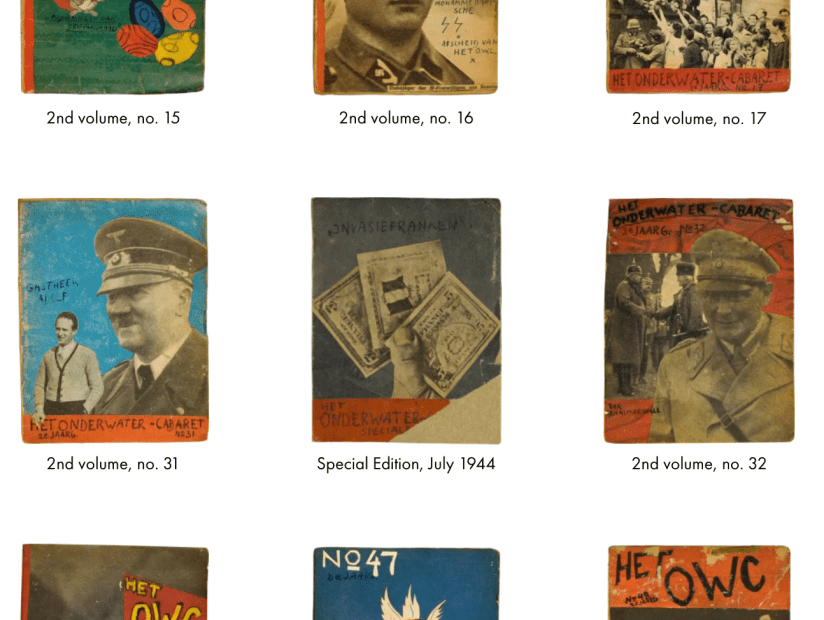

From August 1943 until the end of World War II in April 1945, Curt Bloch, a German-Jewish refugee hiding from the Nazis in the Netherlands, produced 96 issues of Het Onderwater Cabaret (The Underwater Cabaret). It was a one-of-a-kind handmade arts and satire journal—illustrated, written and bound—that could only be read by one person at a time. Bloch’s covers were stylized photomontage, inspired by antifascist satirical magazines, including AIZ, known for its anti-Nazi illustrations by John Heartfield.

The journals included original art, poetry and songs that often dangerously took aim at the Nazis and their Dutch collaborators. Bloch, writing in both German and Dutch, mocked Nazi propaganda, responded to war news and offered personal perspectives on wartime deprivations. All this achieved not by a trained artist, but a lawyer.

Bloch survived the war, as did fragile copies of all the journals, which he brought to New York City and kept in his apartment. There they sat on a shelf in bound volumes until they were discovered by Bloch’s daughter, Simone, a psychotherapist. Her efforts to tell the story of Bloch and his work led to a book, The Underwater Cabaret: The Satirical Resistance of Curt Bloch, by Gerard Groeneveld, which was published in the Netherlands in 2023. Last week, in collaboration with the distinguished design historian Thilo von Debschitz, a museum exhibition, ‘My Verses Are Like Dynamite.’ Curt Bloch’s Het Onderwater Cabaret, opened at the Jüdisches Museum Berlin. Von Debschitz is also responsible for an ambitious website dedicated to Bloch’s heroic achievement.

When von Debschitz introduced me to Het Onderwater Caberet and Simone Bloch last year, I was excited to extend an invitation to interview both. They chose to wait until the opening of the JMB exhibition last week.

The Underwater Cabaret brings to mind Anne Frank, though Curt Bloch survived. How was this incredible collection preserved and rescued?

Simone Bloch: Curt and the OWC [Underwater Cabaret] remained safe during the war. “Rescue” for both came with liberation in 1945. We’re not sure how extensively OWC circulated, but we do know that it was published weekly and returned. How many visits it made [to individual readers] before Curt got it back is uncertain. For a time Curt “published” a weekly magazine exclusively for Karola Saunders called Secret Service, in hopes of winning her love. She loved his words but not him. She kept Secret Service, and in 2023 her son Robert Saunders donated them to JMB.

After the war Curt had OWC bound into volumes in Amsterdam. He brought them with him to New York in 1948.

Thilo von Debschitz: The magazines circulated within the resistance network of Enschede and were returned to Bloch after being read by other people in hiding and their supporters. Curt collected all magazines and took them with him when he emigrated to the United States. He had all the issues bound into four books. These books stood on the shelf of the Bloch’s home for decades.

It is clear where many of his collage materials came from. These are carefully cut from newspapers, magazines and books, and many of the images are valuable historical documents today. How did Curt do the actual work on these issues? Where did he obtain the raw materials?

von Debschitz: The supporters of the resistance network provided German and Dutch magazines and newspapers to him. Curt Bloch used glue and scissor to create the collages. He handwrote the poems with a fountain pen. Then, he thread-stitched the pages.

Bloch: There are also poems that complain about the lack of raw materials and poems that praise his supporters for having delivered a new supply of material to work with. To support the troops, Germans were asked to send their magazines “to the front” for the soldiers’ entertainment, so magazines were precious supplies. Curt mentions shortages of paper and of “news.” Also weakening of will. Some time in 1944 he says it’s the last issue. But then, a week later there’s another and he keeps going.

Who did he trust to show these one-of-a-kind magazines to?

von Debschitz: While the curators of the exhibition in Berlin assume that the magazines never left Curt’s home, the historian Gerard Groeneveld (who took far more time than the curators to examine the circumstances) is very sure that the magazines were given to other people. In fact, his guess is that up to 30 people might have belonged to his readership. He wrote to me:

I had to derive about the readers from what I have found in the archives and in basis what Curt Bloch tells about that. The numbers are of course an estimation on my part. Bloch didn’t stay only in the Plataanstraat, he moved to other addresses as well. There are at least three people who testified about his anti-Nazi writings: Leendert Overduin, Jeronimo Hulshof (at whose house he stayed few months before he was liberated) and Annie Hommes, also from Borne.

He thanked his readers for the newspapers and magazines they delivered to him in the poem “Bedankje voor geïllustreerde bladen” (OWC, Tweede jaargang, nr. 35, 9 augustus 1944). And lastly, in a letter to his uncle Gustav Kramer, dated 28 May 1945, Bloch states about his poem production that he has read in small circles repeatedly his poems, which were “always a success.”

These findings are factual and more elaborated than the assumption that the OWC never left the house

Bloch: I wish I knew more than I do. I wish I’d asked more questions.

There is a decidedly tutored look to The Underwater Cabaret. When I first saw some issues, I was fooled that they were not printed. Was he a designer or editor prior to the Nazis?

von Debschitz: No. He studied law and was about to start a career as a judge. But the Nazis came to power, and all Jews working in the field of law had to quit their jobs.

When Curt was still a student, he wrote some articles in the Dortmunder Generalanzeiger, Germany’s biggest newspaper outside of Berlin; so he had some experience in writing.

Every OWC issue is handmade and unique.

Bloch: Curt had no formal training in design, but his father was a sculptor who came from a family of stone masons, I think. They were assimilated non-religious Jews but not upper crust. Art and design and aesthetics and an appreciation of nature were definitely a presence in the house but not consumerism. I think Curt’s eye was trained by exposure to the art and design of his time. I learned from him to look critically without being taught what I should see. Somehow I believe that is how he was taught to “see” by his father, but I have no proof.

As a teenager, I worked for American “underground” periodicals. There is a visual (and probably a philosophical) similarity. What was Curt’s motivating force?

von Debschitz: I’d say … not to become silenced. Standing up against oppression. Commenting on fake news of the Nazis. Using satire as a weapon. Entertaining and impressing other people in hiding. Creating social interaction [while] being locked away in isolation.

Bloch: I agree with Thilo on Curt’s motivating force while in hiding. Curt was born in 1908 and came of age at a time when revolution of all kinds seemed possible and desirable. Dismantling inequity and rethinking power structures was in the air, very much like the ’60s, when you came of age.

Unlike my foray into contraband publishing, even though I was arrested twice I knew I would never be killed for it. But Curt faced terrible fates if caught. Why did he continue?

von Debschitz: He trusted in the network, I guess. On the other hand, he was fully aware that his editorial work was dangerous. In a certain poem (“Ein Ziel,” from issue no. 5, 2nd volume, 1944) he comments on a trial in Germany. Four people were sentenced to death because they distributed one single poem mocking Adolf Hitler. He writes:

Four lives for just one poem,

I ask myself with surprise,

What would happen to me,

I have nearly four hundred.

Bloch: To me it’s a more absurdist/existential/defiant stance. Why not continue? What else did he have to do? He was trained as a lawyer and ironically his existence had been made illegal by the stroke of Hitler’s pen. He had little to eat, nowhere to go, and if he was discovered he and his protectors would all be dead. Yet somehow he had all these rhymes in his head. Like Tupac—his existence itself has been criminalized. The only thing to do is call out the injustice. Just not too loudly.

Simone, did he ever talk to you about these things? You are a psychotherapist. Does this impact your work in any form?

Bloch: My father died suddenly when I was 15. At the time I was busy rebelling against him and the strictures he was trying to place on me as a parent. That’s one of the reasons I entered the field of social work and became a psychoanalyst; to understand where he (and therefore I) came from—culturally and otherwise. As an analyst I seek to understand with compassion, yet continue to probe pain and where it comes from. I learned that from my parents, and that’s how I share my inheritance.

What do you hope will be the result of making this material public? What was the response from the New York Times coverage?

Bloch: That’s a really big question. Now that the exhibit at the Jewish Museum Berlin has opened, in addition to the Times there’s been quite a lot of coverage in the European press, most especially German, but also Greek, French and Hebrew. I believe we’ve begun to fulfill my father’s wish that his voice as a poet could educate and entertain. He used creativity, critical thinking and humor as tools to face uncertainty and injustice, and I hope our website can inspire people in dire circumstances not to give up or feel forgotten. I wish he could have seen the way that Thilo has taken The Underwater Cabaret off the shelf and created curt-bloch.com to make his work available to anyone anywhere.