Racial stereotypes were ubiquitous throughout commerce and art during late 19th- and early 20th-century America. In particular, those drawn to the music biz in New York City, known as Tin Pan Alley, were frequently and insultingly stereotyped in pre–World War I America. Just take a look at the ephemera produced, collected and currently on view in the exhibit Illustrating Tin Pan Alley: From Ragtime to Jazz at the Society of Illustrators New York until Oct. 12. The collection belongs to Harlem historian John T. Reddick, whose research has focused on that community’s Black and Jewish music culture between 1890–1930. Here he speaks about motivations, discoveries and outcomes of this visually charged show.

John, how did you get started collecting the sheet music art and illustration of Tin Pan Alley?

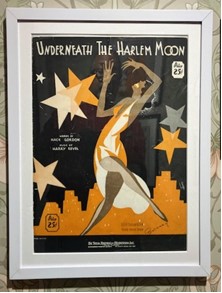

In truth, the first items I collected were out of a desire to find unique and interesting graphic images of African Americans and Harlem cultural life as decorative art for my apartment. Two items from that early period are in the exhibition, Al Frueh’s 1922 caricature print of the Black theater performer Bert Williams, and Sydney Leff’s sheet music cover for “Underneath the Harlem Moon,” 1932.

What was the importance of Tin Pan Alley to American music and culture?

Tin Pan Alley has remained the tag name for the collective nucleus of composers, performing artists and music publishers who, in coming together, have served as the generators and disseminators of American theatrical and popular music. In the early days that alliance served to standardize, distribute and promote performing artists and composers, expanding the audience and reach of their work. Music publishers, for example, worked in tandem with mainstream newspaper publishers, providing sheet music of popular songs as supplements to their papers. This method of distribution served to circulate musical compositions and their associated performers more broadly to the broader public. “Der’ll be Wahm Coons a Prancin’,”1899, and “Bully Song,” are two such examples offered in the exhibition.

Why was Tin Pan Alley located on West 28th Street in New York City (just around the corner from where I live today)? What was happening in the area when it was there?

The theater district in the late 19th century had begun to move north of 14th Street, settling in the area of Broadway north of the Flatiron Building and Madison Square. During this period stronger copyright protection laws came into effect as well, facilitating songwriters, composers, lyricists and publishers working together for their own mutual artistic and financial benefit. What had been residential buildings along 28th and 29th streets were converted at the street level to commercial use, with rooms on upper floors serving as offices and music studios.

I understand that the songs musicians were playing for music publishers music would waft out onto the street.

The composer and journalist Monroe Rosenfeld was already being profiled as a “leading writer of popular songs” when, while visiting 28th Street’s music publishing houses in the company of composer Harry Von Tizler, one of them noted that the din of competing piano playing sounded like a cacophony of banging “Tin Pans.” Rosenfeld, then employed as journalist for The New York Herald, popularized “Tin Pan Alley” as a descriptor for the city’s music publishing district. Rosenfeld’s elevated position in both these professions was often leveraged to his advantage, with artists and publishers eager to curry his favor. The popular team of Bert Williams and George Walker, the self-titled “Two Real Coons,” performed one of Rosenfeld’s compositions, “I Dont Care If Yo Nebber Comes Back,” which must have served toward advancing the team’s notoriety and commercial viability.

Were Black artists ever credited with the music that was published through Tin Pan Alley?

In the early days of music publishing, copyright infringement was a pervasive problem for all composing artists. Eubie Blake, the African American composer and stride-pianist, stated that publishers would pay Black composers a flat fee for a song, with no published composer credits or royalties. In those cases, if he thought the song would be popular, he’d sell it to several music publishers, figuring, let them fight it out if the song became a hit. In 1914 the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) was founded, and African Americans were among its charter members, which included the composers Will Marion Cook, H. T. Burleigh, Will Tyers and the brothers J. Rosamond and J. Weldon Johnson.

How were the artists found, trained and directed?

The artist Al Hirschfeld and Sydney Leff attended the Vocational High School for the Arts located on 138th Street in Harlem, which at the time was the city’s only school providing commercial art training. Later, they both took classes at the National Academy of Art as well. The vocational school required students in their junior and senior years to seek professional experience, which led Hirschfeld to finding initial employment in the art department of Goldwyn Pictures, and Leff illustration work in music publishing.

Where did the artists who created the sheet music covers come from? Did they have their studios on the street?

There are several New York–based illustrators’ work in the exhibition; prominent among them are the Starmer Brothers, Joseph Hirt and John Frew, who illustrated the cover “My Dahomian Queen.” Another illustrator, Morris Rosenbaum, was Harlem-based, signing his work Rosenbaum Studios or with an RS and rosebud logo, as in his cover for the Sophie Tucker novelty song.

The focus of your exhibition is on sheet music art (I too have a fair collection of the same). Much of the art is for what was known as “Negro Music.” Why were these tunes so popular, and why was “Negro Music” so widespread?

Aida Overton Walker, “The Queen of the Cakewalk,” was a dancer, choreographer and performing partner of George Walker. To her and other Black performers, the Cake-Walk was an old-fashioned dance when, suddenly, to her amazement, it became an international dance craze. Cultivated among African Americans, the steps drew on African dance traditions and a mimicry of white American’s European social dance styles. The show “In Dahomey,” in which the Walkers and the larger Williams & Walker Company performed, introduced the dance to Britain, including a performance at Buckingham Palace and in parts of Europe. It was the first global dance craze identified as American, 20 years before the jazz era’s Charleston dance fad.

I have copies of Yiddish sheet music, Indian melodies, and a smattering of Irish as well. Why were ethnic and racial references so common?

I’ve come to reference the logo of the Chas. B. Ward Music Publishing Co. (above) as my answer to this question. In the ethnic mix of New York, one was always “looking over the fence” at other cultures and communities. With all the barriers of language, religion and culture that existed then, there was clearly also an awareness and curiosity in others. For commercial entertainment to engage the broadest popular audience, its initial level of engagement would necessarily be simplistic and rudimentary. I’ve come to recognize elements of these early efforts as a bridge to broader possibilities, rather than overtly derogatory, as we might come to interpret those efforts today. The exhibition’s W.E.B. DuBois quote regarding “double consciousness” is a consciousness that I believe has an empathetic audience among more citizens than just African Americans—it resonates with anyone who finds themselves identified as an outsider to mainstream culture, yet by necessity must craft varied faces to navigate and survive.

Were the stereotypes shown on the sheet music covers truly popular with the public? Was it novelty, convention or what?

Reuben Ernest Crowdus, aka Ernest Hogan, was a prominent and highly regarded African American composer and performer of the ragtime era, and the popularity of his song “All Coons Look Alike to Me,” with its sheet music cover, grossed sales of over a million copies, serving to promote what became a defining “coon” illustration and persona among the broader public. Eventually, Black audiences and artists came to resent the stereotype, which later served to diminish Hogan’s status as an artist and performer.

The dominant titles, lyrics and imagery of early Tin Pan Alley music publishers retained a vested clinging to stereotypes of African Americans and an assumed intimate association with chicken, cotton and watermelon. A typical illustration is the sheet music cover “Cotton—A Southern Breakdown” by Joseph Hirt. Black composers and performers of the era often parodied the notion or tried, as best they could, to move beyond it.

Recordings were in their infancy, if at all. What was the role of sheet music in the professional and amateur worlds?

Sheet music was the first standardized mass-market disseminator of musical compositions and their associated lyrics. In that way they advanced not only a song’s distribution, but also its access to varied audiences and varying individual interpretations. The popular song “Darktown Strutters’ Ball” by the African American composer Shelton Brooks demonstrates a “triple consciousness,” as seen in the varied covers the publishers and illustrators craft as the salable identity for the song.

Later music recordings would not only expand a song’s exposure but add the need for other ways of conveying through marketing a performing artist’s racial identity and musical authority. W. C. Handy’s record company Black Swan Records, in its record artist catalogue, would state, “The only genuine colored record. Others are only passing for colored,” to distinguish between all the non–African American imitators.

What attracts you to Tin Pan Alley’s legacy today?

I was drawn into the New York City landmarking of Tin Pan Alley after being infuriated by the tactic of the local developer historian Andrew Alpern, who took to displaying on TV and in public hearings sheet music images that he stated “would shock current sensibilities.” He was choosing to distort history to his own ends, and with that reflecting a personal disinterest and lack of knowledge in African American musical history, that reflected our true struggles, successes and evolving partnerships with other artists toward creating a broader and more inclusive American songbook.

His examples used sheet music covers like “All Coons Look Alike to Me” and “Let It Alone,” performed by Bert Williams. Other illustrations much like these were compositions by African American composers, published by Gotham-Attucks, 28th Street’s Black publishers named for the New York metropolis and Crispus Attucks, an African American casualty in the Boston Massacre at the hands of the British, histories that were going unmentioned.

It was clear from this that my collection and research knowledge could help leverage support for landmarking Tin Pan Alley by providing a broader history of the African American presence and talent that passed through 28th Street and its music publishing houses. So, I joined a group of preservationists, historians and neighborhood activists who were trying to get several of Tin Pan Alley’s historic buildings on 28th Street designated NYC landmarks.

When did it move uptown, and why? When did songwriting change, and how?

As theaters moved up Broadway to “Longacre Square,” soon to be retagged Times Square when in 1904 The New York Times erected its publication headquarters at the crossroads of 42nd Street and Broadway, attracting many of the city’s music publishers to the area as well. The Brill Building, among others mingled within the theater district, soon became the mid-20th century’s Tin Pan Alley district and the home of America’s theater and popular music production.

Currently, the music industry is widely dispersed. However, I compare ragtime music and its evolution and influence into American jazz and popular music as being akin to hip hop. Originally, their sounds and identities were outside the American cultural mainstream, yet it caught fire with the rising generation.