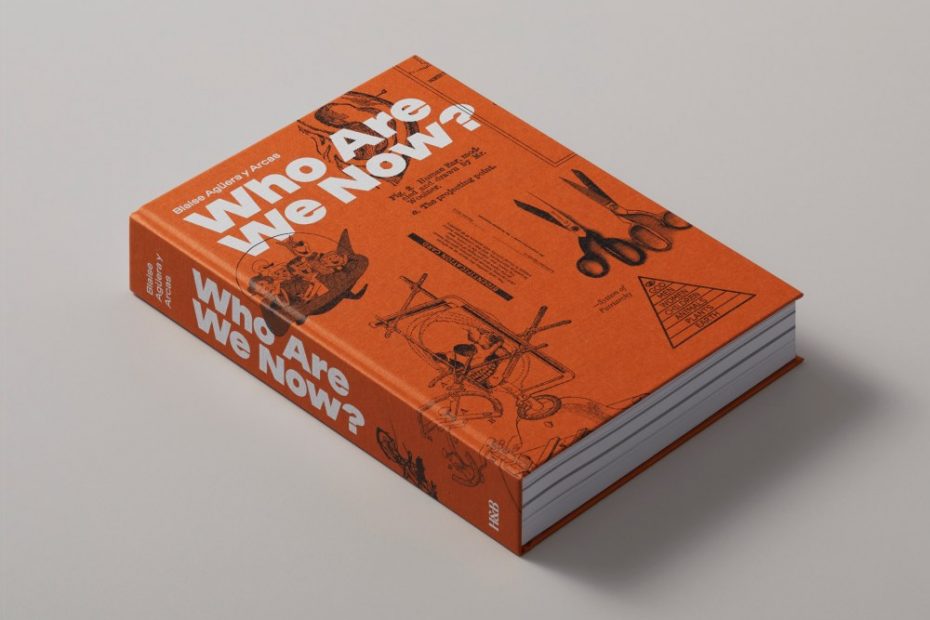

Google AI researcher Blaise Agüera y Arcas is the author of Who Are We Now?, a timely investigation that recasts how we perceive human identity—specifically gender and sexuality in America. Designed with iconic and quotidian imagery, charts and data visualizations, it is an intriguing mirror to American culture, driven by irrefutable fact rather than fungible ideology.

At its heart, Who Are We Now? is a set of surveys Agüera y Arcas conducted between 2016 and 2021, asking thousands of anonymous respondents questions about their social behavior and personal identity. The resulting window into people’s lives is akin to the famous Kinsey Reports, which quantified as it scandalized postwar America more than 70 years ago.

Today definitions of heterosexual “normalcy” is on the wane, and Agüera y Arcas observes that the landscape today is—”in every sense”—even queerer. After ages of being biblically and practically fruitful and multiplying, we’ve strained our planetary limits. Domesticated animals far outweigh wildlife, and many species are in catastrophic decline. Human fertility is now stemmed by choice rather than by premature death.

On the heels of Agüera y Arcas acclaimed 2022 novella, Ubi Sunt, a winner of AIGA’s 50 Books | 50 Covers Award, Who Are We Now? sets the stage for what he calls Humanity 2.0, exploring how biology, ecology, sexuality, history and culture “have intertwined to create a dynamic us that can neither be called natural or artificial—but rather an existence between existences.”

This is a profoundly visual document in analog and digital formats designed by New Zealand-based James Goggin, and published in the United States by Hat & Beard Editions. Prior to publication, Agüera y Arcas shared his motivations for authoring this psychological and philosophical wellspring of existential ideas that are defining our current paradigm shifts.

This book asks some very important questions about how we will live our collective and individual lives over the next 20 or so years. What prompted you to tackle such an existential project?

In 2016, when I began running the surveys that provided a lot of the data presented in Who Are We Now?, one of my concerns was fairness and bias in AI systems. (Although AI isn’t the book’s main topic, some findings from that period do turn up—for instance, in Chapter 14, why AI-powered gaydar doesn’t work.)

A core question was: How do AI models behave differently for different groups of people? Studying fairness rigorously required understanding how people think about their individual and collective identities, and that motivated some of the first surveys I ran. Identity was also playing an increasingly dramatic role in politics over that time, and learning how it interacted with beliefs and behaviors was also a motivation.

As I got deeper into this work, though, my reasons for doing it evolved. I began learning surprising things (to me, at least) about human identity, and wanted to share those insights in a way that did them justice. It was a deep rabbit hole. To be honest, I would probably never have begun the project if I’d known how deep, and how many years it would take to complete.

But also, between 2016 and 2023, the world changed. AI advanced tremendously, of course, and in the responses to it, I see a mixture of our very human tendencies: on one hand, the drive toward cooperation and symbiosis, the sense of great collective opportunities. On the other hand, fear and rejection of the “other.” These are the same very human tendencies that are driving the culture wars.

You have quite an extensive litany of questions and answers. Have you covered all or just some of the trigger points of the early 21st century?

It is indeed a long list of questions, but nowhere near long enough to be exhaustive. People are infinitely complicated; their identities and concerns are like a fractal, with ever more detail as you zoom in. However, one of my overall findings was that many answers correlate. That means that, while not everything can be covered, certain big, overall patterns are obvious, even if not every question was asked.

A caveat, though: Race is a big topic that I only address in a few places in the book, and far more superficially than sex and gender. The main reason is that while my survey data is from the U.S., I attempted to focus on more global patterns. Each country defines race in its own way, and has its own tangled history; the American story is especially knotty. So no, I certainly didn’t cover all of the trigger points!

In the promotion for the book this is called Humanity 2.0, exploring how biology, ecology, sexuality, history and culture have intertwined to create a dynamic “us” that can neither be called natural or artificial. Hasn’t this exploration been examined continually throughout history?

Sure—every generation believes it is “modern,” and perennially asks how artificial or “unnatural” the lifestyles of the young are relative to previous generations. As one survey respondent put it, “We were once the younger generation and some of us were wild and crazy, but not all. In so many ways the different generations are more alike than people want to believe.”

Still, I’m inclined to defend my claim. The world is now culturally and economically integrated in a way that it wasn’t when I was a kid—and never had been. The internet has become a kind of planetary nervous system. All of the world’s cities have become nodes in a realtime network. And at the same time, global warming confronts us with a truly planetary emergency; we haven’t experienced anything like that over the past 10,000 years, the entire span of recognizably human culture. We’ll also begin to decline in numbers this century, which is equally unprecedented. To crib the title of an old sci-fi novel, we are, as a species, at childhood’s end.

Doesn’t custom, intellect and knowledge change our mass behavior on a regular basis? Where does what we were and who we are combine to make who we’ll be?

Humans are cultural to an extraordinary degree. Unlike nearly every other animal, most of our behaviors are learned, and our knowledge accumulates over generations. That is both the secret of our success and the reason we are unstable, exponential, unsustainable.

My hope is that our culturally accumulated intelligence will allow us to think our way through the coming century. It certainly seems possible, but our continued success is by no means a foregone conclusion. In the past, there were many competing human tribes, countries or other polities, all with different ideas; they rose and fell, sometimes competing and sometimes cooperating. Our eggs were not all in one basket, as they are now. We have—or are—one planet.

Who Are We Now? incisively confronts how societies today perceive human identity, specifically gender and sexuality “driven by irrefutable data rather than ideology.” Where does the data come from? And how do we separate ideology (or belief) from the equation?

Of course the data still needed to be interpreted, and interpretations should always be subject to scrutiny. That’s why there are so many graphs in the book. I show the data, rather than just citing percentages. In the online edition, the graphs can be further customized, and the anonymized data downloaded for further study. So while I don’t think any analysis of social data can truly be a “view from nowhere,” I do my best to put my own cards on the table, and leave the door open to alternative interpretations.

In addition to the data visualizations, you’ve filled your book with dozens of visual pop-culture examples. How much input did you have in the selection of images to tell your story?

Dozens? More like hundreds! The design of the book was a deep collaboration with James Goggin, a brilliant book designer based in New Zealand, along with web designers Marie Otsuka and Minkyoung Kim, plus frequent input from my longtime research assistant, Johan Michalove. In general, I picked the images, but we often discussed and debated them, and sometimes needed to find alternatives. Then, we sweated the details of the layout. The four of us met weekly for over a year.

I am very interested in your take on the pronoun wars. I’m probably a hold-out for the binary solution of life. Why am I wrong … or can I be partly right?

Well … one of the book’s points is that there is no absolute wrong or right; words are culturally defined categories. That doesn’t mean that they don’t correlate with objective evidence—and gender does correlate with sex characteristics, which are approximately binary. However, as shown in the book, the correlation is not exact, and neither is sex exactly binary, no matter how you define it. These are both facts, not opinions—by which I mean that saying otherwise would be in conflict with the data.

Of course, it is also a fact that some people disagree with others about language and definitions. We should celebrate that! Without such variability, language could not evolve, and language must always be evolving to suit our changing needs.

Speaking personally now, though, I will add that if someone asks me to refer to them in a particular way, I will do my utmost to honor their wishes. That just seems to me like basic decency. In the book and in my life, I try to adjust my mental models to fit the evidence, rather than assuming that my preconceptions are right and the evidence is wrong. And when the subjects are human beings, what they have to say about themselves really is the relevant evidence, in my opinion.

What have you learned from Who Are We Now? that is a surprise or revelation?

There were quite a few surprises for me. Here are a couple. Intersexuality—meaning a mixture of male and female sex traits—is a lot more common than most of us realize. It has usually been thought of as a private medical condition rather than a public identity, which is why it remains so obscure. This has some interesting implications, which the book explores, but at bottom, I wish it were more widely understood and normalized, as I think that would also go a long way toward removing its stigma.

Another surprise was the dominating role of population density in determining people’s beliefs, politics and identities. It’s common knowledge that the countryside is more conservative than the city, but really seeing the data on this, exploring the reasons why, and unpacking the implications kind of took my breath away.

From the data you’ve collected, can you predict the future or see the present more clearly?

Supposedly it was Yogi Berra who said, “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” Whoever came up with that, I really like it! There are some sensible approaches to prediction, though. One comes by way of another famous observation, this one from cyberpunk author William Gibson: “the future is already here—it’s just not very evenly distributed.” In particular, when we notice that cultural evolution happens faster when people gather at higher densities, we know where to look for the future: in cities.

Another helpful observation is that while certain variables are inherently unpredictable—like the weather—others have inertia, and are subject to predictable long-term trends, like the climate. We know that global warming is real, and similarly, there are demographic, land use and technological trends that tell a clear story about the coming century. Those are explored in Part III of the book.

As for the specifics of identity politics … that might be more like the weather, though we can safely expect that many young people will continue to check the “it’s complicated” box.