What happened when the popes and monarchs of yore were major patrons of the arts? Sometimes great artists emerged. Throughout history, magnificent works glorified God as well as the kings, queens and aristocrats who commissioned such pieces for their own pleasure and status. Priceless masterpieces, the treasures of today’s cultured world, could not have been created without the indulgence of an absolute ruler. Yet the patron’s intervention was not always a boon to the cause of art. Bad and mediocre was and is more common than great. Twentieth-century art bears this out, notably with the injection of ideology and “nationalist” propaganda masquerading as fine art.

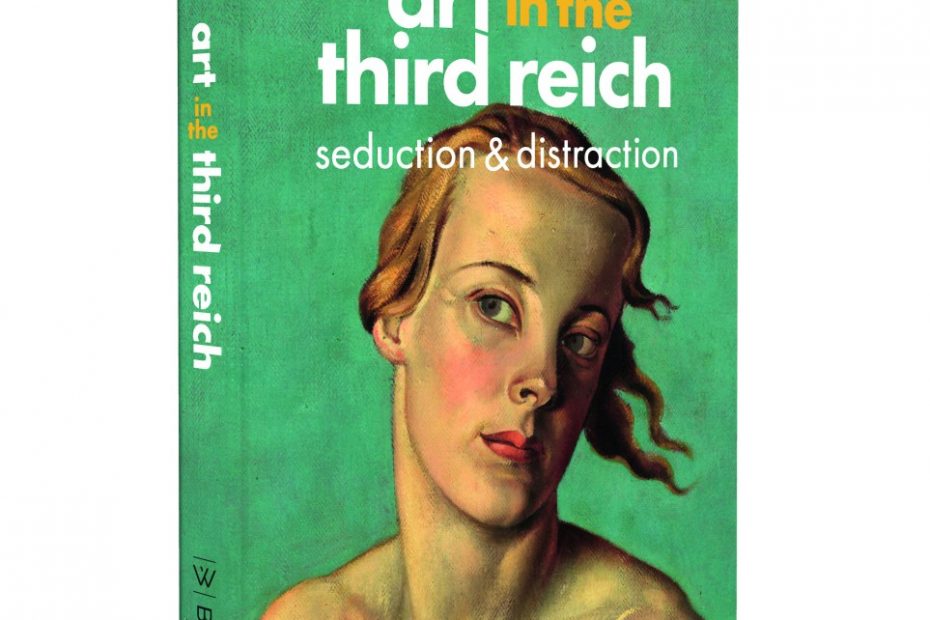

In a recent Museum Arnhem exhibition and book, Art in the Third Reich: Seduction & Distraction, curators/authors Jeller Bouwhuis and Almar Seinen explore the prejudices and preferences of Adolf Hitler as curator of the Third Reich’s artistic styles, movements and schools—his belief in the rightness of exactitude in idealized and mannered representation, and his vehement hatred of experimental and avant garde approaches. Although many loyal Nazis had a diversity of perverse interests that included Modernism, the dictatorship imposed official Nazified taste and denigrated or forbade the rest. German “volk” were indoctrinated through sanctioned annual traveling art exhibitions, often overtly curated and, not incidentally, featuring a large proportion of pieces owned by Hitler himself.

Seinen’s historical research astutely leans toward the underbelly of culture and art. This particular theme is addressed in our interview that focuses on the proclivity for art, architecture and design that conforms to Hitler’s view of his own place in history. Joseph Goebbels said that Hitler’s first love was art, but he was driven by his duty to restore Germany’s greatness. After he succeeded at that, Goebbel’s asserted, Hitler would return wholeheartedly to making art. I spoke to Seinen about the demigod’s mission and unwavering imposition of his tastes—and the curious revisionist qualitative nuances that arose in the art world of Nazi Germany.

What inspired your scholarship of Nazi-era art and artists?

I am interested in the margins of art history, in the stories we prefer not to tell the reasons why some art is—and other art is not—seen and canonized as “real” art. The fact that art is politically controlled, even today, does not fit in with our contemporary idea of the independent, autonomously operating artist. All these issues about how we relate to visual art, who is and who is not allowed to participate, who we cancel and the reasons behind it, it all comes into play if you study the art of the Third Reich attentively and with an open mind.

Albert Kanesch, Watersports, 1936.

There have been books about Hitler’s propensity for heroic realism and romantic representation. What did you learn that adds to this body of knowledge?

Hitler’s personal preference, or taste, is often seen as limited and mediocre—petty bourgeois genre paintings, romantic landscapes and historical painting. Broadly speaking, this view is correct, but I think it is good to separate Hitler’s personal preferences from how he saw the role of art in his Germany. Art had to be clear, recognizable, appealing, narrative, optimistic and, above all, expertly made; within these parameters there was a lot of room for artists, even for Modernist experimentation, as Gregory Maertz explains in Nostalgia for the Future.

Günther Donich, German Loading Station, 1939.

The Nazis plundered some of the greatest art in the world. How do you explain their affection for “nationalist” art?

Hitler saw the German people and the Aryan people historically as great culture bringers and culture creators. To underline this, art and cultural treasures from all over Europe were selectively stolen, looted and purchased to be widely displayed in, among other places, the large Führer Museum in Linz. The visual arts that would flourish again under National Socialism had to stand and continue in the tradition of all these old masters.

House of German Art, 1937.

Was there any artist or piece of art that surprised you?

To compile the book and the exhibition that I made in Museum Arnhem, I went to see as many works as possible in real life. Like most of us, I knew the works mainly from books, and then only as small black and white images. Being able to see and study all the works in real life turned out to be really important, and in many cases was very surprising. I have tried—however difficult it is—to forget under which regime the works were created in order to have as neutral a view as possible. When you succeed in this, you suddenly see completely different things. You see brush strokes, craftsmanship, passion, even virtuosity. To your surprise, you see that there is indeed quality in these works that have been canceled by art history. Some works are simply of high quality. I was and am most impressed by the paintings of Edmund Steppes, a painter who weaves together Romanticism, Symbolism and Magical Realism in an inimitable style. All of the works exhibited by Steppes at the Grosse Deutsche Kunstausstellung were purchased by Adolf Hitler himself, which just goes to show that there is more to the art of the Third Reich than we want to know.

What has happened to the majority of these artworks?

After the Second World War, a lot happened that caused art from the Third Reich to be consigned to art history obscurity. Art that is associated with a pernicious regime is replaced by good art that is at odds with it in content and form. Just like Entartete Art before the war, Nazi art was now banned from museums and locked in the cellar.

Art From The Front Exhibition, 1941.

The artists presented in the German art exhibitions were clearly skilled, but other than technique was there any substance to their work?

Our idea of what Nazi art is is based on a handful of works that were taken by the Americans as war booty and thus remained visible in the public domain. Many thousands of unknown artists and works of art still need to be traced and studied to get a true picture of what Nazi art actually was. But no one wants to embark on this quest, and as long as this does not happen, the image we have of art from the Third Reich will remain stubbornly maintained. With the book and the exhibition I have tried to nuance the image of this art by dealing with it, actually for the first time, in a more neutral art historical way.