?

That would be up to them. When I saw the collection for the first time, I took away the intensity of those times. I remembered the sirens in the night, the pots and pans and whistles at 7 p.m., the news of precious people being lost, the mendacity of Trump and the Niagaras of misinformation and disinformation, adding to the megadeath. And then the killing of George Floyd. Remembering our times with vivid intensity can only help us center ourselves and help us with, God save us, whatever is coming next.