Three people I owe so much to as a writer, and the big change that’s coming thanks to them.

Dee O’Brien and the Magic of Words

Dee O’Brien was the teacher who made an eighth-grader fall in love with Shakespeare, Emily Brontë, and Kate Bush. She taught with a voice bigger than her body, and a persona far bigger than her voice.

She could recite sonnets from memory and wore purple as a rule. Sometimes, while reading a passage out loud in the wonderfully exuberant way that she did, her long black hair fell to the front and covered her chunky Lucite 80s jewelry. She’d flip it back, and I could stare at her earrings again. Even the braces on her teeth seemed cool.

I didn’t just want to please her, I wanted to be her.

She let us call her “Dee,” like we weren’t 12- and 13-year-olds. Like we weren’t worthy of the disdain the new seventh-grade English teacher had made me feel the year before.

She didn’t read poetry; she performed it until it became something breathing and vivid and wholly alive. She invented mnemonics to help us memorize relative pronouns and taught us to sing subordinate clauses to the tune of “Deck The Halls.”

An invitation to spend lunch with her in her classroom was more than a respite from a chaotic middle school cafeteria with its smell of old mops and sad, soggy rectangular pizza slices. Lunch with her was like the greatest fifty-minute field trip. There would be music. There would be discussions about our home lives and the trials of adolescence, divorce, unrequited crushes. If it happened to come up, there would be the proper pronunciation of iambic pentameter.

I did not dress the part of the preppy A-student of the 80s, and I talked too much in class, but unlike that other teacher, Dee refused to be fooled.

She cast me as Helena in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and when I cried because I wasn’t playing the beautiful Hermia, she helped me see that I would have all the funny lines. Which I really did.

Stay, though thou kill me, sweet Demetrius!

Every year, she swore it would be the last year she’d put on two full-length Shakespearean plays with middle schoolers. It never was. Even after she retired. The Semi-Royal Shakespeare Company became the country’s longest-running continuous youth Shakespearean troupe. (I suppose even Dee O’Brien couldn’t quit Dee O’Brien.)

She helped us see that we were not unique in our pains, our heartbreaks, our struggles — those stories had been told for centuries, and we were allowed to step into them as Helena, as Titania, as Rosalind, as Caliban. Bawdy double entendres and all.

When I saw her face on social media for the first time as an adult, I burst straight into tears because I had never stopped thinking about her, and here she was.

Dee O’Brien taught me to love language. She taught me the magic of words. Dee O’Brien made me want to be a writer.

Duke Schirmer and Tenacity

Duke Schirmer was the creative writing teacher who made a high school freshman feel like maybe she really could write things that made people feel something.

He used no textbook that I can recall, no rote lesson plan, no tedious quizzes about SAT words. He flitted from desk to desk, shouting inspiration or rallying us around a new idea. He often read student work out loud, with deep emotion, and sometimes with tears in his eyes. He read it all as if it were brilliant — perhaps because he could truly find the spark of brilliance in any of it.

When he had something really important to say — which was all the time — he got quieter. He crouched down low to the floor, elbows resting on his knees, the hems of his chinos rising up to his calves. He drank dark coffee and swore. He lit cigarettes right in class.

This skinny man with the glasses and the khakis in his last year before retirement: He was the most rock-n-roll person we’d ever know.

He handed out index cards at the end of the school year and told us to choose our own grades for our report card, because, after all, it was the work and not the grade that mattered. Most of us struggled mightily with the temptation to ask for an A we hadn’t legitimately earned; it would cost his esteem, and that was too high a price.

I settled on an A-.

Mr. Schirmer made us write every day — in class and then later at home — until for me, it became something more than a habit, it became a necessity. He taught me the concept of freewriting — when you’re stuck, you just write and write and write until you find the thing you want to say.

Still works.

(Case in point: This essay started as something else entirely.)

A few years ago, Jon helped me finally clean out an old storage locker, where I found a banker’s box filled with weathered papers and files, including a fat manilla envelope sealed with a kraft clasp. I opened it, and out poured pages of writing from his class: My freewriting. My children’s story final assignment was deeply inspired by L. Frank Baum. My surprisingly good (if disconcertingly rage-filled) poem about a mean girl I hardly remember now.

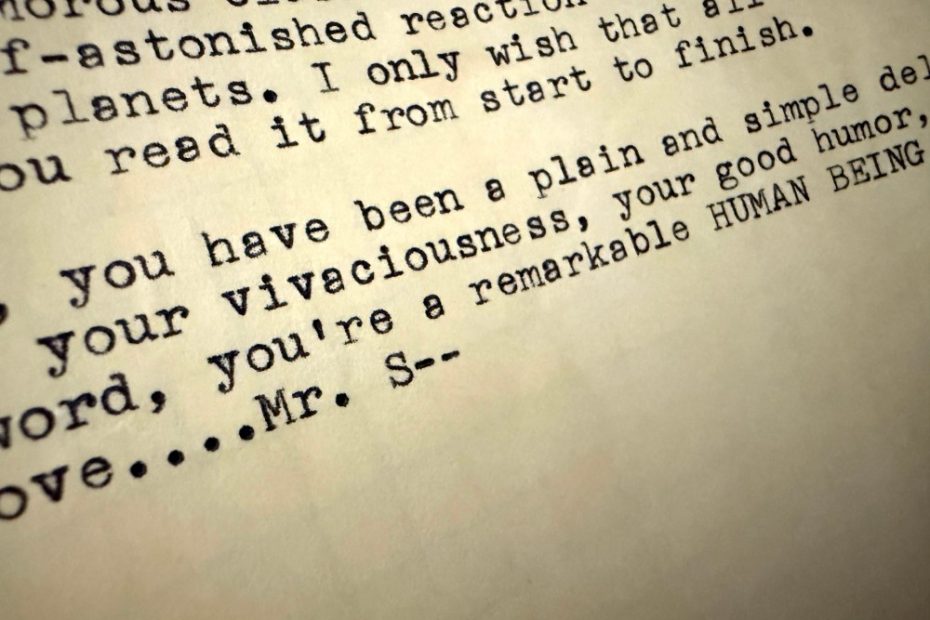

What took me most by surprise were not my words, but his own — the amount of time and thoughtfulness he put into more than a half-page of single-spaced, typewritten comments was astounding.

I was never known as the best student in school, and I certainly don’t remember myself as particularly seen by most of my teachers. So I was moved to discover this note from him at the end of his comments:

For me, you have been a plain and simple delight for the past 20 weeks. I love your vivaciousness, your good humor, your profound responsiveness. In a word, you’re a remarkable HUMAN BEING, dear friend.

He was our John Keating before there was a John Keating. He was our O Captain My Captain.

Duke Schirmer taught me tenacity. He taught me fearlessness. Duke Schirmer made me want to be a writer.

Image courtesy of the author

Walter Lubars and the Meaning of Mentorship

Walter Lubars was the advertising professor who made the secretly insecure sophomore in the front row center of the college classroom know that she was exactly where she was supposed to be, and more so, that she deserved to be there. Even with her lingering insecurities after an Early Decision deferral, and some borderline SAT scores that must have been monstrously outweighed by an entertainingly self-deprecating application essay about an exchange trip to France.

He was paternal, warm, wryly funny, and sharp-witted, but never mean. He held onto his New York accent, which brought more life to his stories about the old days of Madison Avenue, crazy clients, and three-martini lunches, which, as it turns out, was an extremely real thing.

(This had turned into two margaritas by the time my first mentor in the business took me to lunch. Today, it’s more like a cup of lukewarm Keurig coffee while you eat alone at your desk.)

His was the advertising creativity class that you’d drag yourself out of a sick bed for. He made advertising so fun that every assignment was a genuine treat. His lectures took delightful detours into stories about his wife, his kids, his favorite movies, his most successful students, and the colleagues he clearly loved a great deal.

He was hard on my writing, and that was an incredible kindness.

“It’s good,” he’d say. Then, after a long pause, “But you can do better.”

Years before I arrived, he had created Boston University AdLab, the country’s first student-run ad agency and the primary reason I wanted to study at BU. He made me an associate creative director as a junior, setting me up to be the creative director/copy as a senior. He gave me the confidence to manage 100+ people my own age. He taught me how to be critical and still be encouraging.

He became my faculty advisor and tipped me off to the best internships. He taught me how to defend my work. He gave up entire office hours to look at my portfolio work, or sometimes just sit and talk.

Spring before graduation, I was fortunate to be deciding between two job offers and peeked into his office to get his opinion. He motioned for me to come in and shut the door, then he offered some advice that he warned I should never repeat, but that he felt he had to tell me.

I believe I owe my entire career to those words.

(And no, I won’t tell you!)

My favorite photo from commencement is one of Walter hugging me up on stage.

We stayed in touch for years afterward, having long phone calls about the business and his students, his pride in his kids, his delight at being a new grandfather. He continued to advocate for me when my career was going in a not-so-good direction and mentored me back on track. We occasionally grabbed an in-person coffee when work took me to LA, where he had moved after retirement.

The last time I saw him was a huge Zoom call during the pandemic, a memorial for another of many professors at BU who had meant a lot to so many of us.

This past year, in early October, Walter died after a good, long life well-lived. It still hit hard.

Walter Lubars taught me the meaning of mentorship. He taught that writing meant rewriting. He taught me that I had a chance to make it as a copywriter if I worked for it. Walter Lubars made me want to be a success.

Professor Gumbinner

Soon after Walter had died, I was reminiscing about him with Tobe Berkowitz, another former professor, turned invaluable mentor, turned dear friend.

We talked about the other extraordinarily caring faculty members who were now gone, and how many of their own students had stepped into their shoes to become the next generation of inspiring professors — the ones whose classes you’d never miss and who still get calls from students who have long since left the classroom.

These are the teachers who value their end-of-year thank-you notes more than they value their shelves of Hatch Bowls and Gold Pencils; and if you know creative people in advertising, that’s saying something.

“Maybe this is a sign that I’m supposed to join them,” I laughed. But I wasn’t joking.

“We’ve been talking about this for years!” Tobe said.

This fall, I’m honored to be joining the most incredible faculty at the most incredible communication school in the country.

Professor Gumbinner, Boston University Associate Professor of the Practice in the Department of Mass Communications, Advertising and Public Relations.

We are at such a crossroads in advertising, marketing, technology, and media, let alone in higher education. It’s my hope that I can help in some way grow the next generation of thoughtful, purpose-driven, creative and strategic thinkers who learn to devour culture, obsess over craft, honor inclusivity, bring their values to their work, challenge the status quo, and make their mark on the industry in ways we can’t yet imagine.

Maybe I can be half the mentor that my mentors were to me.

I will have to give grades, of course.

But I will be sure my students know that it’s the work, and not the grade, that matters.

Liz Gumbinner is a Brooklyn-based writer, award-winning ad agency creative director, and OG mom blogger who was called “funny some of the time” by an enthusiastic anonymous commenter. This was originally posted on her Substack “I’m Walking Here!,” where she covers culture, media, politics, and parenting.

Header image by Allison Saeng for Unsplash+.

The post The Most Rock-n-Roll Person We’d Ever Know appeared first on PRINT Magazine.