We’re not saving these signs just because we think they’re cool, we’re saving these signs because they mean something to us, and they mean something to us as New Yorkers, and they mean something to our community.

David Barnett, co-founder of Noble Signs and the New York Sign Museum

In the sign painting community, a cheeky adage that’s espoused to keep sign painters grounded is, “It’s Only a Fucking Sign.” As a sign painter myself, I’ve always prickled to this notion— a sign, especially a hand-painted sign, is so much more than a sign. If “it’s only a fucking sign,” then why do we all care so much?

The folks over at Noble Signs and the New York Sign Museum surely agree with me. Co-founders David Barnett and Mac Pohanka started Noble Signs over a decade ago in New York City as a one-stop-shop where they create all manner of signs from design to fabrication to installation. In doing so, they began to collect old signs, until one day they decided to open their own museum. Thus, the New York Sign Museum was born, housing a vast and ever-growing collection of all sorts of advertising ephemera. An assortment of over 150 signs composes the core of their collection, but they also have other items local businesses had used for advertising, like thermometers, calendars, and match books. Someone recently donated a collection of 400 shopping bags from New York City businesses from 1970s and 1980s.

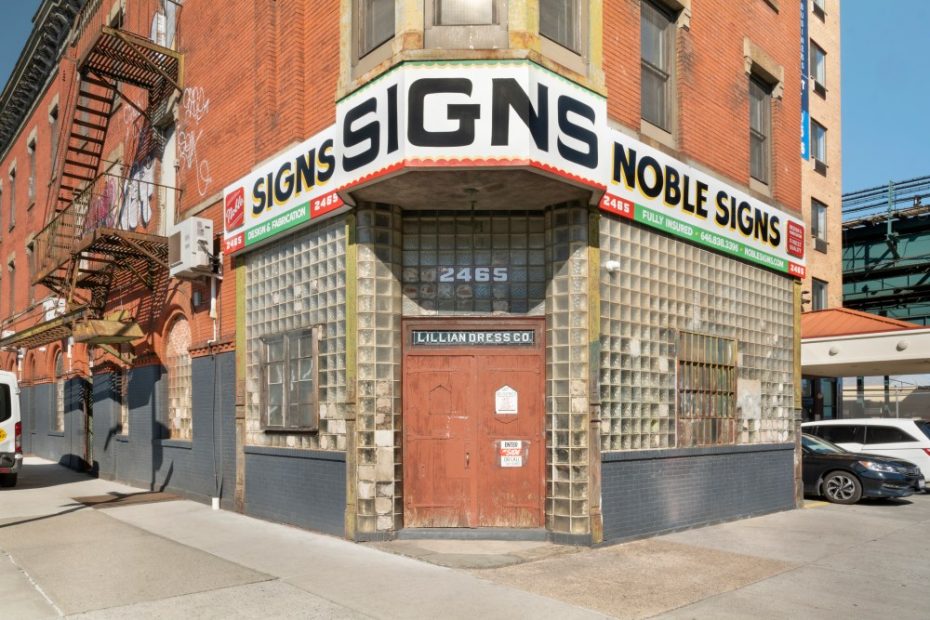

Photograph by Lawrence Sumulong

It’s only been a year since the New York Sign Museum opened its doors to the public, but they’ve already engaged an avid fan-base of visitors who crave authenticity in a world that feels much more superficial than it used to be. Barnett, Pohanka and their team embark upon sign rescue missions when they catch wind that a local business is shutting its doors, and do everything in their power to salvage the store’s sign that is, obviously, so much more than a sign.

I recently had the joy of talking signs with Barnett over the phone, learning more about the intertwined missions of Noble Signs and the New York Sign Museum. Our conversation is below, edited lightly for clarity and length.

Photograph by Phil Gordon

What’s your personal relationship to New York City?

I was born in Queens, both my parents are native New Yorkers, and all my grandparents and most of my extended family lived in the city across four of the five boroughs. When I was a little kid, we moved to North Jersey and I always really wanted to move back to the city; I spent as much time in Queens with my grandma as I possibly could.

Moving made me have a certain appreciation for the city. I have such core memories of the times that I would spend with my grandma in Queens, my other grandma in the Bronx, my aunt in Brooklyn, my uncle in Manhattan… I don’t think growing up I really paid attention to signs, but I definitely always had this love of New York City.

What’s the origin story of Noble Signs? How did you get into painting and fabricating your own signs?

After college I was designing posters for my friends’ bands in Brooklyn, and ended up getting a job at a record label as an art director. I worked there for about five years, doing mostly posters and album art. On the side, a friend who was opening a bar reached out to me to do the logo, and reached out to my buddy Mac—a friend of mine from college who was also living in Brooklyn at the time—to build them a sign using the graphics that I created. Me and Mac were talking, and we were like, “We should just collaborate on the whole project.” And it became a bigger idea of how we could offer full service design and fabrication to restaurant and bar clients, because a lot of people that we knew were struggling to find one partner who could do all of that for them.

Both me and Mac grew up in production families. My dad worked in the printing industry in Chelsea, so I spent a lot of time at the printing press where he worked, which was just a few blocks from Madison Square Garden. And Max’s dad is a fine furniture maker in New England. So we both come from artistic families, but also this blue collar production background as well. So it was very natural for us do this thing that bridged design and craft.

We were just like, ‘Hey, this is so fun! We should just quit our jobs and do this full time.’

We did that one project together, and that led to a couple more. After a few years, we’d done half a dozen projects with Noble (but that was before we had a name for it), and we were just like, “Hey, this is so fun! We should just quit our jobs and do this full time.” Mac was working in the film industry, making props and things in the art department, and the timing with what I was doing in the music industry was fortuitous because everything that I had loved about my job was sort of starting to disappear; people weren’t buying records or CDs anymore, so album art really faded in importance. I was happy to go this other route because what I really love as a designer is designing things and then seeing them through to a physical object that’s going to be made. With album covers and posters, I was creating this physical thing that so many people see, and I always thought that was such a cool feeling. And signs are like that, but so much bigger, the scale of them is just awesome.

Photograph by David Barnett

Can you elaborate on what your mission is at Noble Signs?

We wanted Noble to be a throwback to the way classic signs were made. Old sign shops were this amazing combination of different people, crafts people, artisans, designers, and they were all working together, hand in hand, to make these spectacular things that are so hard to even imagine being made today. A big part of that was the connectivity between design and manufacturing, and having the people who actually make the things also being the ones that design them.

We design with context; with a real sense of local responsibility to keep this unique New York vernacular style alive.

We also love New York City, and we love the unique look of New York City, and so much of that comes from its signage. But even back in 2010 and 2011, it was already starting to disappear. By our third or fourth project, we started looking at the signs around us to inform what we were doing, and trying to create designs and signs that looked like they had a place in New York City. We design with context; with a real sense of local responsibility to keep this unique New York vernacular style alive. So obviously that meant looking at a lot of old signs, studying old signs, and walking down the street and taking pictures of things.

How did you first get into collecting and rescuing old signs?

As early as 2017, I remember a few businesses in my neighborhood closed, and I was like, “We need to try to save these signs.” So that’s when we started really pursuing that angle.

When you make signs and you install them, a lot of the time you have to replace a sign that’s already there. There were a few times where clients would be like, “Oh, will you throw that out?” and we were like, “Throw this out? We’re going to keep this!” We didn’t have a place for them, we were working out of Mac’s apartment at that time, so we were just filling the backyard with old signs. Then we started to actively seek out and save old signs. We didn’t have an end goal in mind, we just wanted to learn about them.

Especially when you get into things like exterior neon signs and channel letter signs, there’s so much that you don’t get from looking at them from the ground. But when you get up close to them or even get inside of them, you’re able to learn so much more about how they were made. And it’s all knowledge that isn’t in books. It was all learned person to person, which is also what gave signs a unique local style; these techniques weren’t something that people were learning from like, “The Big Book of How to Make Neon Signs.” These were things that people were learning from the other people around them, in the cities that they were from, which is why most of the big metro areas in the country have their own unique style. And to me, New York’s is particularly interesting. There’s a certain simplicity about it.

The museum is such a critical part of our mission that it always felt like something we had to do. It was an emotional necessity.

Photograph by Grace Gottesman

Going from salvaging old signs to opening your own museum is a pretty big leap. How did that all unfold?

It was probably 2019, and I just said to Mac, “We should start a museum.” We’re saving all of this stuff, we’re obviously not trying to resell it, we’re not trying to start a vintage shop where you buy old signs— they’re too precious to us, it’s too hard to save them, and they feel too irreplaceable. And in some cases, it would be a betrayal of the people who gave us the signs to sell them.

The museum is such a critical part of our mission that it always felt like something we had to do. It was an emotional necessity. That’s what it was born out of. That feeling of walking down a block you’ve walked down 100 times before, and then all of a sudden the sign is gone. For me, my heart sinks into my stomach. It’s the worst feeling. We’re trying to be a force of resistance against that, which is always tough. Preservation, in general, is a very tough thing to get involved with because you’re fighting against all of the forces in the world. There’s too much interest in things changing and not as much in it staying the same. There’s more money in making new stuff than there is in maintaining old stuff.

There’s too much interest in things changing and not as much in it staying the same. There’s more money in making new stuff than there is in maintaining old stuff.

What can be learned from the signs in your collection at the New York Sign Museum?

What makes the signs that are in our collection so interesting is there’s a unique vernacular style for New York signage, and it has so much personality and local flavor. It represents not just one idea, but all of these ideas, and all of the diverse backgrounds and types of people that live in New York and have always lived in New York. Every sign that you see here in our collection represents a conversation between those real New Yorkers.

Each sign also represents a purer design process than most of us working today know. Obviously the computer is an amazing tool, but at the same time, it gives a lot more room for things to get revised to death, to have that personality sucked out of it. One of the reasons why the signs here are so electric is a lot of them are the product of the sign painter or the sign maker showing up, meeting with the business owner, talking, maybe doing a pencil sketch, and then just coming back with the sign a few weeks later. There wasn’t that design-by-committee. There wasn’t that opportunity for it to get watered down. So there’s something really true and authentic to be learned from looking at these old signs; not just about the ways they were made and the style, but also the design process itself.

Where possible, we try to incorporate that same process into the work we do at Noble. If I can, I’ll give our clients the option of a reduced design rate if we just do a pencil sketch. I’d rather do it that way, if it means that we can do something purer. We look to all of these things to model our own studio practice, and to try to honor that visual language. Starting this museum was really just an extension of that mission in a lot of ways; of trying to keep that personality and character in our streetscape. It’s an archive, it’s a workshop, but it’s also a living art project dedicated to preserving and evolving these lettering science traditions in New York.

We hope that the work we’re doing reclaims this visual language of place. In the world that we live in with accelerating globalization and corporatization, it feels especially important.

Photograph by Phil Gordon

What aspect of the New York Sign Museum are you proudest of?

It can be a resource for designers and for people that want to learn about New York City, but it’s also a way to honor the legacies of the businesses. That’s one of the things about our project that I’m proudest of; we’re not viewing the signs in isolation as a unique object from the perspective of a sign maker. That’s part of it, for sure, but it’s more about the overarching thing of what these signs meant to the community as symbols of the businesses, and what the businesses meant to the community as meeting places, as landmarks, as something that brings meaning to your daily life. When you walk out of your apartment and you see storefronts that reflect your own community as opposed to the same corporate stuff that could be in any city in the world. That’s what’s being lost, and we hope that the work we’re doing reclaims this visual language of place. In the world that we live in with accelerating globalization and corporatization, it feels especially important.

What sort of experience should visitors of the New York Sign Museum expect?

What we lack in polish we make up for in a really authentic experience. You get to see not just the old signs, but you get to see how they were made, and how we are learning from the old signs and using them to define our practice. You also get to see something that’s forming before your eyes. We’re somewhere between an actual white box museum and it just being a bunch of stuff in someone’s attic. There’s that sense of discovery.

We’re somewhere between an actual white box museum and it just being a bunch of stuff in someone’s attic.

Before we started doing tours, I thought people would be judgemental about that. “Why aren’t the signs displayed in a more traditional fashion?” “Why isn’t there extensive labeling?” I thought people would think what we were doing was too raw, but what’s been very cool is people actually love that aspect of it. And now, as we think toward the future because we’ve outgrown our space and we are thinking about what the next chapter will be, I think it’s always going to have to have this component.

It’s not just a collection, it’s a community project. You’re stepping into this workshop where we’re trying to keep this engine of small business and personality and individual expression alive in our streets. We view our mission as having a really high ceiling because it’s just so important and it’s only going to get more important as the forces of change try to strip this away from us. We view this as a way of fighting back. We’re not saving these signs just because we think they’re cool, we’re saving these signs because they mean something to us, and they mean something to us as New Yorkers, and they mean something to our community. When you lose that local character, you end up losing so much of the richness of your experience of living in a city. And we’re not giving up yet!

Featured image above by Phil Gordon.

The post The NY Sign Museum Preserves the Richness of the City by Rescuing its Old Signs appeared first on PRINT Magazine.