Modernity is a slippery slope. It defines society and culture in many ways, through art, commerce and technology. The Nazis were ideologically opposed to modern art as an affront to the Germanic ethos, but took their own contemporary spin on business.

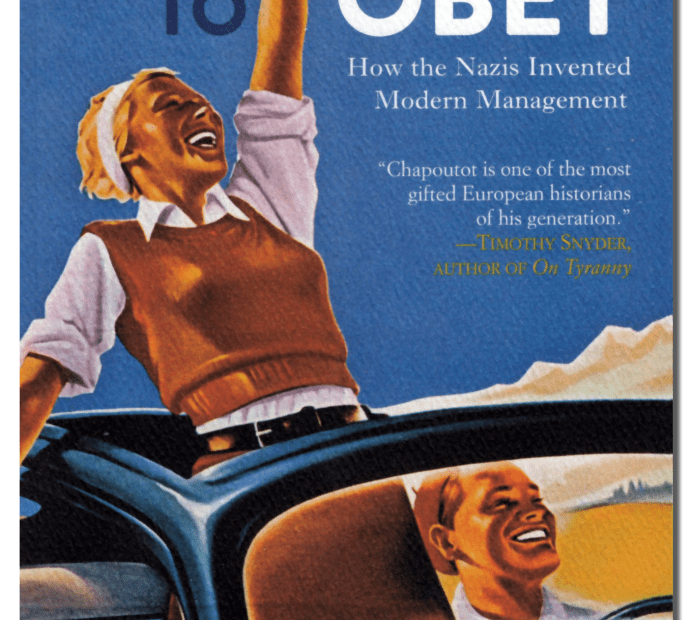

By accident, while browsing the tables at P&T Knitwear Book Shop in New York, I happened upon a concise yet extraordinary history of the Third Reich by Johann Chapoutot, Free to Obey: How the Nazis Invented Modern Management. The focus is on how Nazi theories about the organization of labor and leadership (Menschenührung, or management) were key to rejecting “the traditional state” in favor of modern semi-autonomous “agencies” not controlled by government but existing as a “movement” at the behest of the leader (führer).

Chapoutot sheds light on the ideology that “the absolute horror of the Nazis’ crimes was perhaps less archaic than contemporary: a certain economic and social organization, and an impressive mastery of logistics, made possible, or even promoted, a series of crimes that were casually attributed to the most backward barbarism rather than to the disciplined structure of a resolutely modern enterprise.” Focusing on social scientists who were fervent Nazis (eugenicists to the core), Chapoutot explains how modern corporate management, which underscores American and global capitalism (and to a great extent the current Trump/Musk government dismemberment), was conceived.

The protagonist of this history is Reinhard Höhn, a lawyer, high-ranking SS official and one of many organizational specialists who believed that Nazi racial policies were reconciled with nation, tribe and nature, all geared toward creating a National Socialist community (Volksgemeinschaft). The regime was open to a managed life. According to Nazi theorists, a society bound by class conflicts was an aberration due to French revolutionaries, Karl Marx and Judeo-Bolsheviks. Nazis promised a contemporaneously organized society of “race comrades” united in a battle that Germany “had to wage to survive.”

As Chapoutot recaps the outlook, “Life is a constant battle against nature, against sickness, against other peoples and other races.” It was a Social Darwinist principle, radicalized by the Nazis in response to Germany’s “rapid and brutal modernization,” notably during and after World War I.

For the Nazis, the “Germanic man was the man of the ‘community’ (Gemeinschaft) and ‘work’ (Arbeit) and interested in efficient production of consumables.” The Germans were the largest producer of methamphetamines to increase the productive potential of its soldiers and workers. Höhn was a proponent of maximum managerial success by applying the concept of human resources (yes, Germany is where the HR profession was fine-tuned). When the Nazis unconditionally surrendered in 1945, managerial experts of Hölm’s stature in the SS did not simply disappear. He shed his uniform to become manager of the German future, a proponent of “German freedom”—the flexibility and elasticity of its agencies integrated into the Federal Republic of Germany (West Germany) and the economic miracle therein. He gave up “the rabid racism of the 1930s, anti-Semitism, and the quest for Lebensraum” (living space), but did not renounce certain fundamental ideals of his Nazi past. “As he saw it, the Third Reich doubtless failed because it was not Nazi enough,” and had not put into practice his (and others’) concepts of management.

Free to Obey is at once a fascinating story about a devotee of what is considered today successful business management, and a terrible revelation that Germany’s technocratic future was being designed by many of its World War II actors.

The post The Daily Heller: The Dirty Secret of Modern Management appeared first on PRINT Magazine.