The past several months have seen many articles published about the Victorian designer and all-round polymath, William Morris. The focus of the conversation has ranged from William Morris and Islamic Art to William Morris and Kitsch to an exhibition in York, The Art of Wallpaper: Morris & Co. What this recent attention on Morris’s diverse assortment of activities has not mentioned is Morris’s role as a book designer with the establishment of the Kelmscott Press. The Press was Morris’s final artistic project, and the last book he produced for it was also the most celebrated of all: the magnificent Kelmscott Chaucer.

The significance of Morris’s work as a book designer is best explained by the engraver and photographer, Emery Walker, when he wrote: “Morris showed how a printed book might be on its own plane a work of art.” Indeed, Morris’s work with the Kelmscott Press achieved nothing less than enabling us to see books differently.

Described by Morris as his “typographical adventure,” the Kelmscott Press was established in 1891 after Morris had attended a lecture in 1888 by his friend, Emery Walker, called “Letterpress Printing and Illustration.” The lecture inspired Morris to work with Walker and create his own typeface, named Golden. The typeface would be used in the first book published by the Kelmscott Press, The Story of the Glittering Plain, in 1891, which was also written by Morris. With Walker providing technical expertise in photographic reproduction and typographic advice, the Kelmscott Press would go on to produce 53 books in 66 volumes between 1891 and 1898.

Morris was the first to approach the craft of practical printing from the point of view of the artist.

Walter Crane, illustrator

The Kelmscott Press was named after Morris’s Oxford home, Kelmscott Manor, and was originally based in a cottage Morris had rented in Hammersmith, close to his house in London. The Press moved to larger premises next door several months later, in May 1891. The Press aimed to allow Morris to explore and create his “Ideal Book.” Morris lamented the state of Victorian book publishing, considering it to be mass-produced, cheap, lacking quality, and, crucially, reducing craftsmanship to commercial interests. Instead, Morris’s Press would look back to fifteenth-century printing techniques and typography to create books that were hand-printed, limited in number, and which would foreground design and traditional craftsmanship. As Morris’s collaborator, the illustrator Walter Crane observed, Morris was “the first to approach the craft of practical printing from the point of view of the artist.”

In his “Note on the Founding of the Kelmscott Press,” Morris wrote that, “I began printing books with the hope of producing some which would have a definite claim to beauty.” To achieve this, Morris discovered that he had to “consider chiefly the following things: the paper, the form of the type, the relative spacing of the letters, the words, and the lines; and lastly the position of the printed matter on the page.” Morris would develop three typefaces for the Press, these were the previously mentioned Golden, along with Troy and Chaucer – the latter being a smaller version of Troy set in 12 point and used, appropriately enough, for the Kelmscott Chaucer. Each of these typefaces was based on those of fifteenth-century printers such as Nicholas Jensen.

Alongside typography, Morris also had to think about different kinds of handmade paper and ink. The paper, like the typography, was also based on fifteenth-century samples and was provided by Joseph Batchelor and Son in Kent. Three different handmade paper types were used, each with its own watermark designed by Morris. These were called “flower,” “perch” and “apple” and each corresponded to a different paper size. Finally, the ink used was provided by Gebrüder Jänecke from Hanover. To get the ink on the paper, Morris had bought a second-hand Albion Press, to which two more would be installed and purchased in the following years. The Albion Press was operated by hand, in contrast to modern Victorian printing presses which were powered by steam.

Morris designed all the books published by the Kelmscott Press, helped by this close team of printing experts. These included the engraver William Harcourt Hooper, Emery Walker as technical advisor and William Bowden as master printer (along with his son and daughter). Edward Burne Jones, Charles Gere, Walter Crane and Arthur Gaskin provided most of the illustrations. Along with designing the books, Morris also wrote most of them (twenty-three). Other books published by the Press include various medieval works, nineteenth-century poetry, a version of Beowulf, and an edition of Shakespeare’s poems.

The Kelmscott editions are hugely distinctive in their beauty: the juxtaposition of rich typography, decoration, and illustration, alongside their placement on the page, creates an intoxicating visual experience. With them, Morris used the medieval past to comment upon his disappointment with the Victorian printing standards of the present in a way that is all-encompassing, and to demonstrate that books can be conceived differently.

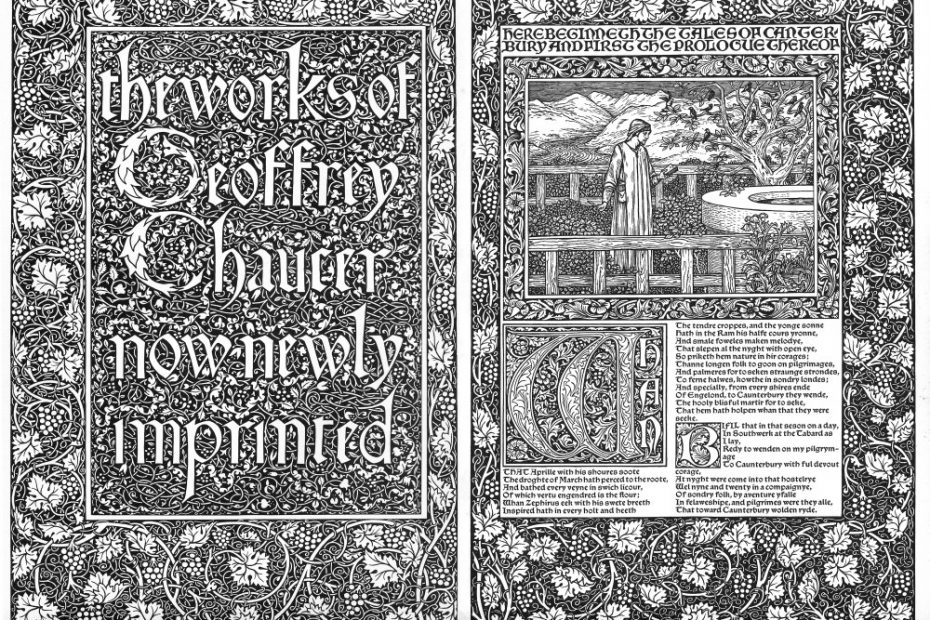

It is a masterpiece of book and graphic design, featuring 87 wood-engraved illustrations by the artist Edward Burne-Jones, as well as 18 frames, 14 borders, and 26 decorative words designed by Morris.

According to Morris’s friend and secretary, Sydney Cockerell, ‘by far the most important achievement of the Kelmscott Press’ is The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, more popularly known as the Kelmscott Chaucer. The book, published four months before Morris died in 1896, has been described by the poet W.B Yeats as “the most beautiful of all printed books,” while a contemporary review observed that “in its own style, the book is, beyond dispute, the finest ever issued,” It is a masterpiece of book and graphic design, featuring 87 wood-engraved illustrations by the artist Edward Burne-Jones, as well as 18 frames, 14 borders, and 26 decorative words designed by Morris. Only 425 copies of the Kelmscott Chaucer were originally produced, alongside 13 copies printed on vellum.

… if we live to finish it, it will be like a pocket cathedral – so full of design and I think Morris the greatest master of ornament in the world.

Edward Burne-Jones

Morris and Burne-Jones had been undergraduates together at Oxford in the 1850s and became life-long friends, collaborators, and business partners. They shared a love of art, all things medieval, and poetry. It is fitting, therefore, that their final project together was the Kelmscott Chaucer, as they had both adored the writer since their time at Oxford. Morris had first mentioned the Chaucer to colleagues in 1891, and it was formally announced in 1892 that the edition was forthcoming. The volume was an enormous undertaking, and progress was slow, as solutions had to be found for transferring Burne-Jones’s illustrations effectively and efficiently onto wood blocks for engraving. However, Burne-Jones was confident in the work they were doing, writing, “if we live to finish it, it will be like a pocket cathedral – so full of design and I think Morris the greatest master of ornament in the world.”

Both Morris and Burne-Jones lived to finish it, and the Kelmscott Chaucer was published on June 26, 1896. The power of the Kelmscott Chaucer is in how all the elements harmonise to create something visually spectacular. There is a profound sense of balance between the typography (Troy and Chaucer type) with the frames and borders which encase Burne-Jones’s distinctive illustrations. With the Kelmscott Chaucer, Morris had effectively achieved his aim of creating his ideal book by demonstrating, in an extraordinary way, that ‘A book ornamented with pictures that are suitable for that book, and that book only, may become a work of art second to none’.

Morris died on October 3, 1896, just four months after the publication of the Kelmscott Chaucer. His friends, Emery Walker and Sydney Cockerell, oversaw the remaining eleven books that Morris had planned to publish before deciding to close the Press. The final book they published was, appropriately, A Note by William Morris on His Aims in Founding the Kelmscott Press in 1898. In it, Morris writes: “It was the essence of my undertaking to produce books which it would be a pleasure to look upon as pieces of printing and arrangement of type.” With the Kelmscott Press, then, Morris had turned the book into an art object, an aesthetic artefact. By applying his design philosophy and standards to book production, Morris gave us permission to look at books as well as to read them.

Dr. Michael John Goodman is a Welsh writer and educator. As well as writing about book history and design, he also makes Victorian illustration accessible and interesting to new audiences. He is the creator of the open-access resources The Victorian Illustrated Shakespeare Archive, The Charles Dickens Illustrated Gallery, and The Kelmscott Chaucer Online. He has published widely in academic journals and books, and his projects have featured in The Washington Post, The Guardian and the BBC.

Images courtesy Kelmscott Chaucer Online, public domain.

The post William Morris and the Ideal Book appeared first on PRINT Magazine.