Walk through any American city during election season, and you’ll see it; politics rendered in pixels, posters, and typography. Campaigns have become brands, each vying not only for our votes but for our beliefs. In an age where trust is fragile and attention fleeting, design has quietly become one of democracy’s most persuasive forces.

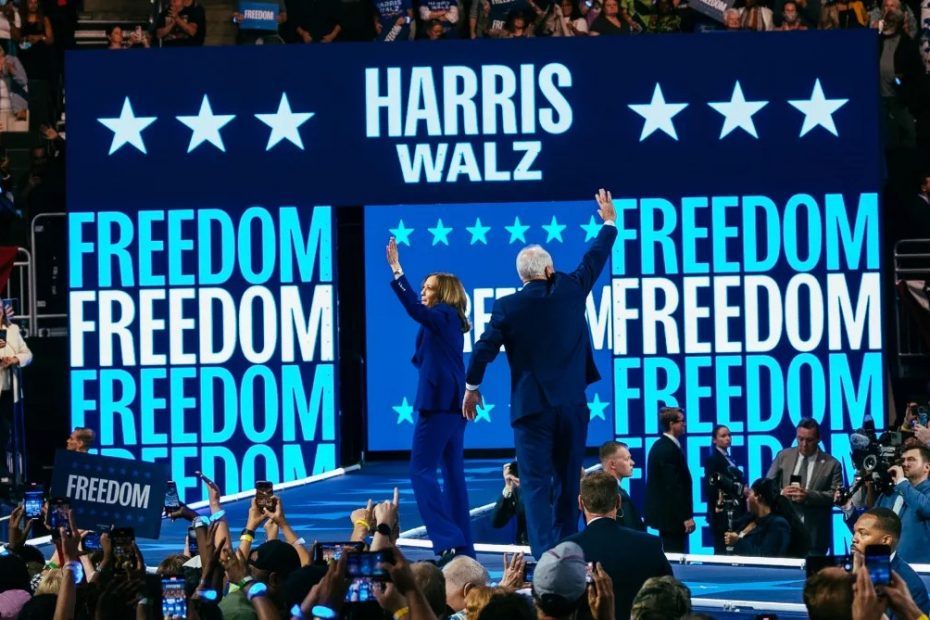

We tend to think of campaigns as ideological contests, but they’re also aesthetic ones. The way a candidate looks, speaks, and shows up visually tells us as much as their policies ever could. Across the United States, candidates are learning that visual identity can do what policy alone cannot: build trust, evoke emotion, and communicate belonging. We’ve seen it in the bright optimism of Kamala Harris’s 2024 presidential campaign — the vibrant, typographic palette, a nod to Shirley Chisholm’s groundbreaking 1972 run — that design has evolved from a campaign accessory into a political strategy.

Left: Harris Walz campaign visuals from Kamala Harris’ website, Right: Shirley Chisholm 1972 campaign poster from The Library of Congress

Consider the recent energy surrounding Zohran Mamdani’s campaign in New York, whose design language felt more grassroots than traditional politics. His visual system—a confident blend of community-forward photography, modern typography, and bold color—did more than advertise a candidate. It redefined what political branding could feel like: local, human, and alive. So much so that Mamdi’s opponent in the mayoral race, Andrew Cuomo, recently updated his campaign branding to follow suit. That same spirit is beginning to ripple across the landscape of American politics, where design is no longer a veneer but the message itself.

Visuals from Zohran for NYC Instagram campaign

Left: ‘Cuomo for Mayor’ before visuals from Facebook campaign; Right: ‘Cuomo for Mayor’ after visuals from Instagram campaign

And we’ve seen it, too, in the enduring simplicity of “MAGA,” one of the most powerful pieces of political branding in modern history; proof that repetition, color, and clarity can anchor an ideology as forcefully as any speech.

Even Trump’s appointment of a chief design officer underscored the cultural shift. Design has entered the political mainstream, influencing not only how campaigns look, but how governance itself is framed. Whether used to unite or divide, design now shapes the emotional architecture of democracy. It tells us who we are, who we trust, and what future we’re willing to imagine together. What was once dismissed as superficial is now strategic. Design has evolved from a campaign accessory into a political strategy. It’s the visual shorthand for belonging, belief, and identity.

To explore this evolving relationship between design and democracy, we asked some of the most influential voices in branding and civic storytelling: What is the role of design in U.S. politics?

(Contributor comments lightly edited for length and clarity.)

Left to Right: Min Lew, Jessie McGuire, Jen Yuan, YuJune Park, and Caspar Lam.

Min Lew, partner at Base Design:

Designers working in politics carry real responsibility.

Design isn’t decoration. It’s a way to communicate ideals and move people. History shows just how powerful it can be: J. Howard Miller’s “We Can Do It!” poster (1943) lifted morale and later became a symbol of empowerment; the “I Am a Man” poster (1968) for the Memphis Sanitation Workers’ Strike crystallized demands for dignity and justice; Shepard Fairey’s HOPE poster (2008) became an emblem of Obama’s campaign and a cultural touchstone.

These works didn’t just persuade, they shaped how people thought, felt, and saw the world. Today’s designers inherit that same responsibility.

Political design turns ideals into imagery. The best work does more than convince. It invites people in, helping them feel part of something bigger. In a noisy, fragmented media landscape, design can cut through, speaking to emotion before intellect.

Design doesn’t decide politics, but it shapes how politics is perceived, and perception often becomes reality. The real question is how the design can be done thoughtfully, with integrity, and with intention.

The best work does more than convince. It invites people in, helping them feel part of something bigger.

Min Lew

For the People Project by ThoughtMatter

Jessie McGuire, managing partner at Thought Matter:

The last twenty-five years have been a masterclass in how design shapes democracy.

The twenty-first century started with Helvetica and hanging chads, the butterfly ballot that woke up America to the fact that bad design could break a nation. From there, we learned to make politics beautiful. And, dare I say, brandable.

Obama’s 2008 campaign turned hope into a logo, and Shepard Fairey’s poster became the new political creative bar. Suddenly, design was politics, the image and the emotion fused together to inspire dreams.

But we know beauty can be blinding. The same design culture that elevated belief also professionalized it, turning civic life into a marketing brief. By 2016, the cracks showed.

Clinton’s mark was perfect, geometric, global, and cold. Trump’s hat, on the other hand, was everything design schools teach you not to do: loud, cheap, legible from a mile away. That was the point. It was designed for rage, for belonging, for television, and for the sharpie.

Now, in 2025, the energy feels different. In New York City, Zohran Mamdani’s campaign looks like it was born on the streets of New York; in the hands of people, not consultants. Its colors echo protest flyers and deli awnings. Its typography feels lifted from the city’s walls. It feels alive because it’s built from the same textures that make the city breathe.

It’s the kind of visual noise democracy makes when people believe again, which is the point. Mamdani’s campaign isn’t trying to be timeless or iconic; it’s trying to be of its time. It reminds us that good political design needs to matter right now.

Graphic designers love to talk about timelessness, as if the air of permanence proves value. But in politics, timelessness often serves the powerful. It freezes the moment; keeps it tidy, controllable, and unchanging. Timeliness, on the other hand, meets the moment, often with messy, participatory design language; one that belongs to everyone who shows up.

Design should not be the polish of power, but rather the pulse of belief. Democracy should be imagination in action. Our job as designers isn’t to make it look perfect, it’s to make it feel possible.

Design should not be the polish of power, but rather the pulse of belief.

Jesse McGuire

Jessie McGuire and the Where Democracy Begins project by ThoughtMatter

Jen Yuan, partner at View Source:

We should not use design to persuade people toward a particular viewpoint; rather, we design to help them understand enough to make informed decisions for themselves.

As a partner at a creative studio that blends digital expression with human sensitivity, I often find myself thinking about design in civic terms.

Having lived and worked in New York, Paris, and Taipei, I’ve come to see each city as a different experiment in how people make sense of power. In the U.S., design often strives for clarity. In France, it engages in debate. In Taiwan, it facilitates cooperation.

Across all these contexts, a common thread exists: design is how societies maintain a conversation with themselves. When that conversation falters, cynicism fills the silence.

Every choice – from typography and interaction design to microcopy – shapes whether people feel informed or excluded. Design can make complex systems legible and approachable, or it can make them feel impenetrable. In political contexts, thoughtful design is not about persuasion; it is about creating understanding and fostering meaningful engagement.

Design is how societies maintain a conversation with themselves.

Jen Yuan

Where Democracy Begins project website by ThoughtMatter

Caspar Lam and YuJune Park, co-founders and partners at Synoptic Office:

Politics is fundamentally about the activities of governance. Embedded within this is a need to communicate, to persuade, and to comprehend. It’s about ideas, belonging, and expectations of the future.

Design has a huge role in shaping the infrastructure and delivery of these ideas among stakeholders within a political system. Design often shows up as a brand for campaigns or interfaces for voting systems, but it is just the visible tip of a larger strategy and system.

Because design acts as an intermediary messenger between the government and the people, it has a role in conveying the fidelity of the message. A messenger can amplify a message by shouting it to the world, or a message can become lost and confused, which means that it might never reach its recipients. The difference is between an informed and a misinformed or uninformed citizenry.

Designers must understand that they are designing for the public, and to broaden the reach to as many people as possible, the design constraints become much greater and more challenging.

In a digital context, much of the design surrounding government and politics focuses on reliability and accessibility – both of which are fundamental and non-negotiable requirements.

However, design has soft power in its ability to subtly shape mood and feeling through typography, color, and form.

These are qualities that are harder to quantify but speak to citizens as human beings. Here, user experience design, when artfully deployed, can impart the nation’s values and foster feelings of civic pride and responsibility to encourage participation.

Because design acts as an intermediary messenger between the government and the people, it has a role in conveying the fidelity of the message.

YuJune Park and Caspar Lam

In the end, design’s influence on politics runs deeper than campaign aesthetics or catchy slogans; it’s about shaping how we see ourselves within the larger story of democracy. Every color choice, typeface, and image becomes a mirror reflecting not just a candidate’s identity, but our collective hopes and fears. As campaigns evolve into brands and ballots become acts of visual communication, design emerges as both a tool and a responsibility: to clarify, to connect, and to challenge what power looks like. Because in a democracy built on imagination, the future isn’t only voted for — it’s designed.

Where Democracy Begins project by ThoughtMatter

About the contributors:

Min Lew

Born in Germany and raised in Seoul, Min Lew now resides in Brooklyn, New York. She brings 20 years of diverse experience across culture, technology, luxury, fashion, and more. As executive creative director and managing director at Base NYC studio, Lew merges strategic insight with artistic flair, working closely with industry leaders to boost cultural relevance and lasting impact. Lew’s knack for quietly absorbing, analyzing, and contextualizing before speaking makes her appear a silent observer. But when she does speak up, her words pack a punch, effortlessly grabbing everyone’s attention. Her impressive portfolio includes collaborations with key players like Apple, The New York Times, JFK T4 Terminal, and MoMA.

Jessie McGuire

Jessie McGuire is managing partner at brand design studio Thought Matter, leading a team of artists, writers, and strategists to create daring designs and identities for everything from art museums, communities, and brands to a range of institutions and organizations. She has been integral in shaping the purpose and creative vision of Thought Matter, spearheading projects and campaigns that reflect the agency’s culture and mission, including protest posters for the 2017 Women’s March, a modern redesign of the U.S. Constitution, and the recently launched For The People docuseries. McGuire has also worked to raise awareness and support for socially progressive causes such as March for Our Lives, Girls Write Now, and The Joyful Heart Foundation, as well as on community-minded projects for The New-York Historical Society, Downtown Staten Island, and The Center for Arts Education.

Jen Yuan

Jen Yuan, partner at View Source, drives strategic vision and operational excellence. His pioneering work in template design is utilized by prestigious organizations like UNICEF, Nasdaq, and Pokémon. Working across diverse sectors, Yuan crafts tailored solutions for high-profile clients from recording artists to media personalities. As a jury member for FWA – one of the internet’s most distinguished website award programs – he shapes the future of digital design while bringing sophisticated approaches from concept to execution.

Caspar Lam and YuJune Park

Synoptic Office is an award-winning design consultancy that works globally with leading cultural, civic, and business organizations to communicate ideas, build experiences, and cultivate new audiences. As experts in digital strategy, user experience, and creative direction, YuJune Park and Caspar Lam help institutional partners transform complex information into meaningful narratives and experiences. The studio’s work has been honored by Fast Company’s Innovation by Design Awards, The Webby Awards, the Art Director’s Club, and the American Institute of Graphic Arts.

The post The Design of Democracy: How Branding Shapes the Battle for Belief appeared first on PRINT Magazine.